This initiative is saving students millions of dollars in textbook costs

At MSU Denver, Open Educational Resources are improving accessibility while offering greater flexibility to instructors.

It’s an unhappy bump on the road to earning a college degree: At the start of each semester, students must dig deep into their pockets to buy pricey textbooks that instructors have assigned for their courses.

But at Metropolitan State University of Denver, adoption of Open Educational Resources — books, videos and other instructional materials that can be downloaded, edited and shared for free — is growing. OER helps alleviate the financial strain on students, saving them $3.7 million since a cross-campus initiative was launched five years ago.

The ultimate goal is to move toward degrees that have zero cost for textbooks, said Emily Ragan, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry who heads the University’s OER task force.

Affordability is a key consideration for MSU Denver students, many of whom work multiple jobs while seeking a college degree, she said. OER fits nicely with the University’s mission to make education more accessible, Ragan added.

“It removes a cost barrier,” she said. “Some students have to either work more hours or take out more informal loans to pay for the cost of course materials. That’s something that many students didn’t fully comprehend they would be on the hook for before they started college.”

The OER movement in American higher education started taking shape nearly a quarter-century ago. The practice gained momentum in Colorado in 2018 when the state started offering grants to public institutions of higher education, including MSU Denver, to support the adoption of OER in the classroom.

“We’ve been able to offer cash incentives to faculty to learn about OER and to adopt OER into their classes,” Ragan said. “That’s been a game-changer. We’ve seen really dramatic growth. It’s been helped in large part by the state grants.”

RELATED: The death of textbooks?

OER materials come in assorted shapes and sizes that can fit a variety of needs.

One example is OpenStax textbooks, published by Rice University with substantial philanthropic support. They mimic the conventional model of peer-reviewed academic publishing, Ragan said. She added that Rice spends about half a million dollars on each book it develops.

Many Open Educational Resources are published under Creative Commons licenses that allow faculty members to modify the content, affording them a greater degree of creativity in designing their courses, Ragan said.

“I think that is the way faculty members like to operate,” she said. “Having a Creative Commons license provides a lot of collaboration and iteration, and we can customize resources to work well with our student body here.”

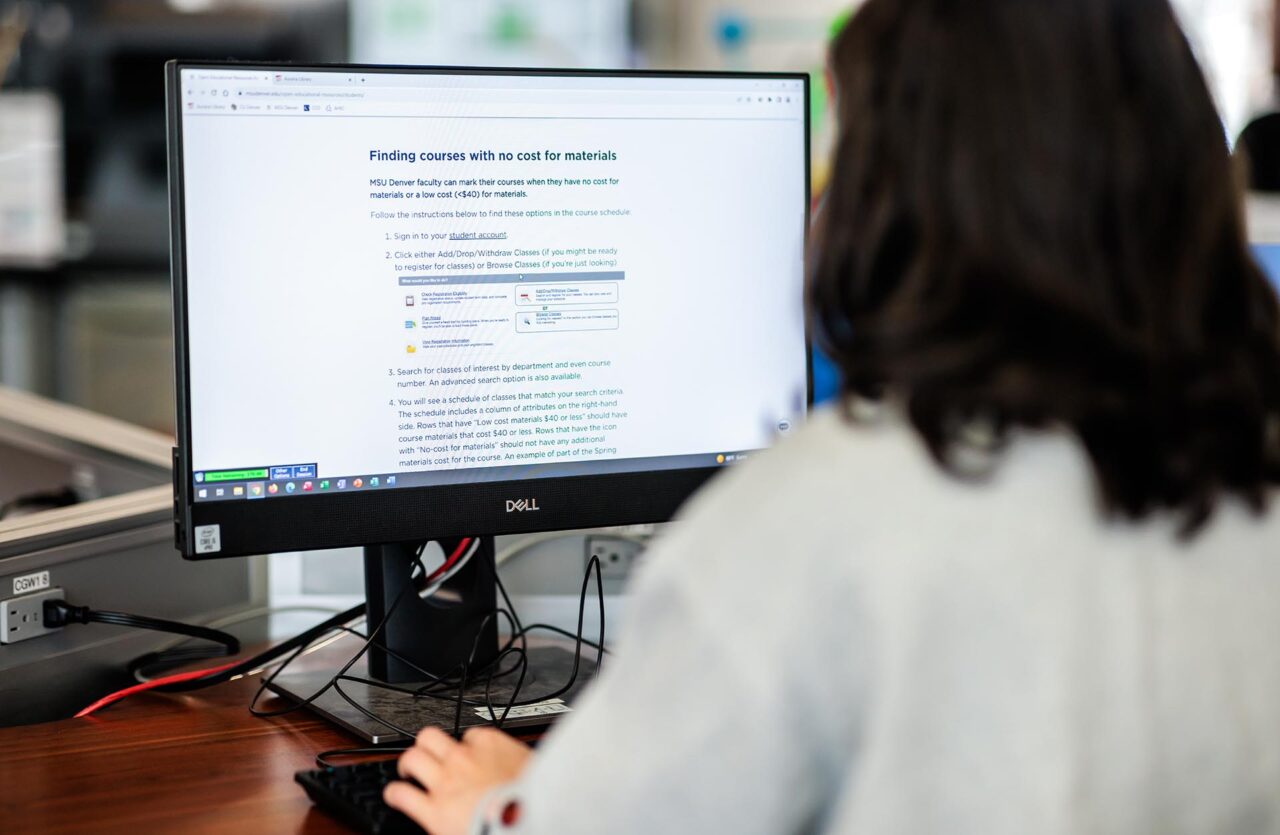

With the cost of textbooks averaging students $339-600 per academic year, MSU Denver updated its course listings, allowing faculty members to indicate in their descriptions whether materials will be no-cost or low-cost. “We’re focusing on the cost to the students for materials,” Ragan said. “We thought that’s what students care about on a practical level.”

Abrianna Mangiamele, a third-year MSU Denver student majoring in Public Relations, works as a student intern for the OER task force. She voices a complaint many students have about paying out of pocket for course materials: “I’ve had classes where they say, ‘Buy this textbook,’ but I get to class and then they say, ‘We’re not going to really use it.’”

She credits Louanne Saraga-Walters, affiliate faculty member in Journalism and Media Production, who has taught several of her PR classes, with creatively adopting OER for her students. Saraga-Walters shares articles, YouTube videos, blog links and selected textbook excerpts.

“I can read two articles and watch a five-minute video,” Mangiamele said. “A lot of times, I think I can get more out of that than reading a textbook.”

Mangiamele has been working on a PR plan on behalf of the OER task force to raise awareness of the materials among students and faculty alike.

“Last semester, we realized that students don’t really know what it (OER) is at all,” she said. “They interviewed students to ask what it is that is holding them back (from enrolling). Most of them said they would choose not to take a class if they knew a textbook would be a certain price.”

RELATED: A catalyzing force for open access

Sanaa Riaz, Ph.D., a cultural anthropologist and associate professor in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, said she was skeptical about whether OER would work in her classes.

“When I started, I didn’t think OER textbooks were that high-quality,” she said. “I wouldn’t find enough for my courses. I started small, incorporating textbook resources for an introductory course in Anthropology that anyone would need materials for, and then built it on that. Most recently, I’ve been able to build my Religious Narratives and Culture and Middle Eastern Cultures General Studies courses all OER-based.”

Using OER has led her to shift her use of materials in courses, Riaz said. As one example, she pulled questions from a classic work on the economics of cultural heritage and had her students consider cultural-heritage preservation examples from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization website.

“Without actually having them read through another academic piece about the economics of cultural heritage, I was already having them apply it in a discussion,” she said. “The fact that you can think outside the box while using OER is fantastic. That’s how I’ve incrementally become a believer.”

Riaz is convinced that in addition to cost savings, students actively benefit from her creative use of OER in the classroom.

“My students have really enjoyed the OER resources I’ve used,” she said. “It allows me to incorporate all models of instructional delivery, not just focusing on instructor-student, but I’ve been able to create a lot of student-student discussion. I’ve barely explored the tip of the iceberg here.”