Catching up in the classroom

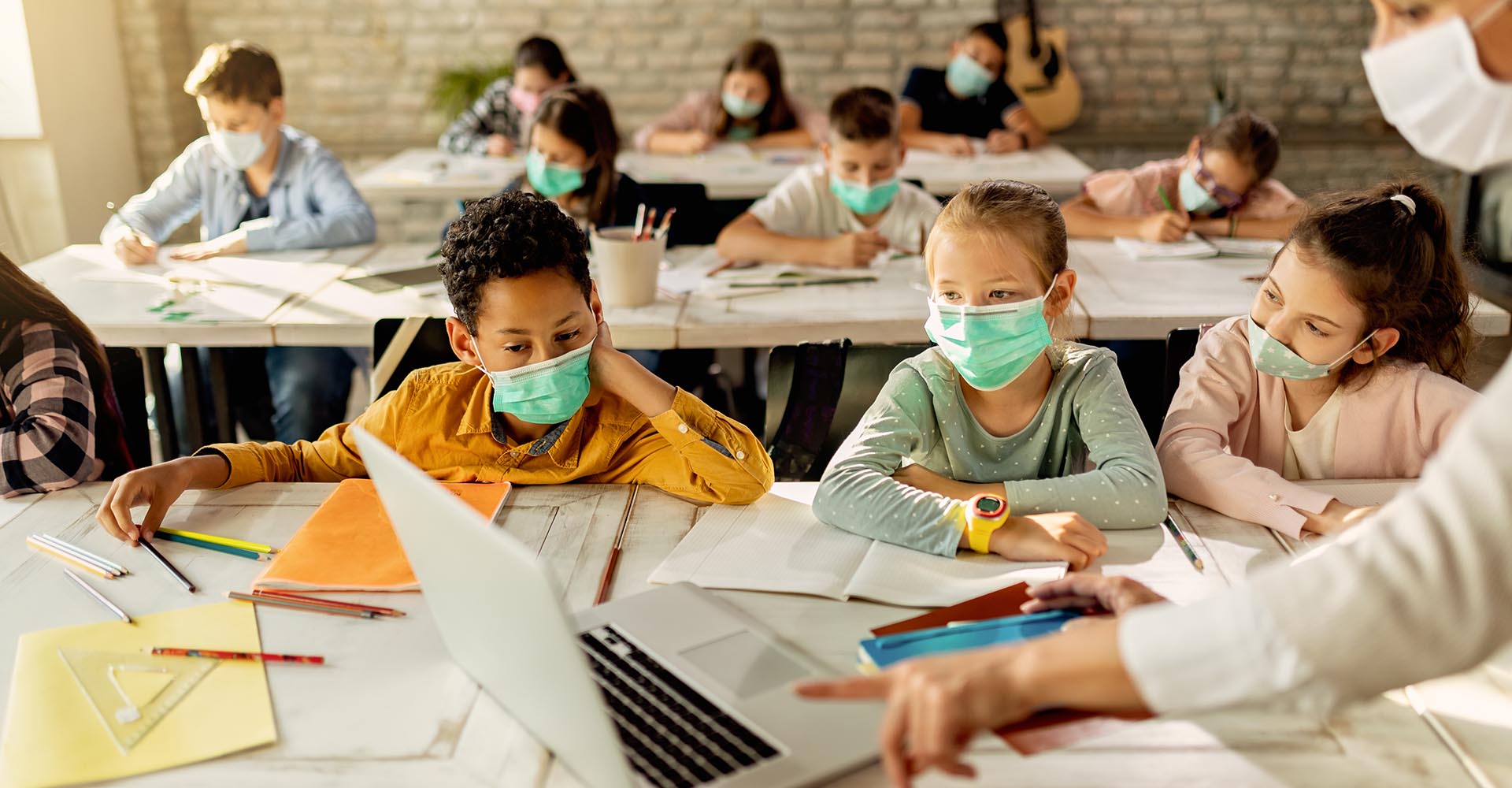

The pandemic has had a devastating impact on K-12 students. Now, the race is on to help them catch up.

The Colorado Department of Education this month released standardized-test data from 2021, providing a first look at how the pandemic has impacted learning. The results painted a bleak picture of the academic progress in the state, with a decline in all grades and subject areas compared with 2019. Students’ math performance, in particular, sank to an all-time low.

Colorado’s data reflect a broader trend playing out across the United States. Analysis from McKinsey and Co. shows that on average the pandemic school year left K-12 students five months behind in mathematics and four months behind in reading.

How parents can helpSix tips for parents to get their kids caught up this school year: Read to your young children Provide nourishing meals Remember: Sleep counts Encourage other interests Watch the watchers Praise their achievements |

|

Elizabeth Hinde, Ph.D., dean of the School of Education at Metropolitan State University of Denver, said the chaotic 2020-21 school year turned students’ lives upside down with months of lost learning time, mental-health difficulties and no real sense of structure. For many, this also happened against a backdrop of anxiety and disruption at home, as families were crammed together and often had to deal with financial uncertainty.

“Not knowing what to expect from week to week is never good for learning, and that’s the world we lived in last year,” she said. “Home-schooling brought numerous challenges as students struggled with unequal access to devices, connectivity issues and lots of miscommunication.”

She also noted the difficulty teachers faced in switching back and forth between having students physically in front of them and then on a screen, with each setting demanding a different energy.

“From both a teaching and learning standpoint, this jumbled-up approach didn’t always lead to great outcomes,” Hinde said.

Widened achievement gap

While virtually all K-12 students suffered through the pandemic, the same CDE data showed Black and Hispanic students being disproportionately impacted during the past school year across all grades.

“Sadly, this particular achievement gap is nothing new in education,” Hinde said, “but I think the pandemic both shone a bright light on it and may even have widened it.”

Hinde suggested a three-pronged approach to tackle the historic challenge. First, the obvious one: Provide more resources for schools in predominantly Black and Latino communities. Second, she argued that more families need to champion, not criticize, the hard-pressed teachers in those schools.

“The more that teachers feel supported, both morally and emotionally,” she said, “then the better they will be.”

And third, she encouraged more families to take advantage of numerous community programs around Denver that focus on helping children, as well as MSU Denver’s own Family Literacy Program.

Making up ground

Here’s the good news: There is a plan to help all students catch up.

“Even now,” Hinde said, “teachers and schools are gearing up to cover as much missed material as they can, as quickly as possible, to help bring students back up to speed.”

Besides accelerated learning in Colorado’s classrooms, Hinde said other concrete measures are being prepared. New tutoring programs are hiring college students to further support schoolchildren. After-school programs are being redesigned to focus more on education. And numerous community organizations such as Boys and Girls Clubs are stepping up to help. Teachers will also provide extra support for families eager to do a little extra with their children at home.

“It’s difficult to know exactly how much of a learning loss there has been as a result of the school shutdowns,” Hinde said, “but everyone realizes that just doing business as usual won’t get us back to where we need to be.”

She conceded that it will take a strong coordinated effort to get children in Colorado fully caught up on their studies, but argued that that’s simply what educators will have to do.

“There isn’t really another choice,” she said. “Our children’s futures depend on it.”