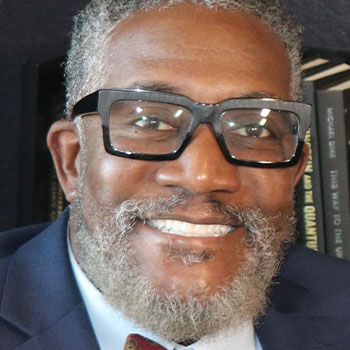

This future teacher is dedicated to opening STEM to students with disabilities

When multiple sclerosis derailed his Ph.D. research, Joe Schneiderwind dedicated his career to teaching math and science – and shining a light on the underrepresentation of people with disabilities in STEM.

Despite efforts to improve representation in STEM fields, students with disabilities are not only underrepresented in STEM classrooms; they’re also largely missing from the discussion about who is underrepresented.

A survey of academic literature by Metropolitan State University of Denver School of Education students and professors shows significant gaps in research on students with disabilities enrolled in STEM classes. The review of four higher-education academic journals found just 25 peer-reviewed articles on students with disabilities in 20 years, or about 1% of the research on higher education. Likewise, they found that research on that student population has become less frequent over time, even though college admissions of students with disabilities have increased.

For the report’s co-author and future math teacher Joe Schneiderwind, the findings and potential solutions are personal. Multiple sclerosis forced the former National Defense in Science and Engineering graduate fellow to leave his Ph.D. program in 2016. He decided instead to pursue his other passion: teaching math and science.

“I always had it in the back of my head that teaching would be a good option,” said Schneiderwind, who expects to graduate from MSU Denver’s teacher-preparation program in spring 2021.

Reimagining teacher preparation

Schneiderwind completed his research on representation in STEM alongside School of Education Associate Professor Janelle Johnson, Ph.D., whose multicultural education class helps teacher-education students see their own biases and the systemic disadvantages built into U.S. education structures.

One reason for achievement gaps in STEM among marginalized populations is the “expectancy effect,” Johnson said. It’s challenging for students who don’t see others like them in a given field to see themselves choosing that career path.

“Students are being tracked out of a pathway that could open up different kinds of careers or coursework to them. The message is, ‘This isn’t for you,’” she said.

In teacher-prep programs across the country, most students take one introductory class related to special education, which isn’t enough to fully prepare them to work with students with disabilities, said Rebecca Canges, Ed.D., associate professor of special education at MSU Denver.

The School of Education is shifting how special education is incorporated into the teacher-education curriculum to better prepare all teachers to work with students with disabilities, she said.

“Our (teacher-education) students take more elementary classes and more secondary classes, in hopes of collaborating more with those that are going to be future general-education teachers,” Canges said.

General-education teachers can learn more about helping students with disabilities from their special-education colleagues, she said, while special-education teachers gaining experience in specific content areas will help students with disabilities.

Providing students with special needs with opportunities in general-ed classes, instead of being siloed in special-ed tracks, is just as important as access to the STEM curriculum, Canges said.

“If students aren’t included in science classes, they’re not even getting the exposure to the subject,” she said, “or if they’re told, ‘You have a disability, so this is too hard for you,’ they give up and it perpetuates a vicious cycle.”

Finding his voice

For Schneiderwind, studying the seismo-acoustic underwater environment of the Arctic Ocean for the U.S. Navy was simple compared with the physical act of writing out and publishing his findings, which involved complicated mathematical formulas.

“I was figuring it all out myself,” he said. “I was completely unaware of what was available to help me do the programming and high-level computing that were necessary for me to do that type of work. That fits into the ‘invisibility’ piece that I’ve struggled with and am trying to change.”

In his teaching career, Schneiderwind will rely heavily on voice-to-text computer programs, he said.

Having completed much of his academic career prior to the onset of MS, he’s excited to bring a unique perspective to teaching and understands the importance of showing students that it’s possible for a person in his position to succeed professionally.

“Even in my academic career, I was always excited by doing tutoring, outreach work and science demonstrations,” he said.

That enthusiasm was on display this summer as he conducted hands-on science experiments in his driveway for the children in his Castle Rock neighborhood.

“I sort of see the disability progression as a blessing in disguise because it did push me to a different path,” he said. “I’m really looking forward to teaching, and there is plenty of research to be done here as well.”