Fiona Hill: Putin distorting history

Foreign-policy expert says avoiding direct military engagement and pushing non-NATO members to apply diplomatic pressure are crucial strategies in stopping Russia.

An estimated 24 million soldiers and citizens of the Soviet Union died during World War II, as the bloc suffered more deaths than any country involved in the deadliest war in human history. Among the losses were members of current Russian President Vladimir Putin’s family, including his 1-year-old brother, who died during the German siege of Leningrad.

Eight decades later, Putin is laying siege to Ukrainian cities that were also attacked in previous world wars. Russia’s aggression is disrupting the international order that has been in place since WWII, foreign-policy expert Fiona Hill, Ph.D., said Wednesday at the President’s Speaker Series at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

The event was co-sponsored by MSU Denver and the Hart Center for Public Service and moderated by MSU Denver President Janine Davidson, Ph.D., and Foreign Affairs magazine editor Daniel Kurtz-Phelan.

Hill said Putin’s remarks about the “denazification” of Ukraine are distorting history to achieve his personal goals.

“Vladimir Putin has been on this dizzying odyssey talking about his own history,” she said. “If we don’t know our history, including American history and European history, we fall for it when people in Orwellian fashion try to make use of it. Those who control the interpretations of the past can also have influence in the present, and they try to shape the future.”

Hill stressed the importance of education and studying history to prevent powerful people from creating false narratives of current events. She recounts the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, Romania, where Putin told then-President George W. Bush, “Ukraine is not a country” but was partially Eastern Europe and partially gifted Russian land.

“If we let this happen, we’re setting a precedent for the future,” Hill said. “This is a post-imperial, post-colonial land grab. Any other country that has a military force that it gauges as stronger than its neighbors, is in a territorial dispute, has nuclear weapons … can basically assert itself and force its neighbors into doing anything it wants. We can’t afford to let that happen.”

Pressure from China, non-NATO countries needed

While NATO countries have always stressed that the organization is a defensive alliance, the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia was triggered by humanitarian concerns over ethnic cleansing, not a direct attack on a NATO member. Putin has long worried that NATO could bomb Russia, Hill said, and he has tried to prevent Eastern European countries such as Ukraine from joining the alliance.

“Putin always thinks if you have the capability, you will use it … because that’s what he would do,” she said.

Along with claiming Ukraine as Russian land, Putin hoped to disrupt the NATO alliance with his invasion of Ukraine, as Davidson, a former U.S. Navy undersecretary, explained to RED. Davidson said the opposite has happened and that the 30-member NATO alliance has come together after years of preparing for such an event.

Hill said it’s important for NATO not to get drawn into direct military engagement in Ukraine and to push countries outside of Europe and North America to apply diplomatic pressure on Russia.

“Putin’s trying to goad us into this now. He wants to tell the rest of the world that this is a war with NATO, a war with the United States, and that everyone else should keep out of it,” she said. “We do need to engage all of the people sitting on the fence. Even if they don’t want to be part of the battle, make them part of the diplomacy. That’s why we have to keep pushing the Chinese and everyone else to step up.”

Just days before Russia invaded Ukraine, Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping issued a joint statement in February proclaiming that the relationship between their countries “has no limits.” China, as the largest investor in Ukraine (beyond the European Union as a whole), has made itself responsible for the invasion and needs to be held accountable, Hill said.

RELATED: Russian invasion tests the international order

To force Russia to leave Ukraine, Hill added, the U.S., Ukraine and their allies need international diplomatic pressure to push Putin to the negotiating table and to offer him a “golden bridge” to retreat across.

“If Putin thinks we’re trying to end his regime and topple him rather than focus on ending the war, he will keep on going,” she said. “We have to give him, at least in the short to medium term, some sort of a win, something he can spin out of this, as unpalatable as it might be.”

U.S. politics created space for Putin

When Hill accepted a job advising former President Donald Trump on foreign policy, after serving as an intelligence officer for the previous two administrations, she was naïve in thinking the national-security issues evident in the Russian interference in the 2016 election would rise above domestic politics, she said.

“I did regret that I hadn’t spent the same amount of time fully immersing myself into what was going on in U.S. politics” as she did studying Putin, she said. “When I went to the White House, I went in to try to push back against what the Kremlin operatives had done trying to influence our election in 2016. What I hadn’t realized is how vulnerable we were as a political system.”

RELATED: The future of cyberwar

Hill said Putin’s foremost concerns are national security and uniting the Russian people, albeit by suppressing political opposition, while Trump tried to foster division. There’s a straight line between the Trump administration and where we are now, she said, because Putin thought Americans were too busy fighting among themselves on issues of identity, culture and politics.

“I knew all about the Kremlin,” she said. “I knew all these guys in the KGB and the military intelligence operating around Putin. I knew all about the oligarchs. I had no idea about the equivalents in our own politics. I knew there were political action committees, super PACs, money in our politics — but I didn’t realize it was just as dirty and perhaps less responsible than the Kremlin.”

Federal departments undergo a lot of turnover every time a new president is elected, as appointees fill out the federal government from Cabinet-level positions on down the ranks. This can lead to uneven foreign policy, which was exacerbated during the Trump years by the hollowing out of the State Department from resignations and firings of career diplomats, including the termination of the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine in 2019.

“The people who are tracking all of this don’t get listened to,” Hill said. “Trump had no time for the intelligence, but previous administrations as well were not quite so interested in it.”

President Joe Biden takes Russia very seriously, which Hill credits to his experience on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, as vice president and as someone who co-authored a Foreign Affairs article titled “How to Stand Up to the Kremlin” while he was out of office in 2018.

When asked what advice she would give if she still worked for the government, Hill said that while American foreign policy has traditionally focused on Europe and Asia separately, Russia’s war in Europe with China’s indirect support calls for a more cohesive approach.

Land of opportunity

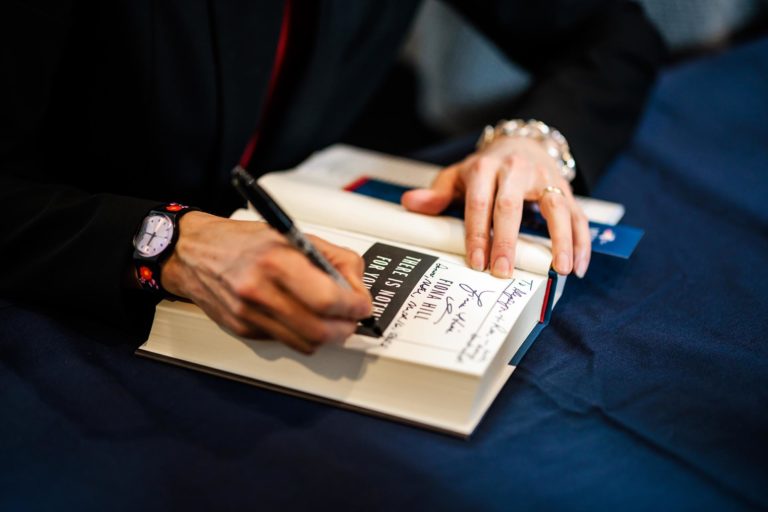

Hill’s trip to Denver was scheduled long before Russia invaded Ukraine. She had planned to discuss her 2021 book “There Is Nothing for You Here,” which shares her journey from a blue-collar “coal house” upbringing in rural England to multiple White House tenures.

She garnered international fame when she weaved her personal story into testimony at the 2019 Trump impeachment trial.

“The biggest story I was trying to tell with the book was how we got to this populist moment in the United States, the 2016 election and the political divisions, which I’d experienced myself growing up in the U.K.,” she said. “(There were) similar stories and socioeconomic grievances, people feeling they lost their identity, because of big shifts in the economy.”

Hill earned a master’s in Soviet studies and a doctorate in history from Harvard University, then went on to study at universities in Scotland and Russia. She said her education wouldn’t have been possible without a host of student grants, fellowships and scholarships from the Rotary Club and the local miners association where she grew up.

“Part of our strength today is investing in people,” she said. “It’s not just an individual act. I couldn’t have done anything without people investing in me. When I got to Harvard, I didn’t have a suit. One of the women lecturers took me out to TJ Maxx and bought me a suit so I wouldn’t be sitting in my ripped jeans and a T-shirt in meetings.”Earlier Wednesday, Hill visited students at the Cybersecurity Center at MSU Denver, which was recently designated by the National Security Agency as a National Center of Academic Excellence in Cyber Defense.

“I know nothing about technical stuff, but I’m trying to learn,” she said. “You realize there is so much out there that you don’t know. Education, learning, acquiring knowledge … you should spend a lifetime doing that. I’m always very heartened by institutions like MSU Denver that give people a chance to come back again.”