Can AI help save Colorado’s rivers?

A professor is using sustainable systems engineering to learn the technology’s potential to help ease droughts.

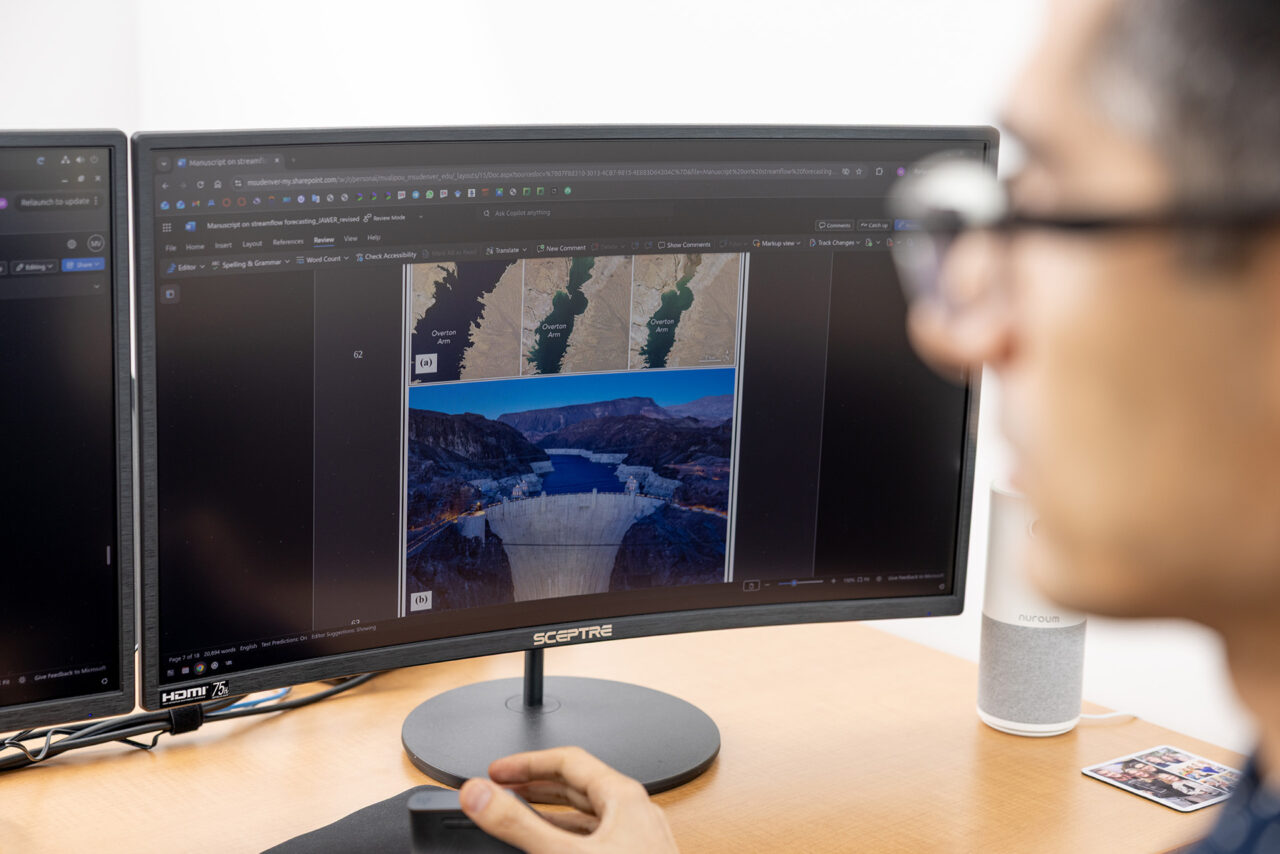

The Colorado River Basin is enduring one of the longest and most severe droughts in modern history. The river, vital to 40 million people across seven states and parts of Mexico, is rapidly drying. Yet Colorado still lacks a reliable system for forecasting streamflow, leaving communities vulnerable to sudden shortages.

That’s where Mohammad Valipour, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Engineering and Engineering Technology at Metropolitan State University of Denver, is stepping in. In 2023, Valipour received a grant from the Colorado Water Conservation Board to develop an AI system that forecasts streamflow across Colorado’s seven major rivers. The goal: give communities weeks, or even months, of advance warning about drought.

“We can’t stop droughts from happening,” Valipour said. “But we can give communities time. Time to plan, time to react and time to prevent the worst impacts.”

RELATED: ‘We are living in a tinderbox’

Across the country, artificial intelligence is sparking intense debate, especially around water use. Cooling systems for large data centers can demand up to 5 million gallons of water per day, a particularly stark figure in regions already stressed by drought. Colorado and the surrounding Colorado River Basin have been in a “megadrought” since 2000, the longest in more than two decades. While parts of the state briefly escaped drought in mid-2023, much of Colorado is once again parched, making water management more urgent than ever.

Valipour’s work tracks the rivers themselves, rather than focusing solely on underground water or soil moisture. He’s analyzed more than 30 years of data, including U.S. Geological Survey streamflow records, precipitation measurements from NASA’s Tropical Rainfall Measuring and Global Precipitation Measurement satellites, and snowpack data from the Airborne Snow Observatory. Satellite data has proven particularly valuable in regions with few ground sensors, filling gaps and giving researchers a more complete picture of Colorado’s waterways.

Synthesizing this enormous volume of information requires serious computing power. “Handling all this data on a normal computer would take weeks to produce a single forecast,” Valipour said. “A custom-built supercomputer optimized for running advanced AI model lets us process decades of records in hours, turning mountains of information into actionable predictions.”

Once the data is processed, advanced AI models help make sense of it. Valipour used two hybrid neural network models designed to untangle complex patterns. One model separates short-term changes, such as sudden rainfall, from long-term trends, such as declining groundwater, and “remembers” how these patterns affected rivers in the past. The other model builds on this by spotting repeating short-term cycles, such as seasonal dry spells, and combining them with long-term trends. Together, these models forecast daily and monthly river flow.

“Traditional models struggle to capture the complexity of Colorado’s rivers,” Valipour said. “Hybrid neural network models reveal patterns in decades of streamflow, precipitation and snowpack data that humans alone could never detect.” By analyzing past patterns, the system can identify and flag early signs of drought, giving communities and farmers the information they need to act before problems become critical.

RELATED: Sustainability Hub takes root at MSU Denver

Valipour is rigorously testing and refining the models, determining when and where they perform best. The insights will guide research and help water managers, reservoir operators and policymakers make informed decisions to protect people, agriculture and ecosystems.

When AI’s environmental footprint is under scrutiny, this work offers a different perspective. Yes, data centers and AI infrastructure can consume large amounts of water and energy, and those concerns are valid. But AI can also be part of the solution.

“AI isn’t inherently good or bad,” Valipour said. “It depends on how we use it. In this case, we’re using it to save water, not waste it.”

In a hotter, drier future, tools that reveal the early signs of drought could make all the difference. “In an ideal world, our next steps include expanding the system statewide and using these forecasts to develop localized drought alarm systems,” Valipour said. “These alarms could tell communities and farmers exactly when they’re at risk, helping them adjust irrigation, planting patterns and water use before shortages become critical and threaten the sustainability of our future.”

Learn more about Engineering and Engineering Technology programs at MSU Denver.