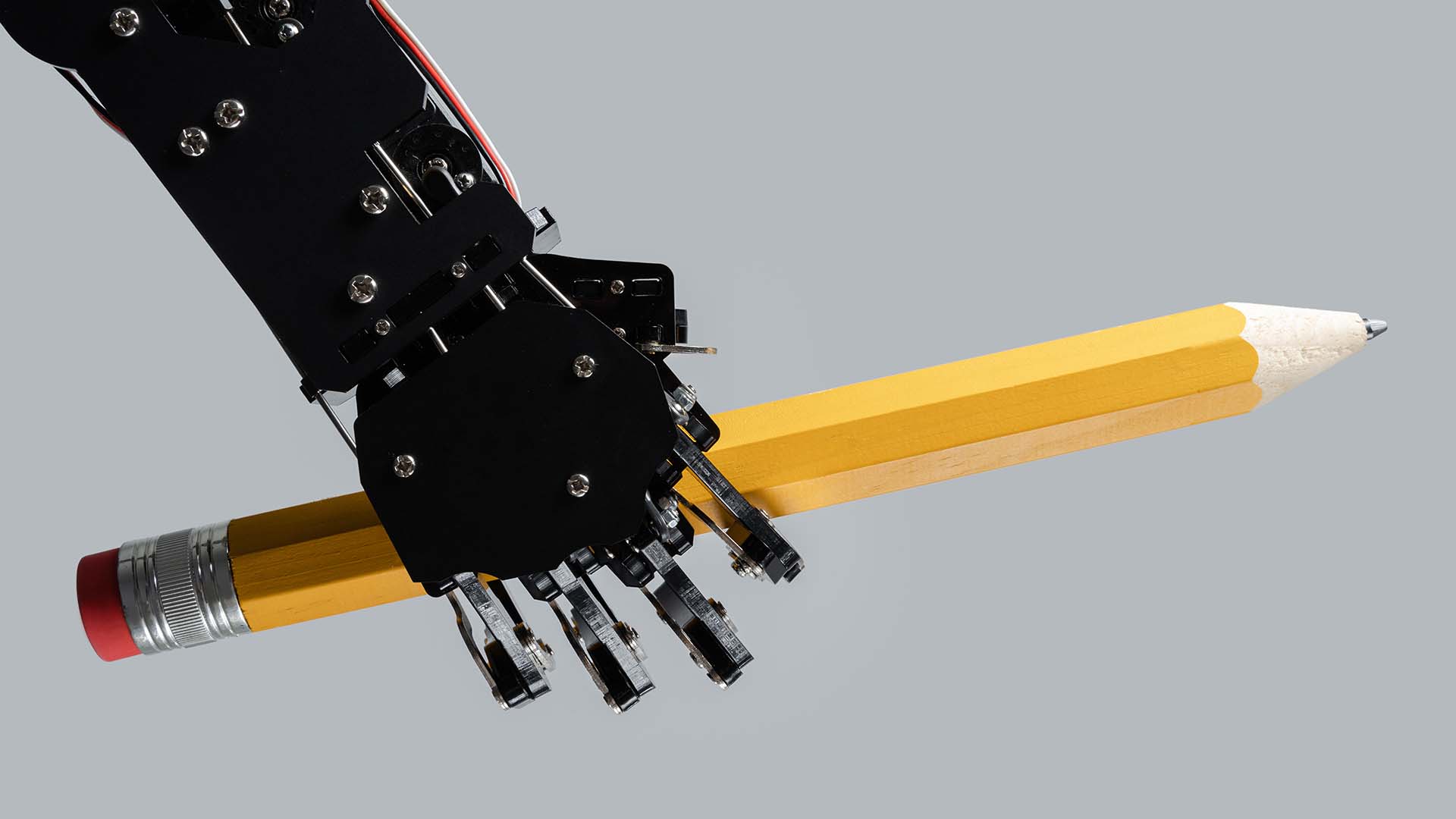

Future-proof: In journalism’s future, AI isn’t all bad news

Despite warnings of disruption, media scholars see opportunities for AI to support reporting, streamline tasks and reinforce the profession’s essential mission.

Last year, Colorado became the first state in the country to take a stab at regulating AI. The Colorado Artificial Intelligence Act, which is scheduled to take effect next year but may undergo changes in the meantime, is intended to protect people in certain sectors from bias that results from AI’s sometimes-discriminatory algorithms. It also requires developers of AI content to document and disclose sources. Around the country, half a dozen states are considering laws to rein in some of AI’s most worrisome traits.

It’s noteworthy, Jennings said, that states, rather than the federal government, are tackling AI regulation. Whatever laws that states devise will apply only to that jurisdiction, meaning we could see state AI laws that conflict with one another or with any future federal decisions on AI.

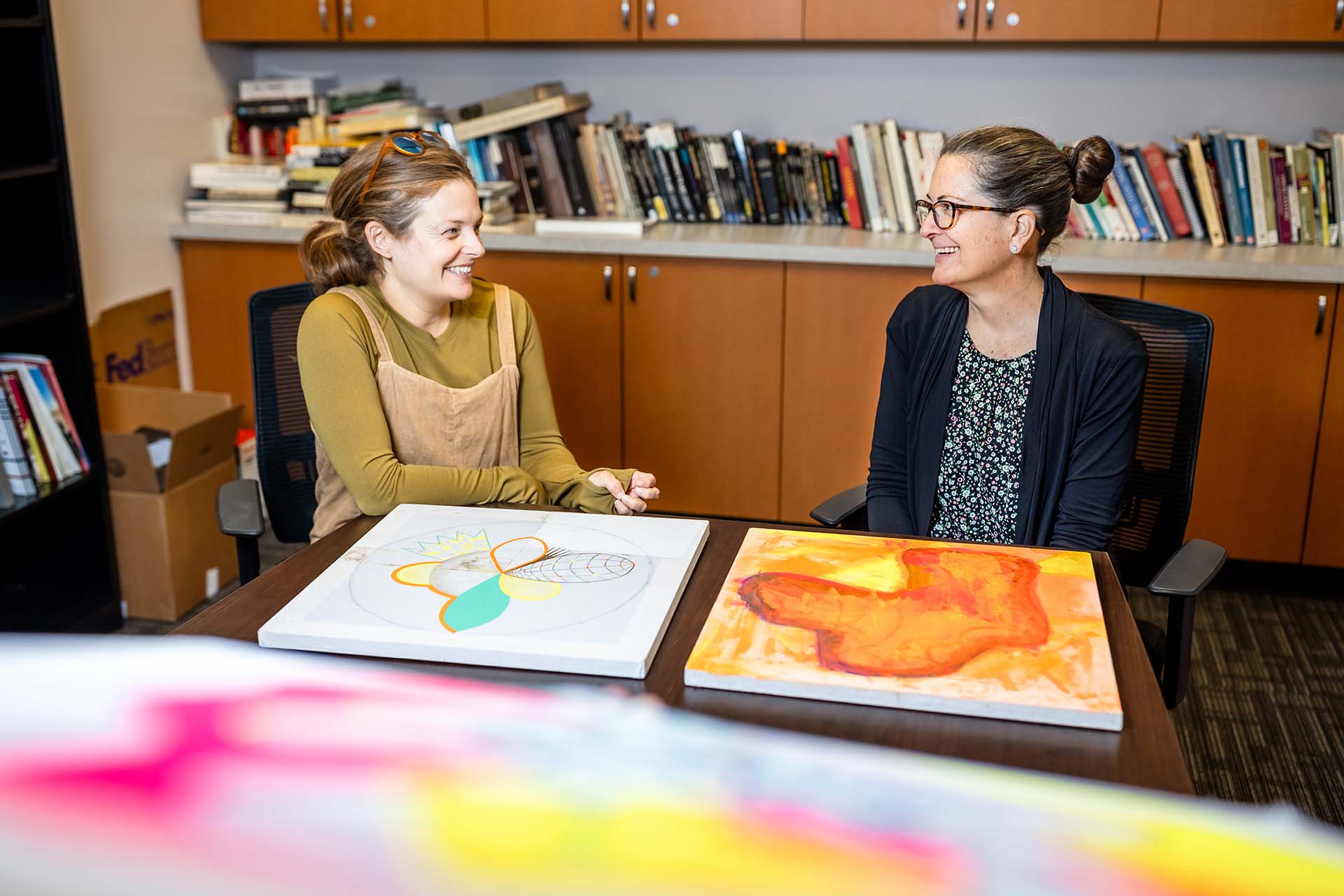

In the meantime, Jennings finds plenty to be hopeful about when it comes to his profession and AI. “The old way of doing journalism is changing in a way that is more conducive to the environment we live in now,” he said.

It’s possible that the technology “will allow us to do even more,” he said. “We have to find ways to utilize it for the good.”

RELATED: The future of journalism

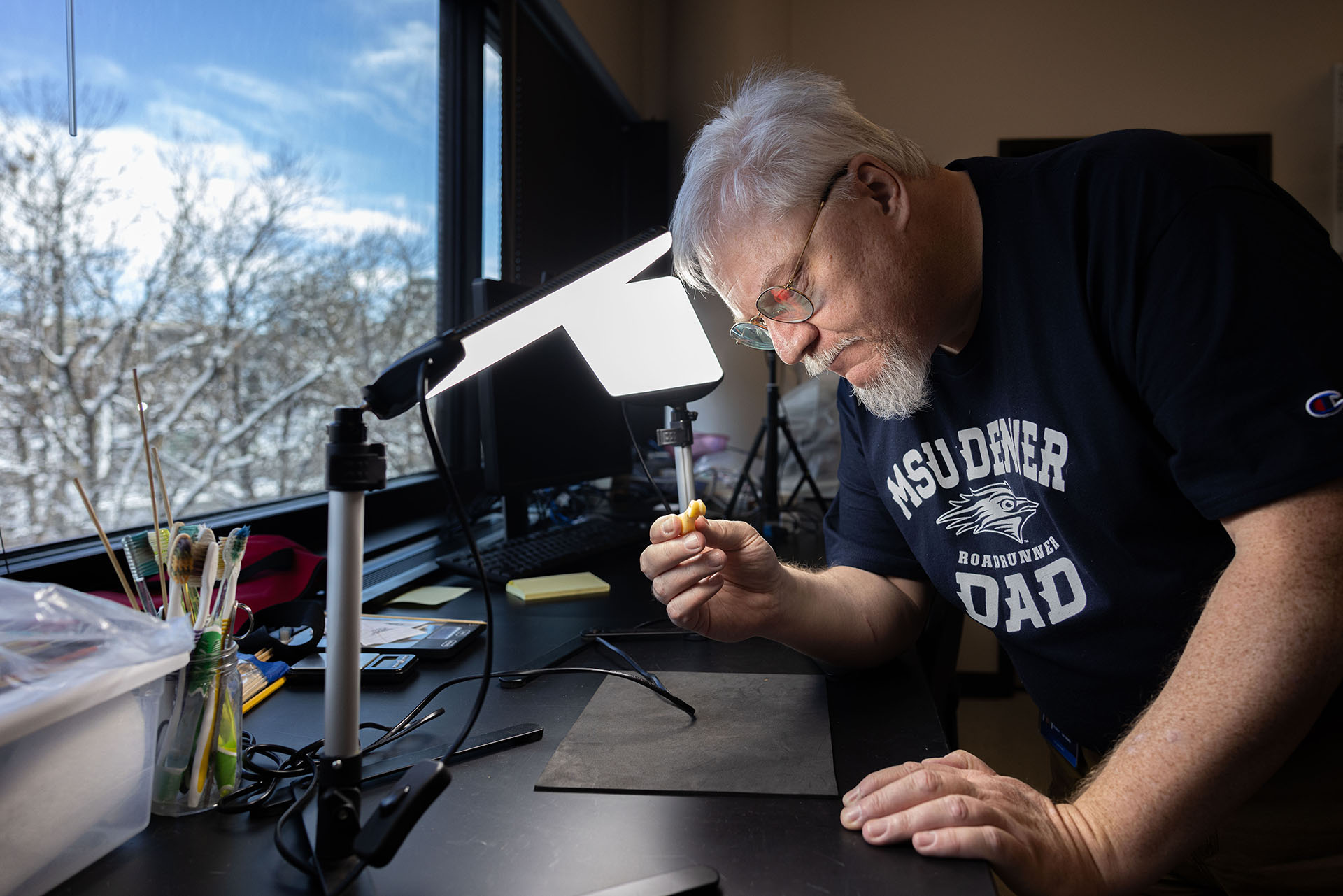

To help prepare students for that changing way of doing journalism, starting this fall, students in Communications Law classes will learn to use AI in positive ways: “how you can use it not to do your work but to help with your work,” Jennings said. Examples include learning how to create prompts that will guide students through fair-use laws and using AI to perform more mundane tasks such as creating permission forms.

He’s also philosophical about the potential for AI to increase the amount of disinformation and misinformation circulating. “The first fake news was on a cave wall,” Jennings said.

The problem isn’t so much that bad actors create content they know is false. It’s that others eat it up and spread it around, he said. “There was an MIT study a few years ago that said lies travel faster than truth,” he said. “That’s on the internet or any media.”

One explanation for that could be the way those stories are presented. The more salacious, the more colorful and attention-getting the language used to tell the story, the more attention it gets, he said. That’s where AI could be helpful. “AI can help in being more creative in telling the truth,” Jennings said. “It can help us craft it in a way to tell the truth and still get readers’ attention.”

RELATED: How students should — and shouldn’t — use artificial intelligence

The Microsoft findings drew widespread attention, despite what some might consider serious red flags. First, the study was conducted by Microsoft, which may not be exactly unbiased about AI. In addition, Microsoft relied on data provided by users of its search engine, Bing. While the number of people using Bing worldwide has jumped recently to an estimated 1.8 billion a month, that’s still a fraction of Google’s 5.6 billion.

That’s the kind of information Jennings is hopeful that credible journalists and media outlets will continue to ferret out. “We’re teaching critical thinking — to look at what is the source and what angle are they coming from, whether advertisers or corporate interests might skew what’s being represented.”

Jennings is so optimistic about AI’s potential for good that he dares to imagine the seemingly impossible. “Hopefully,” he said, “someone will create an engine that can sniff out fake news.”

Learn about Journalism and Media Production programs at MSU Denver.