Beyoncé’s ‘Cowboy Carter’ tour honors the legacy of the Chitlin’ Circuit

With just nine stops, the tour pays tribute to the Black musicians and venues that shaped American music in the shadows of segregation.

Beyoncé’s “Cowboy Carter and the Rodeo Chitlin’ Circuit” tour includes just nine stops — an intentional choice with historical significance.

Unlike her Renaissance tour in 2023, which hit nearly 40 cities, this tour is more constrained, stopping in Los Angeles, Chicago, New Jersey, London, Paris, Houston, Washington, Atlanta and Las Vegas.

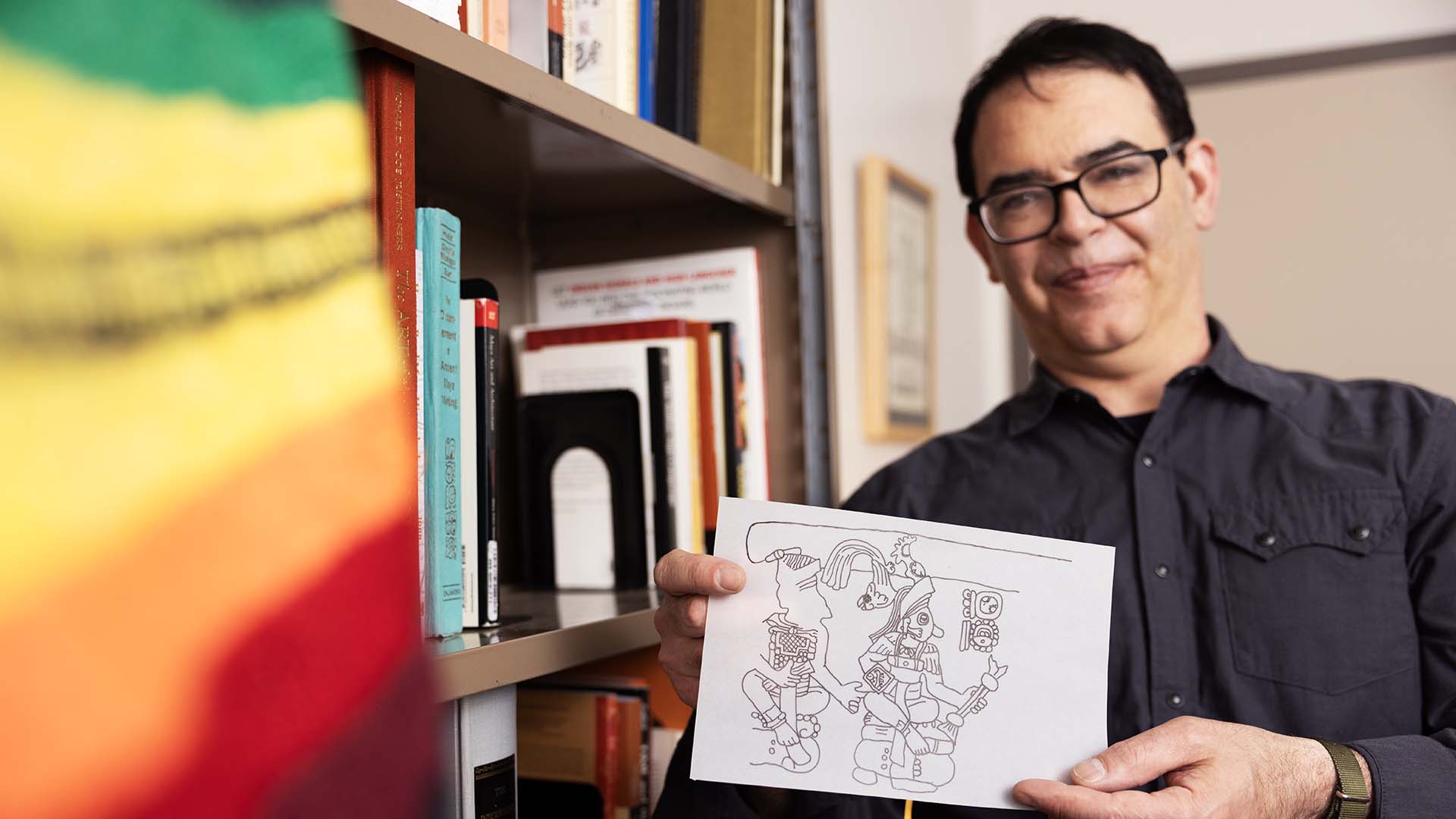

But the U.S. cities on her tour aren’t just about scaling back. There’s a deep historical significance behind her choice of locations, said Jasmine Harris, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Africana Studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

“The album and tour are about more than just music,” Harris said. “Beyoncé is using her platform to reconnect people with a history they’ve been separated from. She’s educating while entertaining.”

Safe spaces for Black musicians

The tour’s title hints at the history Beyoncé pays tribute to. The Chitlin’ Circuit was a network of venues where Black musicians and entertainers could perform during the Jim Crow era, a time when mainstream (mostly white-owned) venues wouldn’t book them.

“Like so much else in American life, it started with enslavement, racism and racial discrimination,” said Harris.

After emancipation, job opportunities for Black people were scarce, and many Black men and women turned to music to make a living.

“The venues, known as juke joints, were often tucked away in places meant to avoid white scrutiny,” Harris said. “They became safe spaces where Black musicians could perform and Black audiences could dance, celebrate and just feel joy.”

Even though Black musicians pioneered many of the U.S.’s greatest musical genres, such as blues, jazz and rhythm and blues (a.k.a. R&B), their work was often overshadowed or outright stolen. Artists such as Elvis Presley made Black musical styles mainstream, but Black performers were largely shut out of major venues.

“The Chitlin’ Circuit became a kind of underground tour for Black musicians, allowing them to perform and build their careers despite segregation,” Harris said.

RELATED: Songs to sustain a movement

Many of these artists risked their lives to get to these venues. While traveling, they often passed through “sundown towns” — places where Black people weren’t welcome at any time and faced potential violence if they lingered past dark.

“Not only could they not perform at white-only venues, but they also literally couldn’t be in town,” Harris said. “So they created their own touring circuit, which became a launchpad for so many legendary artists.”

The Chitlin’ Circuit’s lasting impact

Most of these venues were in the South for two main reasons: First, Jim Crow laws and racial violence there made it nearly impossible for Black musicians to perform in white-owned establishments. And the South was home to the nation’s largest Black populations until the Great Migration in the mid-20th century.

“What started as a punishment for being Black turned into something powerful,” Harris said. “It allowed Black musicians to develop national followings and create fame on their own terms.”

Touring on the Chitlin’ Circuit wasn’t just about finding places to perform — it was about survival.

“The biggest danger was violence,” Harris said. “Black performers faced the constant threat of being lynched or attacked just for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

RELATED: Member of the Little Rock Nine shares her story of desegregation

On top of that, the pressure of life on the road, combined with racism and segregation, led some artists to struggle with addiction.

“It became a kind of prison,” Harris explained. “These musicians had incredible talent, but because of their skin color, they were stuck performing in a limited number of cities instead of reaching the whole world.”

Still, one of the most fascinating things about the Chitlin’ Circuit was how much genre-blending happened.

“There weren’t a ton of venues, so artists from different genres — blues, jazz, R&B and even country — often performed at the same places, sometimes on the same nights,” Harris said. “They learned from each other, and that’s why you hear so many overlapping influences in Black music.”

Through “Cowboy Carter,” Beyoncé isn’t just making music; she’s telling a story. She’s highlighting artists like Linda Martell, one of the first Black women in country music and a former Chitlin’ Circuit performer.

In addition, enslaved people historically worked as cowboys on ranches, handling cattle and horses — something that’s often left out of mainstream history.

“I think what Beyoncé is doing is reintroducing a generation of Black people to country music,” Harris said. “She’s reminding people that country music and cowboy culture have deep Black roots.”