What can history teach us about Jan. 6?

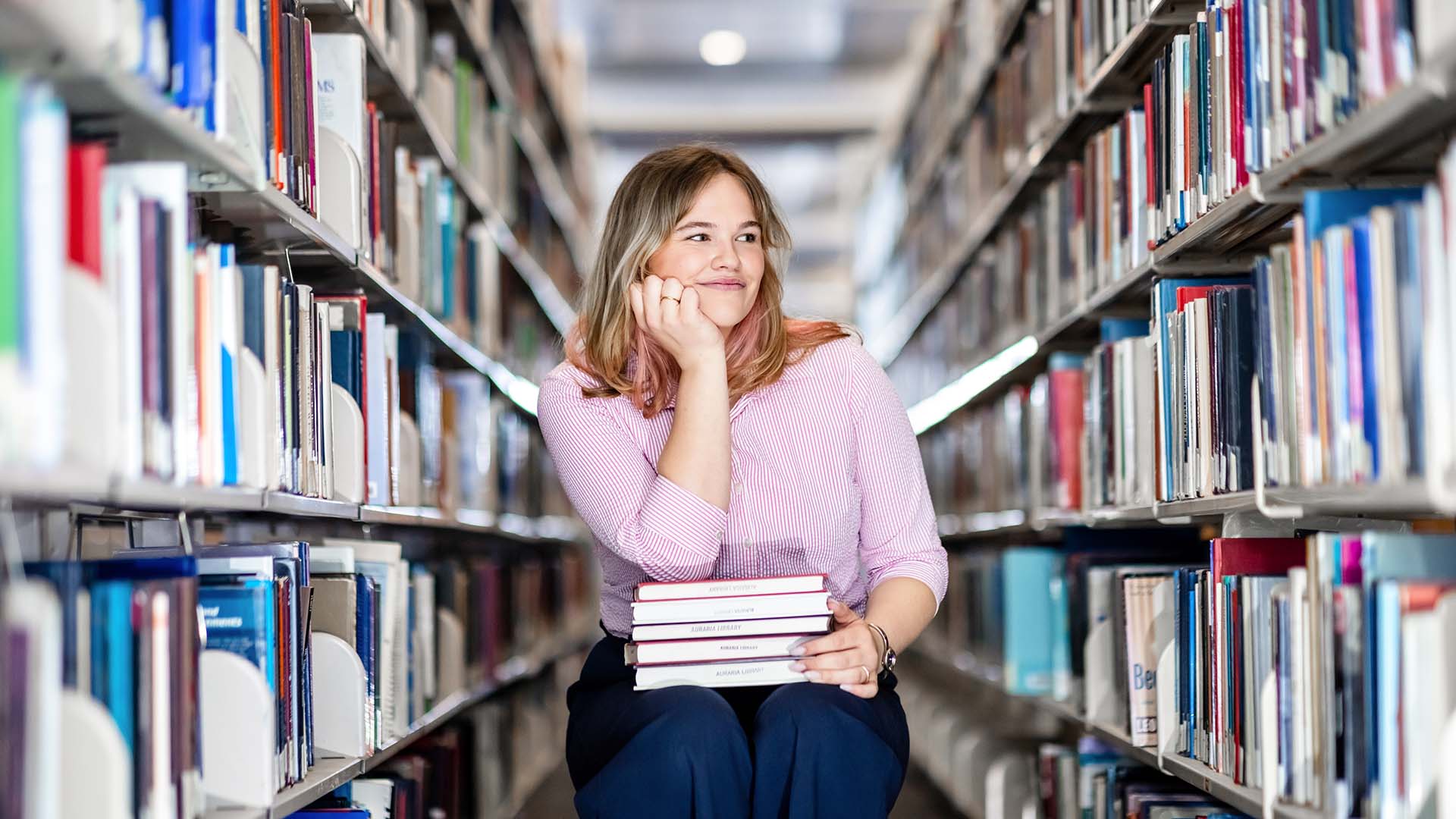

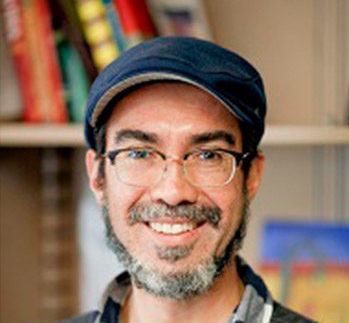

Associate Professor Shelby Balik draws parallels from the past to help us understand the recent attack on the U.S. Capitol.

If there’s one word we could use a little less of in 2021, it’s “unprecedented.”

In the wake of the violent mob that stormed the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, RED caught up with Shelby Balik, Ph.D., associate professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver, to learn what the past might teach us about our chaotic present and the uncertain road ahead.

Are there any moments in U.S. history we can compare to what just happened?

Shelby Balik: It’s certainly not the first time Americans have used violence to reverse or interfere with our democratic election process. The Civil War is the most obvious and remarkable example; even though the South seceded to preserve a system built upon the institution of slavery, the triggering event that set it into motion was the election of Abraham Lincoln.

Another example was in 1898 in Wilmington, North Carolina, post-Reconstruction. White supremacists took over the city in a violent riot after the election of the progressive integrationist Fusion Party and retained power throughout the Jim Crow era.

Not to say that the left hasn’t used violence before, but it is typically used to express discontent with the current political system rather than reverse an election. What we just witnessed last week fits into a pattern, particularly on the far right, to interfere with our democratic election processes through violent protest.

Why the far right?

Historically, conservatism has to some extent placed higher hurdles for participation in civic life; the definition of who is or isn’t considered part of the “in-group” becomes more exclusive and helps conservatives retain their power by placing barriers for entry.

Again, this isn’t to absolve liberal ideology of wrongdoing. But in this specific context, if you’re of the mindset that people have to prove themselves before they can participate in American society, you can connect the dots on how rhetoric around illegitimacy can stoke the flames of resentment.

We’ve lived through questions of election integrity before.

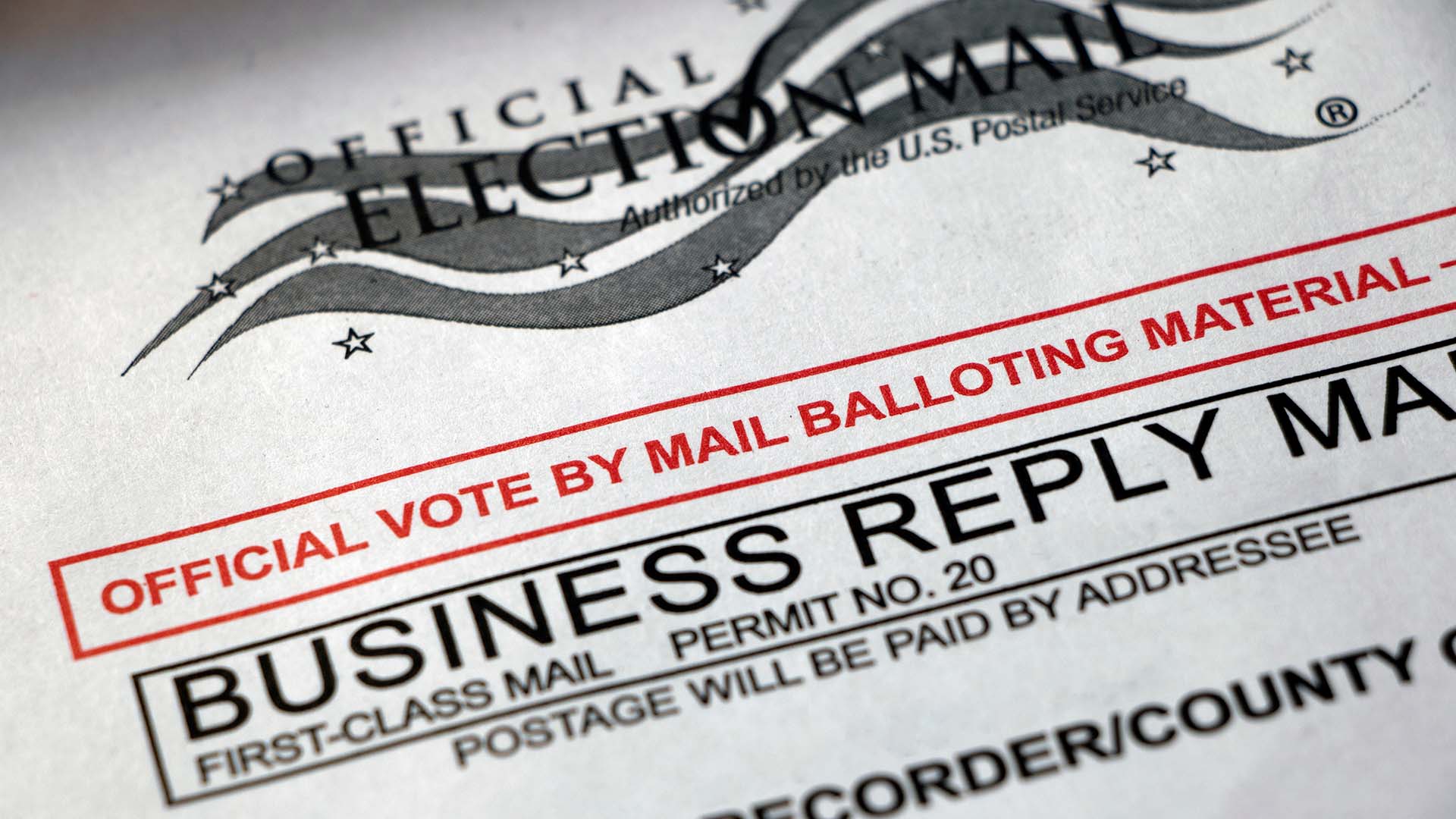

Historically, elections through the early 20th century were rife with corruption and illegal influence – that was the norm. Progressive reforms were then introduced at the federal and state levels, like private voting booths and anonymous ballots, so, for example, your boss couldn’t look over your shoulder and watch you vote.

Voting has always been run by states and counties, which have tremendous authority to determine their own procedures. Then, during the Obama era, the right started focusing on things states have been doing for a long time, such as same-day registration and not specifically requiring a driver’s license to vote.

We’ve seen this narrative emerge most commonly in states like North Carolina, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Texas and Georgia, where voter-disenfranchisement efforts – primarily in communities of color and lower socioeconomic status – have picked up. Wisconsin’s an interesting case, as it’s widely regarded as having a notably clean process and a place where you’ve long been able to walk up on Election Day and register with a utility bill and vote. But now, it has some of the most restrictive voting laws in the country. We saw the myth of widespread voter fraud being stoked well before November, however. And if you’ve got a large portion of the population primed for that messaging, the rage we saw boil over Jan. 6 emerged as sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When has the U.S. Capitol itself been under attack before?

The War of 1812 was waged primarily in the Mississippi Valley and the Great Lakes region. But in 1814, the British staged a surprise invasion of Washington, D.C., and burned the White House and the Capitol. That was an external invasion, as opposed to a domestic one.

In 1954, a Puerto Rican nationalist group staged an armed occupation of the Capitol; several members of Congress were injured without fatalities, and the perpetrators were quickly arrested.

A couple other bombings of the Capitol have occurred too, usually led by solitary actors: a German nationalist in 1915, a small group protesting the bombing of Laos in 1971 and after the U.S. invasion of Grenada in 1983. These caused a lot of destruction but were specifically carried out after hours, and no injuries or deaths occurred. Nothing has ever happened in the Capitol that compares to the insurrection on Jan. 6.

Some have made comparisons to the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch in Germany, where Adolf Hitler led a failed coup attempt. What do you see as the parallels and difference?

That was another sudden, violent takeover attempt, which was quickly put down. Hitler and his supporters were punished lightly by those in power, who wanted to forge a compromise and move on. But the white-nationalist sentiment remained, and within a decade it propelled Hitler to power. It’s a legitimate comparison as we don’t want to fool ourselves that problems just go away when people responsible for violence are punished or arrested.

However, Trump is not Hitler for a lot of reasons – the former is in his 70s, so it’s hard to imagine him coming back in a decade regardless of what punishment he may face. The question we should ask, however, is how Trumpism will take shape after he’s gone. What we saw on Jan. 6 reflects not just an extreme ideology but a seething resentment that exploded in a flash point.

We live in a time of widespread misinformation and cynicism about media. Is there a historical precedent for what we’re experiencing now?

In the 1790s, Americans were deeply concerned about the proliferating print media, especially partisan newspapers. Party politics were new, and a lot of people, specifically in the Federalist majority, thought they were overtaking national loyalty. Partisan newspapers were escalating those rivalries, and they were very much a topic of concern, often blamed for ideological divisions, as in the Whiskey Rebellion, which was fueled in part by rumors and heated rhetoric in Democratic-Republican newspapers.

That’s an example of a new media platform in the 1790s contributing to misinformation; these publications were not fact-checked and were extremely biased. The political division led to the nation’s first constitutional crisis over civil liberties – the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798.

What can history tell us about where we go from here?

It’s difficult to say exactly. In the 1920s, with the rise of the Klan, we saw moments of intense racial violence and racist rhetoric, which was somewhat interrupted by World War II, which forced most Americans to take a stand against a fascism targeting ethnic minorities. That was a moment of collective resolve – but then the 1950s saw the reemergence of inequitable social systems around the country, and the Jim Crow system in the South survived as entrenched as ever.

Many people are calling for displays of unity, but unity without accountability just covers up the root cause of what’s happened. It’s a pattern we see through the years and in many ways is similar to what happened after the Civil War; calls for unification muted a brutally honest assessment of the South’s efforts to preserve slavery through secession and war.

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass lived into the 1890s and continued to push for America to reckon with its history. This was opposed by both whites who wanted to hide the truth behind the Civil War and some African Americans who didn’t want to relive the trauma of slavery by dwelling on it, but Douglass kept advocating for a deeper acknowledgment. The process of just forgetting and moving on, whether then or now, puts us at risk for forgetting how we got here in the first place.