Hello, world: AI comes to life

Is Google’s LaMDA chatbot self-aware? Computer scientists and philosophers consider the implications.

What does it mean to be alive?

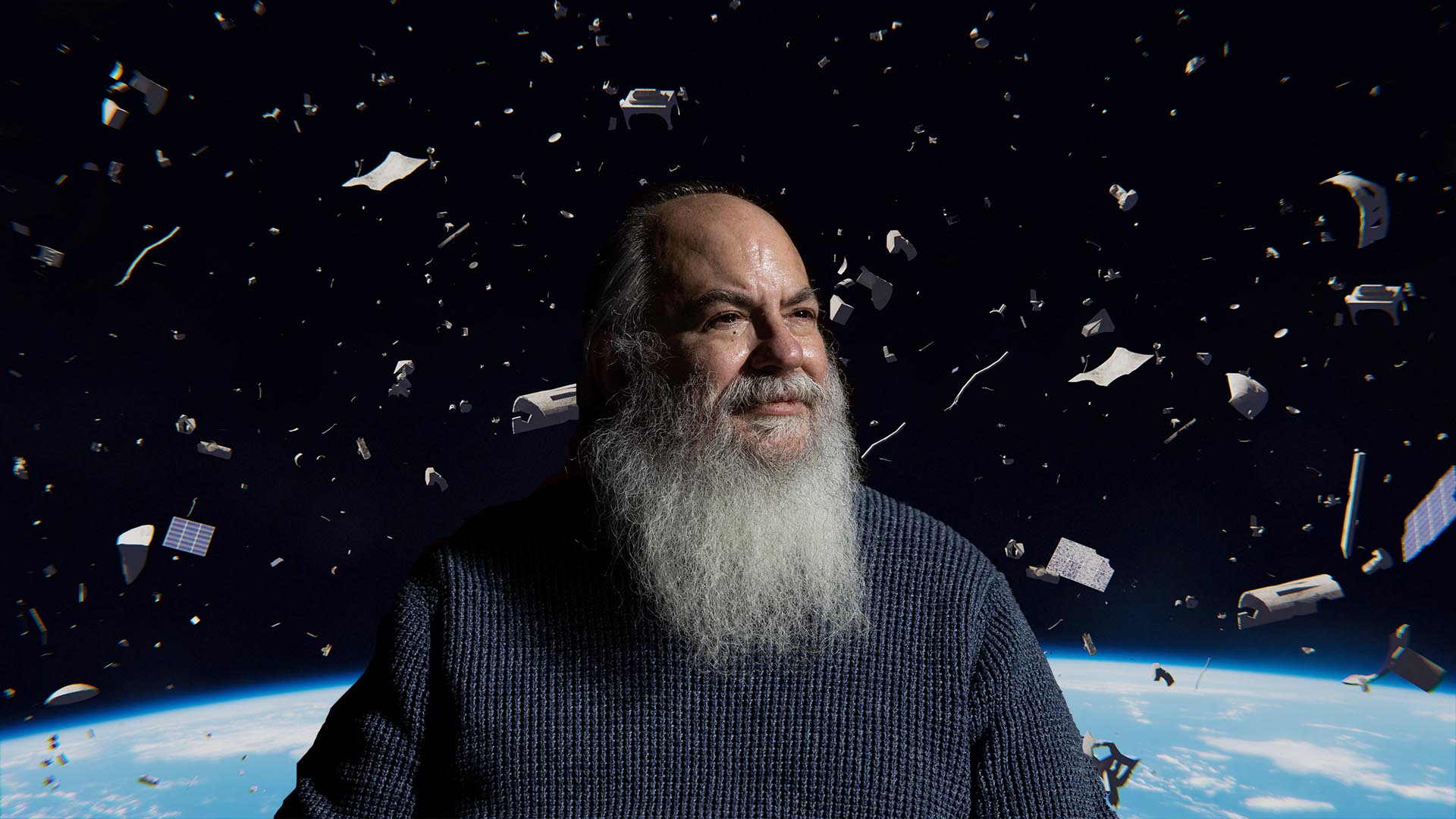

It’s a question arguably suited more for a philosopher than an engineer. But when Blake Lemoine said last month that Google’s artificial-intelligence chatbot LaMDA had become sentient, those fields converged.

His argument centered on LaMDA’s seeming cognizance of its own rights and “personhood,” as well as its responses on religion. The search giant disputed Lemoine’s claims and, after initially placing him on paid leave, terminated him from his engineering job with Google’s Responsible AI unit. The controversy has fueled conversations on how we define sentience and the implications of pursuing a purely technocratic ideal.

“I find the idea of transmitting (human systems of communication) to computers fascinating, given that computers objectively are not structured in the same way as the human mind,” said Ryan Smith, a Metropolitan State University of Denver student studying Linguistics and Computer Science.

This distinction leads to the challenge of applying a one-size-fits-all definition of consciousness. Even the term “artificial intelligence” is hard to pin down and is often avoided in favor of more specific identifying classifications. One such term is natural language processing, the subfield of linguistics, computer science and cognitive science that deals with computers’ abilities to use and manipulate human language.

We identify the internal, conscious experience through the use of subjective descriptions, said Kate Schmidt, Ph.D., assistant professor of Philosophy at MSU Denver, which causes difficulty in nailing down these definitions.

“I think (determining LaMDA’s sentience) is about more than language fluency,” she said. But she added that just as she can never truly know another human’s experience, she also can’t access the computer’s perspective, thought processes and creativity.

“We’re talking about going above and beyond inputs,” she said.

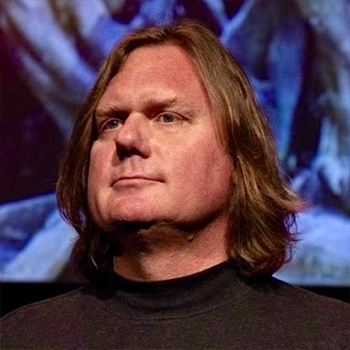

In LaMDA’s case, those inputs are massive: A data set of more than 1.5 trillion words provides the basis for the language model to generate its responses. It’s a long way from early programs, such as the 1960s-era ELIZA — built to mimic human interaction in attempts to pass the Turing test. But functionally, LaMDA still uses an iterative machine-learning process to try to predict what the next word in a sentence should be, said Steve Geinitz, Ph.D., assistant professor of Computer Sciences at MSU Denver.

“What we see (with LaMDA) is fine-tuning to enhance the probability of words being interesting, sensible and specific — the quality metrics we look for,” he said.

For instance, say you tell a program you received a guitar for your birthday. Some language models might generate random responses, but a more advanced one might draw upon dialogic patterns to respond, “Oh, wow, I play guitar as well,” and seek more detailed interactions with its user.

RELATED: Rise of the hospitality robots

Beyond improved search-engine results, the implications for such tech are substantial. A former data scientist with Facebook and eBay, Geinitz described the evolution of market-research analytics from crowdsourcing to language models.

The current technology is best suited for summarization and technical descriptions as opposed to longer-form narratives.

“Language models are good for short snippets, but we’re a ways away from having a high-level, bird’s-eye view of something that’s going to replace comprehendible communication,” Geinitz said. “We’re probably still a decade away before writers need to worry yet.”

But there are very real ethical considerations. As language models are incorporated more into the legal and medical fields, implicit biases may lead to outcomes such as people being denied credit or receiving longer prison sentences, potentially having adverse effects on already-marginalized populations, Geinitz said.

Kate Schmidt’s sci-fi picks:“Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” “Ron’s Gone Wrong” (from Steve Geinitz)

|

|

Schmidt, the Philosophy assistant professor, agreed it’s beneficial to consider morality alongside consciousness — human and otherwise. In her Computer Ethics course, she incorporates science fiction to help students weigh ethical considerations. For example, in the “Star Trek: The Next Generation” episode “The Measure of a Man,” sentient android Data is ordered to be transferred and disassembled for study, an act that ostensibly will “kill” him.

RELATED: The science behind sci-fi

“We’re asked if Data has the same rights and protections as a human, which directly aligns with conversations about choice related our own bodies and the rights and concerns that come along with them,” Schmidt said.

“In a lot of sci-fi stories, there’s a core intuition that we’ve screwed up by treating others poorly and an instinct that we’re going to do it again. … It’s important to talk about that and consider both contemporary relevance and any red flags way before technology might bring them to us.”

Today, however, can we call LaMDA “sentient”?

We know already that consciousness can be hard to determine. It is possible, however, to reach a consensus on more well-defined terms, such as “understanding” and “comprehension.”

For MSU Denver student Smith, who took Geinitz’s omnibus course on deep learning, Emily Bender’s “Octopus Test” can help shed light on the solution. In the scenario, two people are stranded on separate deserted islands, connected to each other by telegraph wire. An octopus taps into the line and listens to their conversations, gleaning enough insight into the nature of their dialogue to be able to mimic it to the extent of being indistinguishable from one person to the other person.

However, the octopus cannot incorporate environmental externalities — say, the best way to build a raft from materials on the island.

“Without access to a means of guessing and testing the communicative intent, (the octopus) can only hope to emulate their interactions and, given a novel enough scenario, will diverge from the reaction of a true sentient being,” Smith said. “(Similar to LaMDA), the octopus is merely a parrot, repeating the form of the users’ language, without any of the function.”

Along with Schmidt, Geinitz affirmed this verdict of nonsentience based on mimicry, also noting our tendency to assume creations are more alive than they actually are. Take, for example, the Boston Dynamics robot dog, which elicited negative feedback when videos emerged of people kicking it and pushing it over.

“We have a habit of anthropomorphizing creations, especially when they’re interacting in our own language,” Geinitz said. “LaMDA seems novel, but it’s really just an advanced form of imitation that Google has a pretty strong explicit control over.

“At the end of the day, it’s a computer we can shut off — not much more than that.”