Russian invasion tests the international order

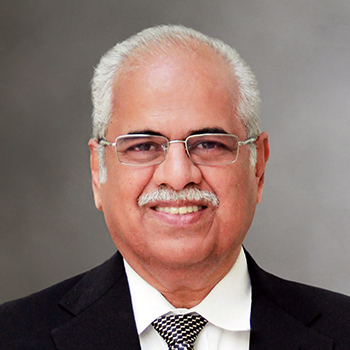

MSU Denver President Janine Davidson, former undersecretary of the Navy, says NATO alliance and nuclear weapons dictate the terms of involvement in Ukraine.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is barely three weeks old, but the war has had devastating effects: loss of military and civilian lives, disruption to the global economy and massive migration out of Ukraine and into neighboring European nations.

The conflict is also a stress test of NATO alliances that have been built over decades, said Metropolitan State University of Denver President Janine Davidson, Ph.D., who was appointed to the U.S. Department of Defense Policy Board in December and previously served as the undersecretary of the U.S. Navy and deputy assistant secretary of defense for plans.

The outcome of the conflict has ramifications far beyond Europe and NATO, Davidson said.

“The NATO piece is important, but it’s also about the demise of the post-World War II international order,” Davidson said. “We are basically reverting back to a ‘might makes right’ mentality, where just because you can invade a country, you’re allowed to, and the international community is helpless to stop you. So the test here is whether the international community is helpless and whether the most serious economic sanctions I’ve ever seen actually work in reversing a full-scale military invasion.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin has characterized the invasion as a “peacekeeping” mission involving two former members of the Soviet Union. Also staving off the addition of Ukraine into NATO by allied Western forces, Putin sees the growing number of countries that have joined NATO since the fall of the Soviet Union as a threat to historical Russian territory. The alliance of North American and European countries was established in 1949 and has nearly doubled its membership to 30 countries since 1999.

Editor’s Note: Finland became the 31st country to join NATO in April 2023. Sweden has also applied to join the alliance.

Davidson said NATO expansion isn’t the viewpoint at all in the many European countries that have more recently allied with Western powers such as the United States. Davidson recalled a Czech delegate telling a friend in the 1990s that, “NATO isn’t expanding to the east. … We are running to the west.”

What isn’t up for debate is Article 5 of NATO, the collective defense provision that binds NATO countries together to defend one another if any are attacked. NATO membership is a critical factor in the Russia-Ukraine crisis, as is possible U.S. military involvement, even though Ukraine is not a member of NATO. The chance of the conflict “spilling over” into NATO territory or of NATO getting dragged into a hot war to defend Ukraine is a serious threat.

Davidson said that in addition to Putin’s desire to take Ukraine as Russian territory and prevent it from joining NATO, he hopes to disrupt the alliance. But so far, his efforts on that score have backfired.

“Instead of being freaked out, the NATO countries actually solidified, and it’s exactly the opposite of what he wanted to have happen,” she said. “Now if he actually does test that electric fence and we don’t defend wholeheartedly as an ‘attack on one is an attack on all,’ it will be the end of NATO. I don’t expect that to happen.”

Four NATO countries share a border with Ukraine, and the three Baltic nations that border Russia are also members. Davidson said the alliance has militarily reinforced NATO borders in the past decade and has worked through potential scenarios for conflicts like this one for years. She also said U.S. and NATO forces are more sophisticated than Russian troops, which could make Putin more dangerous.

“Because there’s a perceived overmatch for us against Russian conventional forces, it drives people like Putin to agitate on the edges,” she said. “Conventionally, I can’t win by punching you in the nose, so I’m going to have a cyberattack or a nuclear attack — you either go low or you go high — but to stay in the middle, you know you’re going to lose. And that’s another reason why confrontation with Russia is so concerning, because the risk of it getting out of the conventional arena where we would prevail more easily is scary.”

RELATED: Cyber superheroes prepare for battle

Because of increased tension in the region, there is also a risk of accidental escalation.

“When I was undersecretary, the Russians used to torment our ships in the Mediterranean and the Baltic Sea. There were always cat-and-mouse games. That was bad, and it still happens,” Davidson said. “That always makes it scary that there could be a risk of miscalculation because now the tensions are higher and there are more ships out there, and that’s how things can spiral into an accidental war.”

American avoidance

Of course, the U.S. just withdrew from a 20-year war in Afghanistan. A majority of Americans were in favor of the withdrawal while viewing the war as a failure. The longest war in American history casts a long shadow over the country’s foreign-policy strategy.

“The Biden administration is keenly aware that Americans are weary of military intervention abroad,” Davidson said. “Additionally, the United States’ national-security leadership has been trying to get out of the Middle East for forever so they can focus on deterring China. But you don’t always get to choose your enemies.”

Putin is also using U.S. interventionism as reasoning to invade Ukraine, Davidson said.

“Russia was highly critical of all the stuff we were doing in Iraq and Afghanistan and, in some ways, rightly so. The U.S. went to Iraq with weak and bogus reasoning. It turned the country upside down and left the region worse than when it started. It was a tragedy. It also unleashed ISIS, which generated the tragedy in Syria, and the Russians were also upset when we did airstrikes on Libya. So Putin’s attitude is, ‘You screwed up all of these things, and all we want is Ukraine back.’ He takes our rationale, which was not great at times, and twists it around. It’s definitely connected.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has called for the U.S. and its NATO partners to institute a no-fly zone in Ukraine to prevent Russian airstrikes on military targets and civilians, which Davidson said is usually feasible only after a ceasefire, if at all.

“Right now, they’re in the middle of an active conflict. You would be entering the war,” she said. “We’re still offering arms, but we’re not putting our own boots on the ground or flying our own planes over there because then we would be at war with Russia. Right now, we’re just robustly supporting someone who’s being invaded by Russia, and that’s a distinction that matters.”

When a Russia-backed Ukrainian president was removed from office in 2014, the rest of Europe and the U.S. supported the new Ukrainian government while Russia annexed Crimea and seized disputed territory in eastern Ukraine. The U.S. provided Ukraine with nonlethal military assistance at first, then later a package with surface-to-air missiles and small arms.

“From 2014 until now, there has been a lot of U.S. and NATO support to Ukraine to help them resist what’s going on in the east and training and equipping their special forces. You see that paying off now. Russia’s forces were a lot less capable than Putin thought, and Ukrainian resistance was a lot stronger than Putin thought,” Davidson said.

Historians weigh in

Metropolitan State University of Denver President Janine Davidson, Ph.D., joined MSU Denver History faculty for a “Ukraine Conflict in Context” panel, where panelists dug deeper into the relationship among Russia, Ukraine and the rest of Eastern Europe.

“Ukraine, because of identity politics, is essentially two states,” said Andrea Maestrejuan, Ph. D., associate professor of History, noting the percentage of Russian-speakers in the eastern half of Ukraine that borders Russia, as well as contrasting voting trends that divide the country. Putin has used the number of Russian-speaking Ukrainians as a pretext for invading the sovereign nation.

“(Putin’s) strategic concerns have always been consistent,” Maestrejuan said, “and his perceived attitude toward Western intransigence to these security concerns leaves us with a stark reminder that he drew the red line at Ukraine.”The war is personal for Cristina Bejan, Ph.D., an affiliate faculty member who has family in Romania, Ukraine’s southwestern neighbor. Bejan’s father fled Romania during the Cold War. Her grandparents were imprisoned by Soviet-backed dictators, and her great-uncle spent a decade in a Romanian labor camp.

“It’s really important to put ourselves in other people’s shoes,” Bejan said. “There is a fear that Putin is not going to stop. There is a very real fear that he is not only going to take Ukraine but also Moldova, which is not a member of NATO. There’s a real fear that he will take NATO countries such as Romania, which has a very sizable border with Ukraine.”

Bejan has protested at the state Capitol and is actively working with nongovernmental organizations in the U.S. and Romania to help refugees.

“There’s a lot of fear on the ground there. We are experiencing a war, but we’re also experiencing a global humanitarian crisis,” she said.

The panelists also addressed why this war has gotten more attention from Americans than other global conflicts and why we should get involved at all.

“There is a geopolitical answer to the question, which is nuclear weapons and NATO, and that scares a lot of people,” Davidson said. “And why don’t we just say, ‘Go ahead and take it’ then? It’s because we aren’t supposed to be like that anymore. We’re clinging to our international norms. … Just look at the history of the 20th century, when we were trying desperately not to let that happen. There’s a domino effect, a very great fear that if you let one country go, they just keep going.”