Summer bites

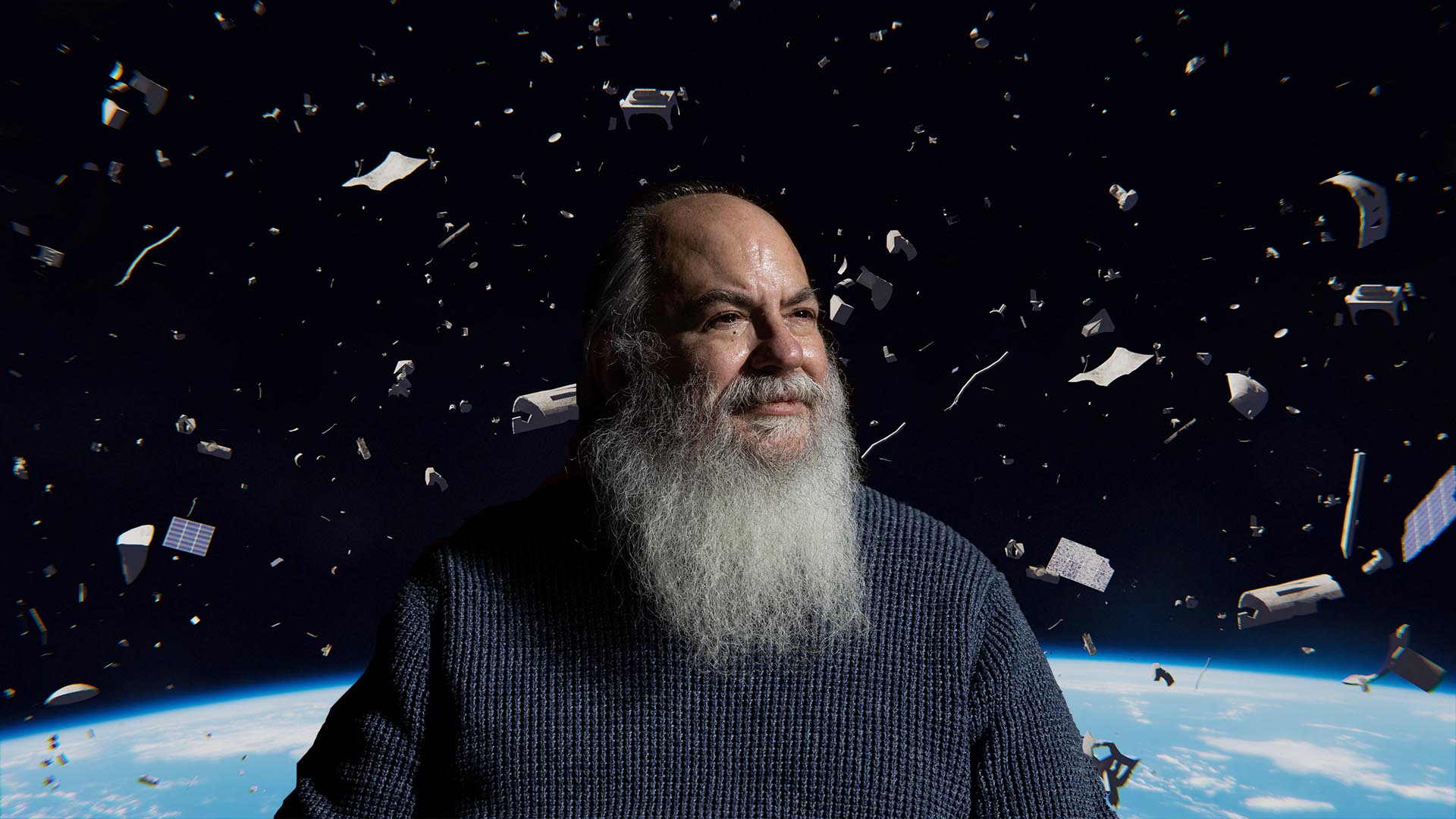

Mosquito season is peaking across Colorado. Here’s what 'Mosquito Man' Bob Hancock wants you to know about the bloodsucking arthropods.

Colorado’s strong snowpack and a wet spring eliminated drought conditions statewide, but that combination may also contribute to a banner season for mosquitoes.

It’s all part of the complicated collections of ecosystems that Coloradans – and 40-plus species of mosquitoes – call home. But with mosquitoes in Pueblo County testing positive for West Nile virus July 25 and mosquitoes in Larimer County testing positive July 30 – the first two positive tests for virus in the state in 2019 – it’s more important than ever for residents to understand the life cycle of the insect to avoid bites and potential infection.

Water and temperature are critical to the mosquito life cycle, said Bob Hancock, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Biology at Metropolitan State University of Denver and an author of many on scholarly articles bloodsucking insects.

Consider the species Aedes hexodontus and Aedes Pullatus, a.k.a. snowmelt mosquitos. High above Pueblo in the Sangre De Cristo Mountains, locals and hikers are reporting swarms of skeeters stretching to the treetops. Each of those mosquitoes started as an egg laid in the earth last summer. Winter’s snows bury the eggs, which are protected by a thick outer layer, and the more the better, Hancock said. In fact, the more snow and the longer it takes to melt, the better the chances that the eggs of this species of mosquito will hatch as wriggling, wormlike larvae and mature into adults.

While snowmelt mosquitoes bite, they’re not known to be a vector for any human diseases. At lower elevations – in Pueblo, for instance, and across the Front Range – the mosquito species Culex pipiens and Culex tarsalis are the state’s principal vectors of West Nile virus, and they could be on the verge of intense outbreaks, Hancock said.

“The rate of development from egg to the pupal stage” – like a butterfly’s cocoon stage – “is entirely temperature-dependent,” he said. While snowmelt mosquitoes are just now getting attention after puddles have been forming for months, the hot-weather Culex mosquitoes will mature much more quickly after hatching.

“It can be on your arm in 12 days after hatching,” Hancock said.

One of the first things a female mosquito does in life is mate, he said. Then, that female will need a blood meal.

“Most of the mosquitoes that are biting us in Colorado also feed on a variety of other things – most (blood they consume) is from animals,” he said. “They take a tremendous amount of blood and convert the nutrient-rich substance into proteins for making eggs.”

Mosquitoes have a reputation for reproducing by laying their eggs in standing water, but Aedes vexans, for instance, hatch after hot thunderstorms and are more likely to have started out life in moist depressions in the ground – depressions that then fill up with rainwater, allowing the eggs to hatch. Females can keep stockpiling eggs in the same depression between storms, then the larvae hatch all at once.

“That’s when we can get incredible numbers of these kinds of floodwater mosquitoes,” Hancock said. “We’ve gotten to some hot, thunderstormy times, and I think that means we’ll get some hot spots and lots and lots of mosquitoes coming out.”

There’s a chance that one of Colorado’s West Nile-transmitting mosquitoes, Culex tarsalis, might not be so lucky this year, Hancock said. That’s because they primarily lay eggs in wetlands, especially cattail marshes such as those formed from water that seeps out below the dams of Colorado’s reservoirs, Hancock says.

Over his decades of researching mosquitoes in Colorado, he’s noticed that heavy snowmelt streaming through the state’s rivers and reservoirs may wipe out those Culex tarsalis eggs. For instance, in 2011, another year of heavy snowmelt, the state reported the fewest West Nile cases on record.

“I wonder if something about this flush could possibly play a role,” Hancock said.

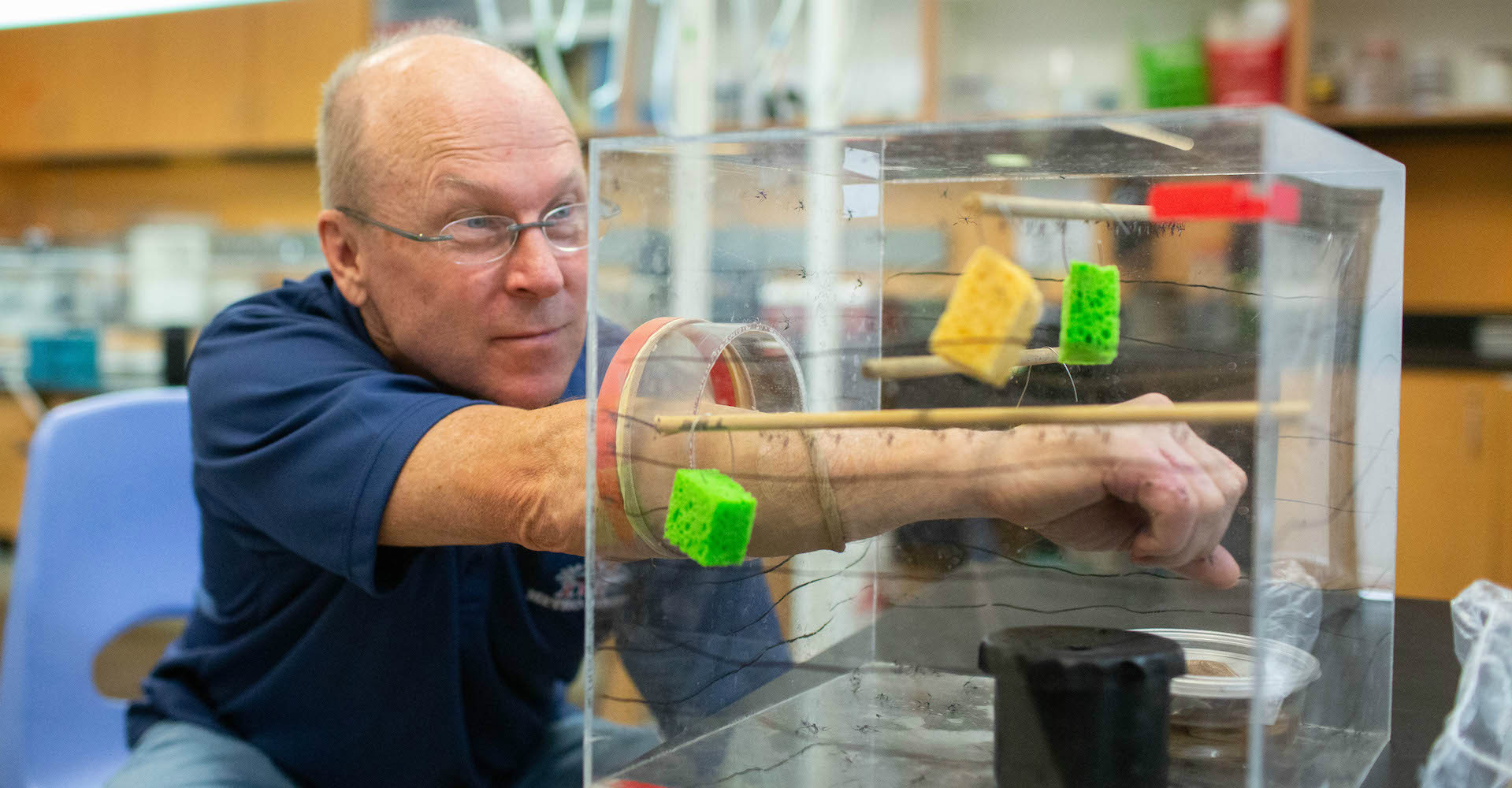

MSU Denver biology major Eric Reeve helps Hancock perform experiments on several mosquito species present in the wild in Colorado, comparing how the species react to different scents, for example. Studying the bloodsucking arthropods in the lab is a “dream come true,” he said.

While he respects that mosquitoes are vectors of serious human diseases, Reeve said the research has helped him gain more respect for mosquitoes as “an integral part of the local ecosystem,” with other species relying on mosquitoes as a food source.

“They became less of a nuisance bug to me and became a creature that has an actual purpose,” he said.

Still, it’s best to keep the mosquito population down, especially in densely populated cities. Here are Hancock’s suggestions for mitigating mosquitoes:

- Flip over water-collecting, slime-coated backyard tarps and buckets where mosquitoes like to breed, particularly in urban areas.

- Be aware that in the Front Range, mosquito activity peaks at dawn and dusk – especially dusk.

- Use insect repellent that contains the substance DEET. There are a lot of myths out there about DEET, Hancock said, but it’s an effective insect repellent. “I’m a mosquito professional, and I’m 100% in favor of repellent containing DEET.”

- Wear breathable, long-sleeve, light-colored shirts and long pants. Then you can spray the DEET on your clothes instead of directly on your skin.

- Take a head net along to the mountains.