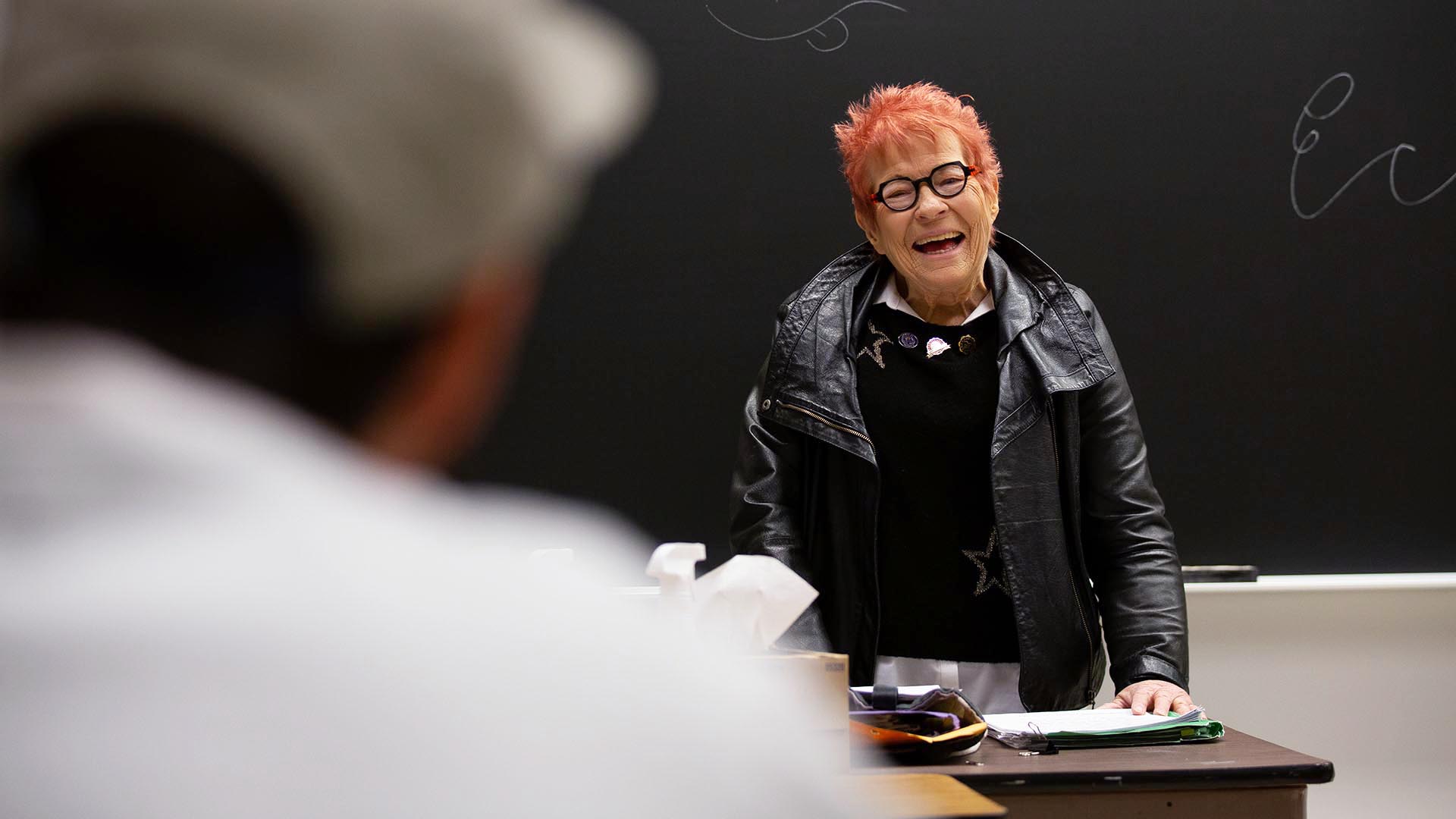

Sandra Doe: teacher, survivor, writer

One of MSU Denver’s original Roadrunners retires after a 57-year career.

Sandra Doe, Ed.D., has seen it all. As one of the first 35 hires in 1965 at what was then called Metropolitan State College, she remembers what it was like being an original Roadrunner. Then, the Auraria Campus was just a group of rented buildings scattered across downtown Denver with students and faculty members running from building to building to get to class on time.

Now an English professor, Doe has taught more than 10,000 students since then, as the school became Metro State and then Metropolitan State University of Denver. She recalls a student who survived the Vietnam War and would duck at the sound of a car backfiring as a result of post-traumatic stress disorder. She elicited an essay from a student who survived the Bataan Death March in World War II. Today, she’s had students with family members and friends who have been directly affected by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

“Everyone comes with a life and a story,” Doe said. “And they write them if I can coach the stories out of them. And they’re wonderful stories.”

Doe has long had a deep love for writing, dating back to high school. At Denver South High School, she was on the staff of a literary magazine called Folio Leaves and then decided to major in English while in college.

“(Writing) was the only thing I could ever do,” she said.

While Doe was on sabbatical leave in California, her sister had her write affirmations: “I am a promising young poet.” “I am a writer.”

“Now, I am a poet and a writer, and the affirmations came true,” Doe said. “And I appreciate very much having a twirl of pen, being able to do it and teaching other people to do it.”

Social advocate

Doe has lived in Denver long enough to consider herself a Colorado native. She moved to the city when she was 5 years old and eventually graduated from Denver South, one of the four original high schools in Denver. After receiving her bachelor’s degree in English from Doane University, she thought the brand-new Metropolitan State College would be a great place to help make ends meet while working on her master’s degree.

Her time at MSU Denver was often adventurous. Long before the national movements started, Doe was part of an anti-racist, nonsexist improvisational theatre group with students and other faculty members. In a field that used to predominantly employ men, she also protested for hiring more women faculty members.

“We were all flaming feminists,” she recalled. “And we were going to fight about not having enough women faculty members.”

In her decades as a teacher, Doe has seen Denver culture and society significantly shift. While the movement for hiring women faculty members eventually took off, those most recently hired were the first to be fired when the University hit financial exigency.

She also remembers a time when women were afraid to speak out against sexual assault.

“There weren’t as many people speaking out like there are in MeToo,” Doe said. “But now, when I hear people speaking out, I am not surprised. Because all you have to do is be a woman to know that this is a difficult situation.”

Doe also once took part in a street class run by former MSU Denver Professor Charles Angeletti, where she and others spent four nights on the streets to get firsthand experience of and empathy for what people experiencing homelessness go through. Through the exercise, she also learned about resources for the homeless, a disturbing experience that gave her a great appreciation for her life.

With the rise of homeless camps in downtown Denver, Doe has remained passionate about solving the problem.

“If we could do something for the homeless, that would be very important because it’s mushroomed,” Doe said. “It’s large, and it’s everywhere, and it’s disheartening and hurts your heart.”

California/Iowa adventure

In 1975, Doe had been teaching for about 10 years when she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

“I thought I was going to die,” she said.

Confronted with mortality, Doe set off on an adventure with those closest to her. She went on sabbatical leave with her sister and two young children and transferred her chemotherapy to California, land of personal-growth therapy. She lived in Berkeley and went to San Francisco to walk across hot coals and have a rebirthing session in a hot tub.

“That was an adventure,” she said.

While in Berkeley, Doe researched the works of her late, great uncle, artist Ray Boynton, and decided to become an author. But six months into her research, her sabbatical had ended and she needed more time, so she taught at San Francisco State University to make ends meet until she was ready to come home.

Before returning to MSU Denver for good, Doe set off to complete a fellowship with The Institute on Writing, a joint project of the University of Iowa and the National Endowment for the Humanities, to develop a first-year composition program, so she could bring it back and teach the curriculum to other faculty members. Doe was an English teacher to pay the bills, but poetry was always her love.

“I went under the flag of composition, but in my heart I was a poet,” Doe said. “It was a passionate time, and I wrote passionate things. And now I couldn’t possibly think about publishing them, and I wish I’d worked harder at it, but I didn’t. I worked hard at teaching students.”

While at Iowa — “the great mecca of writing,” she said — she discovered the University’s writing center, and she knew she had to bring the idea back to MSU Denver.

Developing the Writing Center at MSU Denver wasn’t easy. At first, the Colorado Commission on Higher Education thought the center was a remedial program and resisted. Doe argued that “writing is a community activity.”

“You need a lot of people listening and putting in input and then getting input and then adjusting and then giving out more input,” she said.

Ultimately, Doe won out, and the Writing Center is still going strong today.

A poem for your travels

After receiving her doctoral degree from the University of Northern Colorado, Doe realized she wanted to write a book before she died. With all the material she gathered in California, she began working on a biography of Boynton. Doe is still working on the biography, with just a few chapters to go.

In 1999, Holly House published her first poetry chapbook, “Lies and Promises.” She’s also published collections of poems written by Doe and her students, including “Silver Edge,” “Poems From an Ethnic Festival” and “A Thousand Ways to Kneel and Kiss the Earth: Poems on Gas Fracking.” She self-published “Trip and Return” in 2017, which was written about her first 50 years at MSU Denver.

“I was in a hurry,” Doe said. “If you send a poem into a magazine, it takes them a couple of months, maybe a couple of years, to get back to you as to whether or not they will take it. And I’m not so much interested in that.”

In 2021, she edited and contributed to “Away to Santa Fe: A Collection of Santa Fe Trail Poems,” an ode to her long involvement with the historic Santa Fe Trail Association.

RELATED: 7 must-see Colorado literary landmarks

Her poetic travels aren’t limited to the Southwest, as she’s also experienced Egypt, Great Britain, Costa Rica, Denmark, Germany, France, Peru, India and the Czech Republic.

Her love for traveling and writing has also made her a firm believer in combating climate change. She belongs to several conservancy organizations and wants to be even more active now that she’s retiring.

“We have to save the environment,” Doe said. “We have no planet if we don’t have an environment. There’s only one Earth.”

As a climate-change activist, an empath for people experiencing homelessness and a fighter against racism and sexism, Doe understands what it feels like to be bogged down by the weight of trying to fix everything. Her best advice for young activists is to “attend your own garden.”

“I figured the best thing I can do is be an example and work on my own stuff and try to do my own stuff more successfully,” Doe said.

Now that Doe has taught her final class, her plans for retirement are a work in progress, other than her determination to finish her book about Boynton. The only chapters left to write are about the artist’s retirement and death, but she doesn’t plan on following in those footsteps.

“First you retire, and then you die,” Doe said. “What a scenario. You think people are going through this with open arms, saying, ‘I love retirement!’

“Well, I have an intention to stay here quite a while. I can finish that book, finish that chapter, do something with (Boynton’s) paintings and send the papers to Berkeley. Just let it all go.

“And then I’ll see what’s next. Besides that, you should write a poem a day anyway.”