Q&A: The legacy and impact of Black women judges in the U.S.

Africana Studies Professor Jacqueline McLeod sheds light on why Ketanji Brown Jackson’s Supreme Court nomination matters.

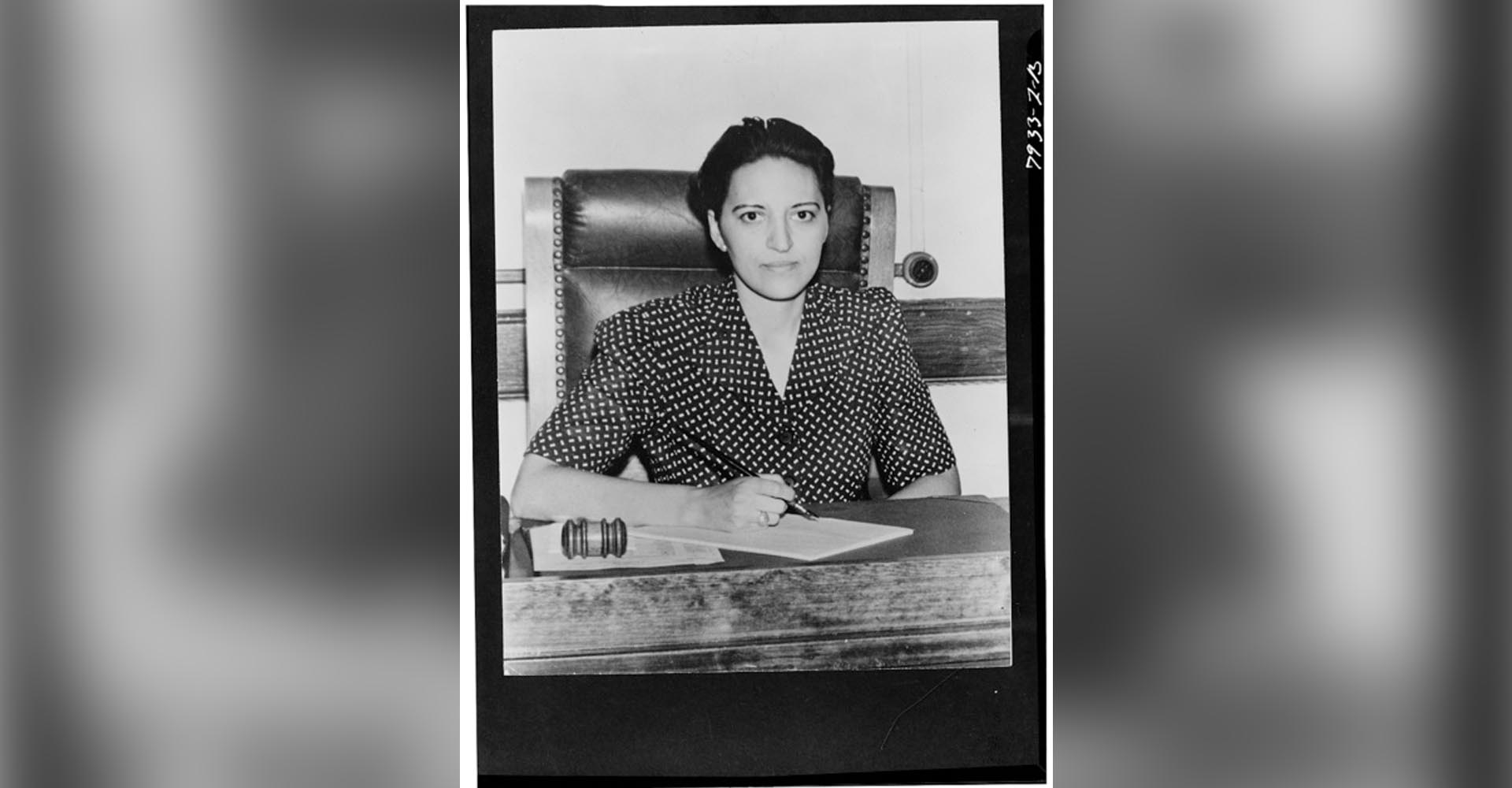

New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed the first Black woman judge in the U.S., Jane Bolin, in 1939. It would take another 27 years for a federal court to appoint its first Black woman, Constance Baker Motley, in 1966. Fifty-six years later, in 2022, President Joe Biden has nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson to the Supreme Court. If confirmed, Brown Jackson would be the first Black woman in U.S. history to serve on the nation’s highest court.

To learn more about the historic significance of this nomination, the RED newsroom spoke with Jacqueline McLeod, Ph.D., Metropolitan State University of Denver professor of Africana Studies and author of “Daughter of the Empire State: The Life of Judge Jane Bolin.”

What was your reaction to the announcement Feb. 25 that Ketanji Brown Jackson was the Supreme Court nominee?

It’s about time. The nomination, and hopefully the confirmation, is most meaningful at this moment in American history because it suggests an appreciation for the necessity of representation in an institution, the court, that interprets the constitutional rights of American citizens. Especially if we are to cultivate a sense of legitimacy, we need to have that kind of representation. And we all know what the state of the society is when I say “this moment in American history.” A time when racial animus is bold and unapologetic. A time when constitutional rights like voting seem to be eroding quickly. When Black Lives Matter has to be a refrain across the country. So in that context, this nomination is very meaningful.

Since Jane Bolin was appointed as the first Black woman judge in 1939, what are some of the milestones that have gotten us to where we are now?

Several milestones within the civil rights movement and within the legal system have brought us to 2022 when a cadre of African American women exists in the legal profession, eligible for election or appointment to any court in the land. The major milestones within the civil-rights movement include: the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Supreme Court ruled in Brown that racial segregation in education is unconstitutional, and over time that increased the number of African Americans enrolled in universities, medical schools and law schools. The 1964 Civil Rights Act outlawed discrimination in public accommodations, including schools, but also Title VII prohibited nondiscrimination based on not just race but also sex in every aspect of employment — from advertisement to separation (being fired). The 1965 Voting Rights Act protected and therefore increased voting among African Americans and allowed them to exercise their choices at the ballot boxes, even though those rights are being eroded as we speak.

Within the legal profession, I would say a major milestone since Jane Bolin’s appointment in 1939 would have to be Constance Baker Motley’s appointment to the federal judiciary in 1966. There are other women who were legal pioneers, but Motley is important because Justice Brown Jackson actually names her as an inspiration and role model. And Motley named Jane Bolin as her role model. The legacy inaugurated by Jane Bolin directly impacted the legacy inaugurated by Constance Baker Motley in 1966. And clearly her legacy has impacted Judge Brown Jackson and what her legacy will be. These three legacies are intertwined.

RELATED: Considering “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Politics”

Some are saying that Brown Jackson’s background as a public defender and vice chair of the U.S. Sentencing Commission represents an ideological shift in the types of judges confirmed. Why is this important?

Diversity of experience and preparation only enhance the process of deliberation. What Jackson brings with her preparation and practice will be a strength. She won’t shift the conservative tilt on the court, but others have argued that her early impact might be in her dissent, and dissent has its role in speaking to the interests of the public (as the late Justice Ginsburg’s stance on the Voting Rights Act has done). Dissent energizes, encourages and further, it legitimizes what you’re fighting for. Brown Jackson’s dissent would be a great contribution in her early years but also her ability to influence her colleagues, either through persuasion or perspective.

Dissent energizes, encourages and further, it legitimizes what you’re fighting for.

Brown Jackson’s confirmation would mark the first time four women would sit together on the court and the first time two Black justices would sit together on the court. How are your MSU Denver students responding to/receiving this news?

My students responded the same as I did: It’s about time. Generationally speaking, they expect more. They’re pleased that there is representation and all that that suggests, but they’re astute enough to know that this physical representation is just the beginning. Real, enduring progress will come only through decisions that truly protect our constitutional rights.

RELATED: Women push to the front