What is the color purple?

A co-founder of Black Lives Matter offers 4 steps for action-oriented womanist leadership inspired by Alice Walker.

“Womanism is to feminism as purple is to lavender.”

The quote from poet-activist Alice Walker’s book “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose” shone on the screen behind Melina Abdullah, Ph.D., as she discussed womanism with a packed house Monday at Metropolitan State University of Denver’s CAVEA theater.

Walker introduced the world to womanism, a social theory based on the experiences of black women that holds femininity and culture equally important, in her pioneering 1983 publication. Nearly 40 years later, Abdullah, the University’s 2019 Rachel B. Noel Distinguished Visiting Professor, implored the audience to take an action-oriented approach to womanist leadership.

“We think about the legacy we’re consciously stepping into — of the black women who walked before us,” she said. “And as we examine womanist leadership, it’s not confined to theory. What does it compel us to do?”

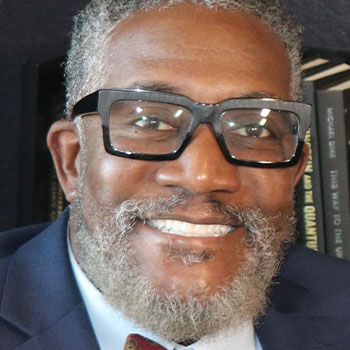

Abdullah is the professor and department chair of Pan-African Studies at California State University, Los Angeles. She’s also a member of the original group organizing the Black Lives Matter movement and currently head of its Los Angeles chapter. In discussing womanism Monday at MSU Denver, she said that looking at a single axis – e.g. gender identity – can obfuscate more complex intersections of systemic oppression that also include factors such as race, class and sexual orientation.

“Purple” is a deeper representation of the whole, just as womanist theory springs from the experiences of African American women and persons-of-color within and distinct from wider – “lavender” – feminist scholarship, Abdullah said, bringing her audience back to Walker’s work.

Purple, proactive

Abdullah explored four interrelated tenets of action-oriented womanist leadership.

First, it must bridge and understand the gap between theory and praxis.

“We can’t get free without envisioning what freedom looks like,” she said.

Likewise, it must take a proactive approach instead of a reactive one.

“Getting caught up in reacting just allows someone else to set their vision and causes us to get caught in the brush fire,” she said.

Abdullah also advocates for group-centered leadership as opposed to a leadership structure driven by the individual.

“The absence of an exalted leader gives everyone the capacity to lead from wherever you are,” she said.

Finally, she said action-oriented womanist leadership must transcend both traditional and non-traditional forms of participation.

“Voting is good, but it’s not enough,” she said.

Further illustrating the complex interplay between social vectors and relative power structures, Abdullah made this timely observation:

“March is Women’s History Month,” she said. “What does that tell us about the implications for the other 11 months of the year?”

Inspiring new approaches

For MSU Denver student Lanie Novack, Abdullah’s view of womanist leadership inspired a new approach for her future profession: high school English teacher.

“I’m always looking out for ways to combat inequality and systemic racism to empower all my students,” she said. “This was awesome insight into that and I can’t wait to learn more.”

Novack attended the event for MSU Denver’s “Educational (In)Equality” course, which examines the historical, cultural and sociological factors forming today’s education landscape.

“When we talk about larger systems of oppression, it’s not just between you and me – it’s at a much bigger scale,” said course instructor Kathryn Young, Ph.D., associate professor of secondary education at MSU Denver.

The timing of Abdullah’s visiting professorship couldn’t have been better for Young, whose class will be further discussing intersecting identities, racism and empowerment in the coming weeks.

“It’s about looking in and looking out,” she said. “What can we do even if we have a limited capacity? If we can’t change the world right away, where are the small places we can we start?”

Abdullah asked the crowd to more personally consider purple, a concept that permeates Walker’s work, including her 1982 novel, “The Color Purple,” which won the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award for its exploration of lives of African American women in 1930s Georgia.

What outside of Walker’s womanist analogy, she asked, are the differences between purple and lavender?

“Purple is a color and lavender is a scent,” offered an attendee from Denver Public Schools’ Noel Community Arts School, a University community partner reflecting the professorship’s namesake.

“That’s a whole different truth you’ve just highlighted,” Abdullah responded. “An oppressive system would say ‘That’s wrong;’ if you would’ve answered that on the SAT, it would’ve been marked wrong – that’s important to think about.”