7 learning myths debunked

Want to make sure your schooling sticks? Spoiler alert: Listening to Mozart won’t help.

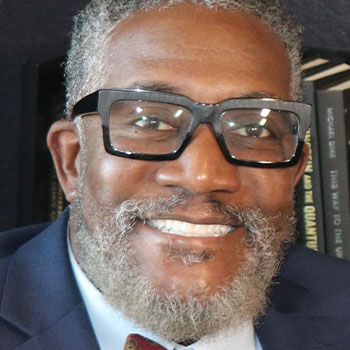

Theories about the best way to learn abound in the world of education – but many continue to circulate in classrooms or through product marketing, even though they’ve been disproved by scientific research. Whether you’re prepping for the fall semester or sending your tyke off to kindergarten for the first time, take a guided tour through some of academia’s enduring learning myths with Aaron S. Richmond, Ph.D., professor of educational psychology and human development at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

1. Multitasking

While popular for a time, this learning approach was fatally undermined by a single flaw: People really stink at multitasking. Most of the time when we think we’re doing it, we are actually task-switching – moving quickly between one task and another, Richmond said. As a learning tool, the approach always had limited use simply because we are not good at focusing on different things simultaneously.

This point was demonstrated by an experiment that compared drunk drivers with texting drivers, he explained. It found that the drink-impaired drivers performed better behind the wheel because they were focusing on the road. The perfectly sober texters, meanwhile – trying to drive and send a message at the same time – got into all kinds of trouble.

2. Brain-based theories

Back in the 1990s, you often heard people describe themselves as primarily “right-brained” (good at math and logic) or “left-brained” (creative) thinkers, Richmond said. In those days, students were also confidently assured that they were using only 10 percent of their brain – which of course implied that everyone had vast reserves of unused potential and intelligence.

Ironically, both of these theories had nothing to do with learning, he said. They originated from a couple of psychology studies that exploded worldwide because what academics call their “seductive details” made for such good copy. Essentially, they were psychological clickbait. As for their validity? It’s complete nonsense. We know from neuroscience that we use all of our brain – on both sides.

|

Here’s what good learning looks likeAn ideal learning experience should include these four qualities: Adaptive and flexibleRegardless of the subject – philosophy, art, biology – being taught, good learning approaches should apply to a wide range of circumstances and needs. MultimodalFor information to truly sink in (whatever the subject), it should ideally be communicated visually and aurally – and even experientially, if possible. RepetitiveFew things are learned in an instant, so students need learning points to be reinforced in multiple sessions over time. Meaningful and personalWhen educators can link learning topics to something personal in their students’ lives, everyone does better.

|

|

3. Learning styles

Imagine you set the dinner table every day for three children and give one child a fork, another a spoon and the third just a knife. Ravenously hungry, the kids would make sure they got the food down somehow. Then a month later, you announced: “See? Clearly, Pedro prefers to eat with a fork, Yolanda likes a spoon, and Johnny is all about his knife.”

Welcome to learning styles: the theory that students accumulate knowledge best if taught exclusively using a particular method (such as visual, auditory or kinesthetic), rather than employing all their skills and senses. Learning styles have repeatedly been exposed as a “neuromyth,” fueled more by educators’ preconceived beliefs than their students’ needs, Richmond explained. And yet they remain hugely popular: More than 80 percent of Americans still vouch for them, he said.

4. Listening to Mozart makes you smarter

When it comes to terrible educational theories, the 1990s have a lot to answer for, Richmond said. This particular theory originated with a small psychology research project in 1993. (And it’s worth noting that the original research explicitly did not make any claims regarding the composer’s brain-boosting power.)

But hey, the idea was too catchy to ignore. And ever since, “The Mozart Effect” has been unendingly marketed in hundreds of books and CDs and countless other products that confidently promise to raise student IQs by a few octaves, he said. There was a potential blip on the radar in 2010, when the University of Vienna analyzed nearly 40 follow-up studies on the theory and found zero correlation between listening to Mozart and “enhanced” cognitive abilities. But of course, by then nobody was paying any attention.

5. The theory of multiple intelligences

In 1983, Harvard Professor Howard Gardner suggested that traditional notions of intelligence were too limited and proposed eight types of intelligence (including fun-sounding categories such as Spatial, Musical and Naturalist) that might better harness children’s potential. The basic idea was to find the type of intelligence that best complements a student’s particular gifts, allowing them to flourish. Richmond said.

The fundamental issue with this theory, apart from its complete lack of empirical evidence, is that it encourages students to focus on certain strands of intelligence at the expense of all others, he explained. It’s like going to the gym every day and only doing biceps curls with your right arm, while everything else atrophies. Also, the approach provides an easy out. If a student is not doing well academically, they can always say, “Well, you see, I’m mainly a musical learner.” And ultimately, that doesn’t help anyone.

6. Gender dictates aptitude at certain subjects

Boys prefer math and science, while girls are good at arts and languages – right? No, not even close, Richmond said. Thousands of studies have painstakingly explored male and female aptitude across a wide range of subjects and overwhelmingly found no difference. A single disparity is that boys in eighth grade tend to do a little better than girls at math, but that’s likely because educators’ cultural bias kicks in when teaching male students at that age.

Unfortunately, this myth persists throughout school and continues well into college, where even today young men and women are shuffled toward hard science and softer social subjects respectively, Richmond said. But it’s important to remember that this is all about societal pressure. It has nothing to do with student aptitude.

7. Raising self-esteem improves academic performance

This educational theory from the 1990s had the best intentions: to make students feel great about themselves and so yield better results from them, Richmond said. Unfortunately, the exact opposite happened. Basically, the approach set students up to fail by heaping heightened expectations upon them – because if teacher says you’re doing just great and you still flunk the test, your fall is all the harder.

Today, educators focus not on self-esteem but self-efficacy, which centers on a person’s belief in their ability to succeed at specific tasks, he said. (For example: A person that is 5-9 and weighs 190 pounds can say, “I don’t have a strong sense of self-efficacy that I can dunk a basketball.” However, that same person – can say, “I am confident that I can write a very good research paper.”) In some ways, believing in your ability to succeed at challenging goals can put you on the road to achieving them.