Talk about the weather

Here's how TV meteorologists are adapting to a rapidly changing media climate.

When the Weather Channel launched in 1982, Chris Spears was 4 years old and spending a lot of time with his grandparents, who were “absolutely hooked” on the nascent cable network.

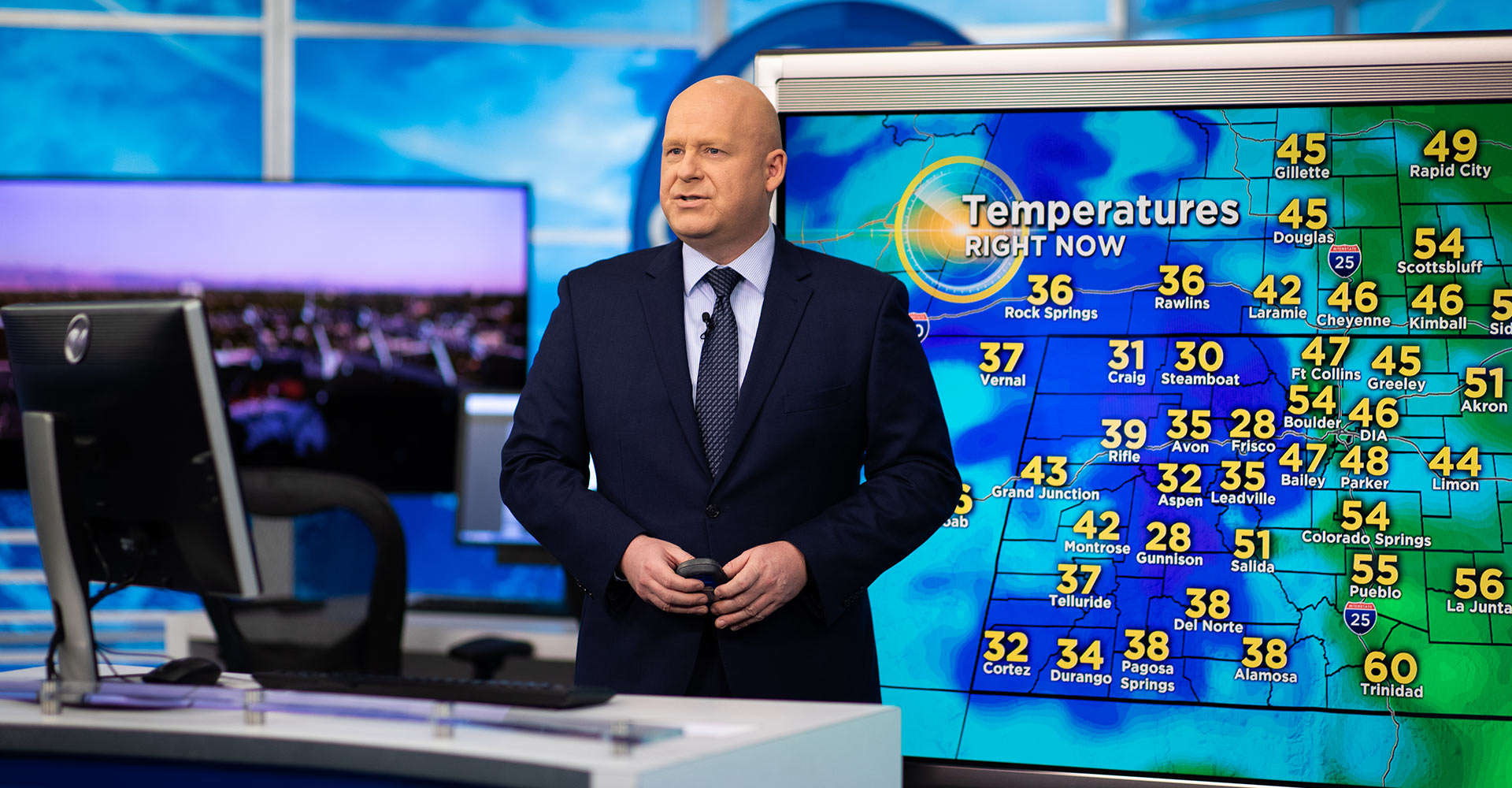

Soon, Spears (pictured above) was hooked too. The hours he spent watching weather reports with his grandparents sparked a lifelong passion for meteorology and forecast his own education and career path.

“I stood in front of the TV, pretending to do the weather,” recalls Spears, a 2005 meteorology graduate of Metropolitan State University of Denver and an on-air meteorologist with CBS4 in Denver. “I’ve been doing the weather since.”

It’s a familiar story for many meteorologists whose fascination with the weather began early in childhood and, in the case of Spears, eventually led to MSU Denver’s meteorology program. The program produced its first graduate in 1976 and has been churning out successful weather researchers, forecasters, educators and private-sector meteorologists ever since.

But few of those graduates are as well-known to the public as those who appear in our living rooms every morning, afternoon and evening preparing us for the next day’s sunny skies or storm threats.

“We are preparing students for all types of weather jobs, as well as grad school and research,” says Sam Ng, Ph.D., a meteorology professor in MSU Denver’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “But TV is just as important. People who go into television (meteorology) are scientists who have to be able to communicate their work to the public simply and clearly.”

Trust across platforms

The ability to build trust with viewers has always been a key to success for TV meteorologists, who, thanks to advances in forecasting, technology and computer modeling, can be timelier and more accurate than ever with forecasts.

But meteorologists say those advances also present challenges, as more viewers turn to social media and other online apps for weather information.

“Anyone can get a forecast in seconds on their phone,” says Matt Meister, chief meteorologist at Fox 21 in Colorado Springs. “But that doesn’t necessarily tell the whole weather story or the impacts – what the forecast means to daily life. So that’s what I’m focused on.”

Meister, a 2001 MSU Denver graduate, often engages with his viewers on social media (@TheWxMeister), answering questions and even offering advice to help them plan for vacations. Ultimately, meteorologists say they want to help people prepare for the weather and earn their trust, regardless of the platform.

Current snow totals this morning. Let me know what you’ve got! #cowx pic.twitter.com/taRw1nvcuC

— Matt Meister (@TheWxMeister) December 16, 2019

“This is a changing field,” says Dann Cianca, chief meteorologist at KION-TV in Salinas, California. “People are not always tuned in to traditional TV. With people continuing to move away, I try to use social media to reach people and pull them back to TV.”

Cianca, a Montana native and 2008 MSU Denver graduate, became fascinated with maps and the Weather Channel at an early age and soon after developed the passion he would pursue years later at MSU Denver. As he moved through his coursework, he got “a deeper appreciation of the science” and spent time “chasing storms” between classes. After his first job testing weather software for Meteostar in the Denver area, Cianca took his science skills to the television studio, accepting his first on-air job in Grand Junction.

“For a lot of people, TV meteorologists are the scientists they engage with the most. These are the scientists they see on a daily basis,” says Richard Wagner, Ph.D., a longtime climatologist, atmospheric physicist and meteorology professor in MSU Denver’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences. “They know a lot more than they can communicate to their audiences. Just having that scientific knowledge makes them better forecasters.”

The role of scientist – not television personality – motivates Alex O’Brien, a 2016 MSU Denver graduate and weekend meteorologist at KOAA-TV in Colorado Springs.

“It was really the science that brought me to meteorology,” she says. “Being on TV comes second.”

Growing up in Greeley, O’Brien took an early interest in storm observation and environmental science. She enrolled at MSU Denver for its undergraduate meteorology program, one of the few in the state that fulfills all the U.S. federal government civil-service requirements for classification as a meteorologist and the American Meteorological Society‘s recommendations for undergraduate meteorology programs.

O’Brien says the MSU Denver program – which includes a state-of-the-art computer weather laboratory and access to real-time weather data – prepared her for myriad jobs in meteorology or atmospheric science.

“I’d love to stay in broadcasting for as long as I can, but broadcasting and media are changing,” O’Brien says. “So, if I ever wanted to move on to something else in meteorology, based on my degree, I could. I have the credentials and knowledge to go into any sector.”

Jobs in the forecast

That’s good news for graduates entering a growing industry. Opportunities for atmospheric scientists, including meteorologists, are expected to increase by 8% over the next 10 years, with the best prospects coming in private industry, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

But the opportunity to explain and discuss complex meteorology in a way that will help their neighbors prepare for their daily lives is what inspires many who choose the broadcast path.

“I am a communicator and a nurturer by nature,” says Karissa Klos, a 2008 MSU Denver graduate and an on-air meteorologist at WeatherNation, a national weather outlet based in Centennial. “As much as I love the science, I knew sitting behind a desk for research or forecasting wasn’t ideal. I needed the human element.”

For Spears, that human element has expanded from the studio to the classroom. The CBS4 meteorologist is an affiliate faculty member at MSU Denver teaching weather and climate courses. Whether on campus or in front of a camera, his approach is the same.

“In every weather segment, I’m a teacher,” he says. “I’m trying to drop some sort of nugget that will help the audience better understand what’s happening. If you just rattle off technical terms, you’ve lost the audience.”

On-air learning

Spears and other MSU Denver graduates working in television markets big and small across the country say that in addition to completing an undergraduate meteorology program, internships are key to gaining important skills that will lead to on-air jobs.

Many MSU Denver meteorology students work on weathercasts for the student-run television station Met TV, while others intern for weather departments at local network affiliates, the National Weather Service, the National Center for Atmospheric Research and other Colorado-based weather organizations.

“Because I knew I wanted to go into broadcasting, the ability to intern in a top-20 television market was invaluable,” says Klos, who transferred to MSU Denver from a community college in Illinois. She landed back at WeatherNation after on-air stints in Iowa and Illinois.

WeatherNation has also been an important stop along O’Brien’s career path. She interned and was eventually hired as a producer there before landing her first on-air job in Lubbock, Texas.

“WeatherNation taught me the broadcast business while I continued to work on my on-air skills,” she said. “That’s not something that comes naturally.”

But it becomes easier with more experience, says O’Brien, who’s happy to be working in her home state at KOAA-TV. She and others who went through MSU Denver’s meteorology program say the University’s location on the Front Range is an ideal training ground for learning about severe weather.

“Colorado and the Front Range is one of the best places to forecast. It keeps us humble,” says Meister. “Other than hurricanes, we get everything else. It’s a great place to practice meteorology, and it’s a great place to learn meteorology.”