‘Ghosts’ on campus: The plight of homeless students

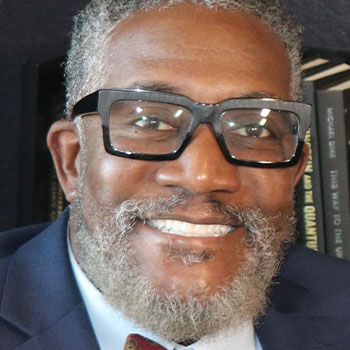

Randi Smith knew there was a hidden population of homeless students on campus – and she was determined to help them.

It’s the end of college classes after a long afternoon.

Students start packing up their stuff and discussing what they’re doing later. A couple are going for coffee, some have homework to do, a small group is going to the movies. None of them realize that one of their peers will be heading down to the food bank hoping to find a meal, then spending the night in a car in the campus parking lot.

“Student homelessness” sounds like a misnomer, two words that the mind doesn’t naturally put together. And in fairness, it is a fairly new phenomenon.

Thirty years ago, less than a quarter of people aged 18 to 24 went to college. But student numbers have almost doubled since then, even as tuition rates have risen sharply. Now, two-thirds of full-time students need help from grants, tax credits or deductions just to get by. And even then, some don’t make it.

Shadow students

Psychology professor Randi Smith long suspected there was a ‘ghost’ population of homeless students at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Anecdotal evidence kept mounting up. Campus security reported blanketed figures hunkered down in cars in the parking lot. The University’s food bank was very well used. Occasionally, Smith’s own students would confide they had nowhere to stay.

Personally, it really bothered her. But as a psychologist, she recognized how difficult it might be to identify, let alone help, this group hiding in plain sight before her.

“Understandably, homeless students tend to hide their status not just from fellow students but from professors, too,” she said. “There’s a lot of shame associated with being homeless, along with some pretty ugly stereotypes.”

While there has been previous research focusing on college students and homelessness, most of it came from support service professionals or well-meaning volunteers. Such studies had a slight petri-dish quality – they were about homeless students rather than coming from their own experiences.

Diverse groups

So in 2014, professor Smith took matters into her own hands.

She sent an email to 20,000 students enquiring about their past-and-current living status. Soon, she got 187 replies from students identifying themselves as homeless – and 160 of them went on to complete a survey she’d prepared.

“The survey results showed a high representation of the LGBT community, veterans, parents with dependent children, caregivers and people with disabling physical or psychiatric conditions,” Smith said.

“It wasn’t really a surprise to find that our respondents came from very diverse and older groups. Homeless students tend not to be your ‘traditional’ 20-year-old college students.”

Hard times

The findings painted a stark view of hard lives. The majority had spent between one and seven months homeless. The most common reason for becoming homeless (53 percent) was simply being unable to make the rent. And while 62 percent had couch-surfed at friends’ homes, almost a quarter had spent time living on the streets.

There were grueling details. 37 percent of respondents had been asked to exchange sex for money, food, shelter, drugs or clothing. Heartbreakingly, 19 percent had.

Nineteen percent had been violently attacked. (A particularly galling fact given that 24 percent of the study group initially became homeless after fleeing violence at home.) Over half had visited an emergency room. And underscoring the group’s overall vulnerability, 13 percent had been hospitalized for a mental health condition.

Against the odds

And yet, as Smith pointed out, all these people were still at college. “It’s truly amazing how these students keep their minds on long-term academic goals while facing the grinding pressures that homelessness and hunger create.”

Smith recently met a student who, forced from her home while pregnant at 15, spent the next 10 years living in shelters – and sometimes on the street – with her children. But never stopped her schooling.

“Despite overwhelming odds,” Smith said, “she was certain that education was the way to break the cycle. Now she’s a student at MSU Denver and works full time, but remains undaunted. People who’ve experienced homelessness learn how to be scrappy; they persevere through circumstances that might knock the rest of us off our feet.”

Caring campus

Still, it helps that MSU Denver offers assistance. Following the study, new services and outreach procedures were created to meet the needs of this fragile population.

“We now have some great collaborative relationships with community organizations to address housing needs,” Smith explained, “Plus there are mental health services and an excellent CARE team that helps struggling students find services to stay enrolled in school.”

And the campus food bank? “It’s been relocated to a more visible location and its hours extended to better serve hungry students.”

Affordable homes

Last year, Smith carried out a follow-up study. The initial findings have shown that homelessness continues among MSU Denver students, but she is confident the new measures will have a positive future impact.

And as for long-term goals? “First, I’d like everyone on campus to be aware that there’s a largely invisible group of students doing their homework in cars, shelters and even under bridges,” Smith said. “Second, I’d like our hungry and homeless students to know they are not alone.

“And finally, I want to highlight the urgent need for affordable housing in the Denver metro area. Ultimately, our City Council, mayor and private industry sector will have to address the ever-declining availability of affordable living spaces.”

Still surprising

While a lot has changed for the better since professor Smith first had her big idea four years ago, one thing remains constant – she is still consistently surprised by the students she champions.

“As a scientist, I can sometimes get caught up in the numbers and the demographics,” she said. “But then I’ll meet with the students themselves and hear their inspiring stories, and the numbers become a secondary concern. Every story I hear is incredibly powerful and moving.

“This whole project has been a very humbling experience.”