What makes you angry?

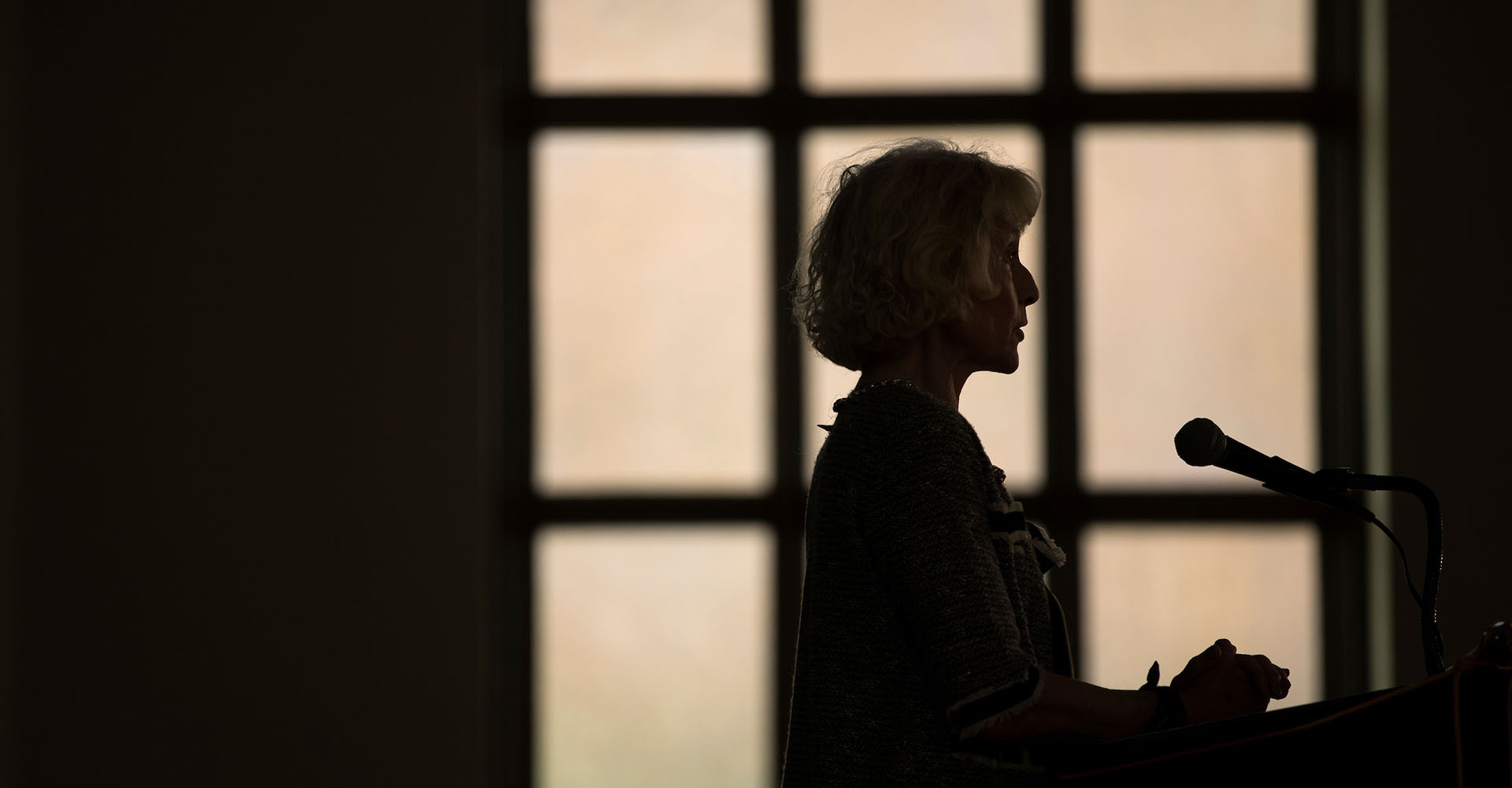

Distinguished thinker Martha Nussbaum discusses the origin of anger and disarming the politics of blame.

Anger is seemingly everywhere.

One of the basic human emotions, it manifests in many forms. But what is easy to dismiss (or succumb to) as blanket rage is a deeply rooted sentiment at the very essence of humanism – and one we’ve been wrestling with for a long time.

Take the case of the Furies. At the end of Aeschylus’ “Oresteia,” a transformation happens when the goddess Athena helps instill a court of law to replace the system of blood vengeance that had previously ruled the land.

This eye-for-an-eye practice had been driven by three primeval spirits portrayed as unbridled anger who would torment wrongdoers as a form of retributive justice. As the story goes, they’re incorporated into the new judicial practices by being given a place of honor beneath the Earth and harnessing their powers for collective good.

“If you read the Greek historians and orators, you see some things that are pretty familiar,” said Martha Nussbaum, Ph.D., the Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago and internationally renowned thinker.

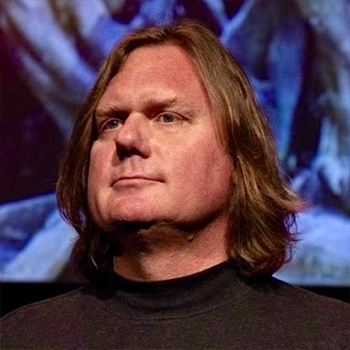

“Individuals litigating obsessively against people that they think have wronged them, groups blaming other groups for their relative lack of power, citizens blaming prominent politicians and government elites for selling out the democracy, other groups blaming foreigners or even women for their own political and personal ills,” said Nussbaum, who was introduced by former U.S. Sen. Gary Hart to a packed crowd for a recent Denver Project for Humanistic Inquiry event.

“Like modern democracies,” Nussbaum said, “the ancient Greek democracy had an anger problem too.”

As evidence, Nussbaum detailed the ancient civilization’s judicial evolution as recounted in the Greek tragedy above.

However, she also detailed how Athena’s persuading the Furies to join the political enterprise showcases a second form of transformation – one that alters the fundamental element of an anger-driven identity in exchange for constructive inclusion.

This laid the groundwork for the argument in favor of understanding and moving to an attitude of protest honoring lived experience without payback as its engine.

“Anger pollutes democratic politics and is of dubious value in life and the law,” Nussbaum said. “It’s all the worse when it’s fueled, as it so often is, by a working fear and a sense of helplessness. But that idea is radical in America and evokes strong opposition – for anger, with all its ugliness, is a popular emotion.”

To make this case, Nussbaum presented six segments of philosophical argumentation to support why operating from a position of anger is fatally flawed from a normative perspective, incoherent and based on bad values, and deflects from real problems by seizing powerlessness.

The roots of anger can be traced back to a fear and vulnerability felt as a helpless newborn; Roman philosopher Lucretius did just this, connecting the political ills we face today with that same fear and helplessness. However, once we gain causal thinking, fear takes the next step of attribution – “someone caused me this pain.”

This feeds into an Aristotelian definition of anger, as a painful emotion that responds to perceived significant damage to something or someone cared deeply about, and the damage the angry person believes to be wrongly inflicted, coupled with payback. Nussbaum highlighted the ability to transcend this inclination, pointing to parents suspending harsh discipline of a child as a mitigated reaction of this impulse.

Such a distinction is important for several reasons but significantly because of the potential for errors in judgment and a backward-facing orientation; it’s also counterintuitive to our love of an orderly universe and attraction to simple truths, Nussbaum said.

“The act of pinning blame and pursuing ‘the bad guy’ is deeply consoling,” she added. “It makes us feel in control rather than helpless.”

Which leads to the idea of anger being a child of fear – but also inextricably linked to other human emotions. The Stoics proposed abandoning goods of fortune as a way of jettisoning fear and, by proxy, anger – along with other aspects of humanity, however.

“The problem is that losing fear also means losing love as an attachment to someone or something outside of your control,” Nussbaum said. “Keeping love means keeping fear.

With the intractability of these experiences, the shift is then to keep a spirit of determined justice without a strategy of payback. Nussbaum highlighted the work of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela as examples of productive results of a rising surfeit of anger.

“A central idea shared between (them) and Aeschylus is that courage is required to face a problem – that lashing out leads to a spiral of violence,” Nussbaum said. “We can refuse payback while still looking to the the future with hope and justice.”

Which takes us back to (the future of) ancient Athens.

By using the tools of rhetoric and compassion, Athena necessarily transformed the rage of the Furies from a destructive, obsessive nature into a contributive framework, fed by tenets of justice and accountability.

“Unchanged, (they) could not be at the foundation of a legal system devoted to the rule of law – you don’t put wild dogs in a cage and come out with justice,” Nussbaum said. “They had to adopt a new range of sentiments, substituting future-directed benevolence for past-directed retribution.

“Perhaps most fundamental of all, they had to learn to listen to the voice of persuasion.”