These insects are vampires and cannibals

New video footage reveals how mosquito larvae capture their prey: other mosquito larvae.

We all know that mosquitoes drink blood. What you may not know is that some mosquito larvae are also cannibals.

Before becoming adults, mosquito larvae live in lakes, ponds, rivers, streams and even neighborhood gardens. While most mosquito larvae feed on algae and bacteria, some feed on other aquatic insects — including other mosquito larvae.

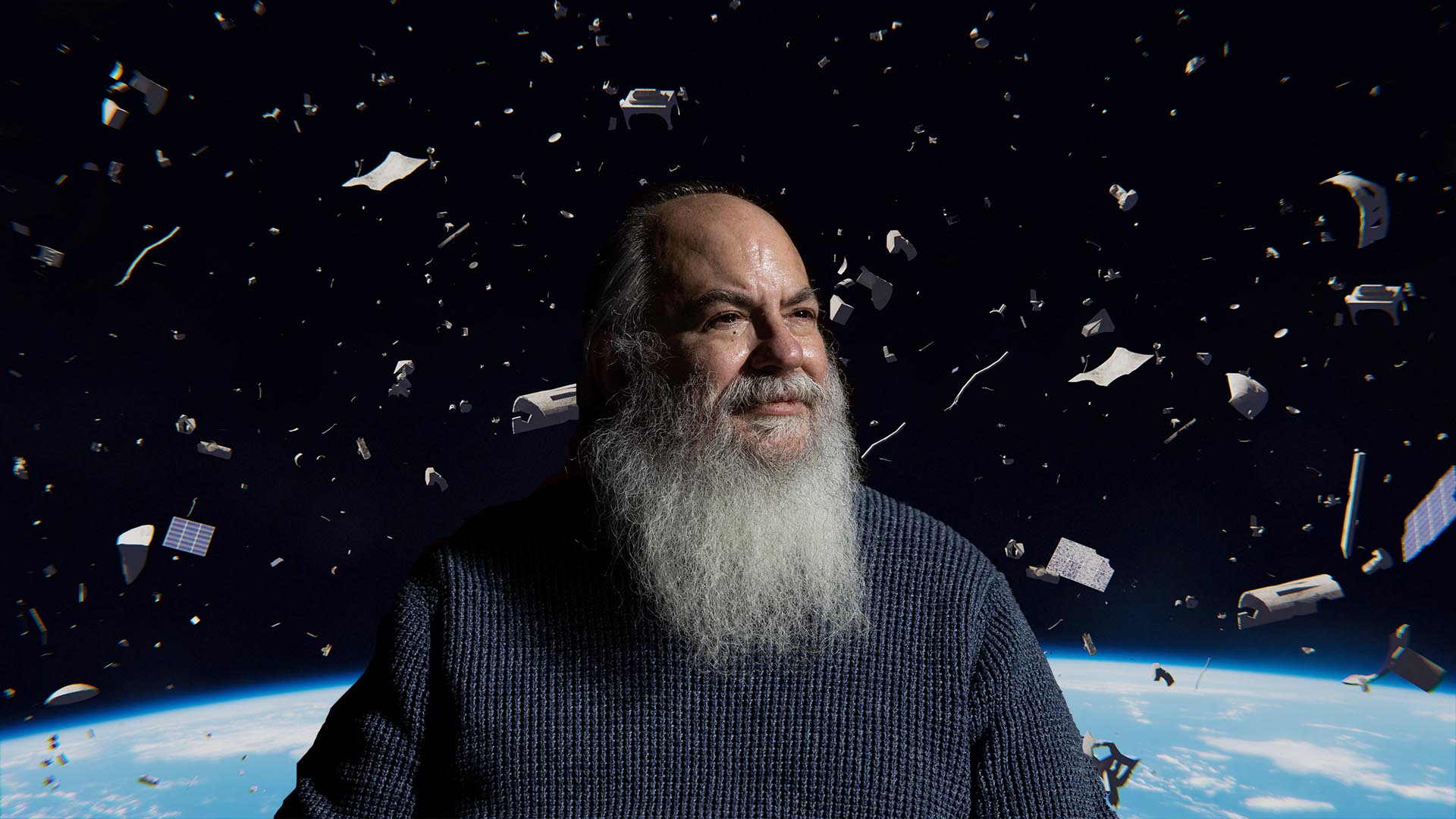

Robert G. Hancock, Ph.D., professor in the Department of Biology at Metropolitan State University of Denver, first observed mosquito larvae attacking other larvae under a microscope in a graduate course in the 1980s.

“It was so incredibly fast,” he said in a news release. “The only thing that we saw was a blur of action.”

Since that graduate course, advances in video and microscope technology have allowed Hancock and his students to observe mosquitoes in extreme slow motion. His groundbreaking research, published in the Annals of the Entomological Society of America, shows not just that they eat other larvae but how.

RELATED: What’s behind Colorado’s West Nile virus surge?

Hancock’s report includes 10 videos of larvae from three species of mosquito. The Toxorhynchites amboinensis and Psorophora ciliata species’ diets rely on consuming other insect larvae. The Sabethes cyaneus species eats microorganisms and sometimes other larvae.

The Toxorhynchites and Psorophora larvae strike prey by elongating their necks, almost completely removing their heads from their bodies. Then, they grab the prey and snap their mandibles closed.

Hancock recalls his surprise when he and his researchers first successfully recorded the strike on film. “I saw it first,” he said, “and my jaw dropped. And it still does every time I watch it.”

Sabethes mosquito larvae use their long tails to sweep prey toward their heads, then open their mandibles and maxillae (pincerlike mouth parts) and snap onto the prey.

The larvae’s use of the tail was also a surprise, Hancock said.

Both striking mechanisms take about 15 milliseconds. That speed indicates an almost-reflexive behavior called a fixed-action pattern, Hancock said. He compared it with the action of swallowing, which involves multiple muscular movements that work together in the blink of an eye. “All of this stuff has to work in concert — we all do it so automatically,” he said. “And that’s exactly what these (mosquito-larvae strikes) have to be. It’s a package deal.”

Toxorhynchites and Psorophora mosquitoes are well-known for their predatory characteristics. The Toxorhynchites species has been studied as a potential tool for controlling mosquitoes that carry germs because it preys on the Aedes species, which spreads zoonotic diseases such as Zika. Because a single Toxorhynchites larva could consume up to 5,000 larvae before maturing into adulthood, adult Toxorhynchites mosquitoes are some of the largest in the world, as are Psorophora.

Hancock recorded the strikes in 2020 with students at MSU Denver using a high-speed digital camera that captures more than 4,000 frames per second. The lights needed to view the larvae under the microscope were so bright and hot that they had to use protective filters “to not just cook” the larvae, he said. They also wore dark sunglasses to protect the researchers’ eyes.

Hancock has studied mosquitoes for most of his career and says this new research can help unveil the mysteries of nature, especially in aquatic species. The videos could open people’s eyes to the species living in even the smallest pools of water. “Small containers of water that don’t move are primarily the domain of mosquitoes,” he said.