Running the road to health-care breakthroughs

Across four decades and two continents, MSU Denver graduates are shaping global health care through their work at Johns Hopkins

In many ways, the human body is like an automobile. Both need fuel to run properly, come in all shapes and sizes, and tend to wear down with age. Both are systems with many parts working together, where one weakness in the system can bring the whole to a halt.

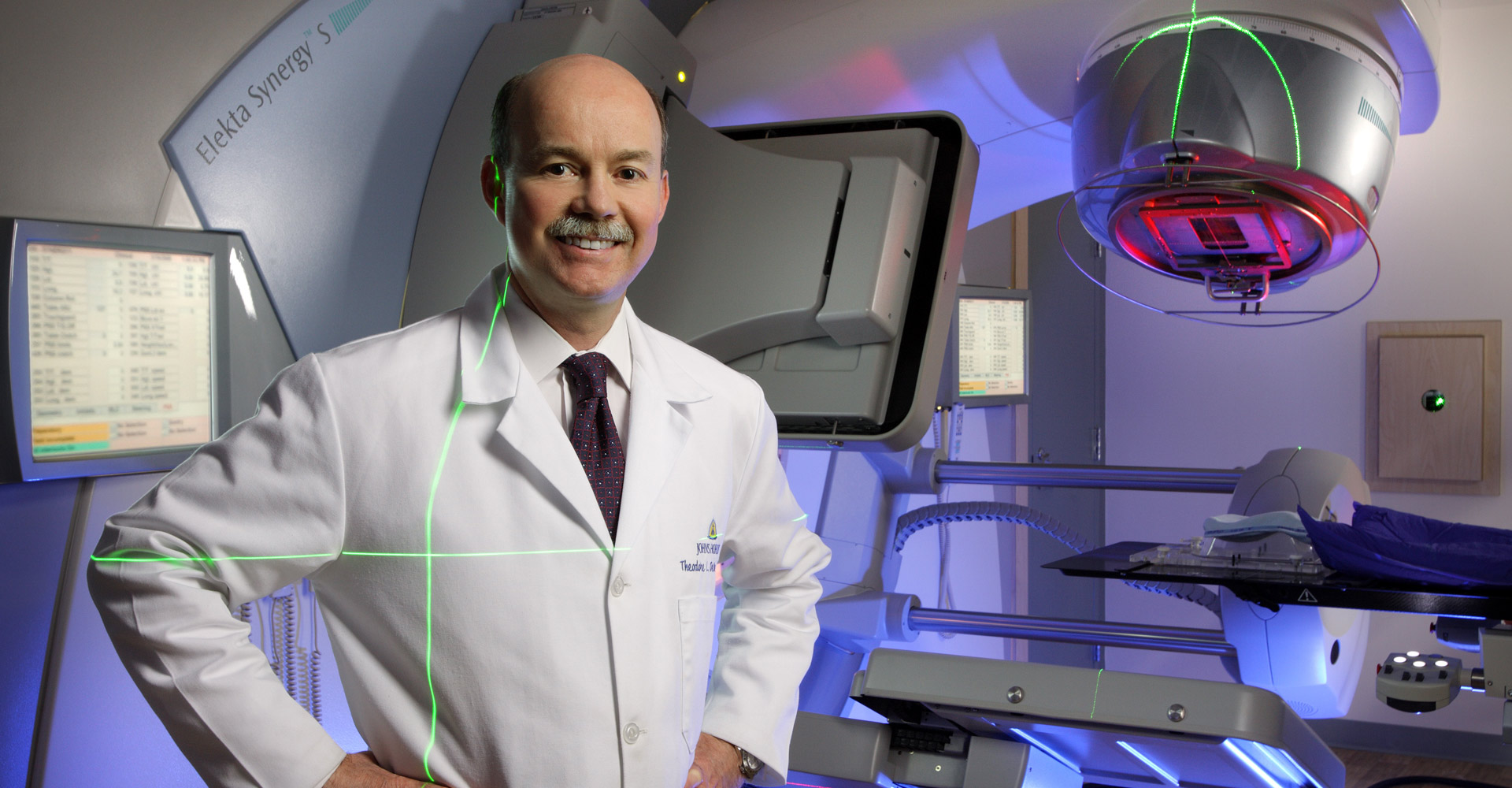

Dr. Theodore DeWeese, vice president of interdisciplinary patient care for Johns Hopkins Medicine and chair of the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular Radiation Sciences, could explain both ends of that analogy better. Well before DeWeese had a long job title at the Cadillac of medical schools, he spent several years working as an auto-parts clerk and mechanic at the O’Meara Ford dealership in Northglenn.

DeWeese’s path from sourcing and fixing radiators to finding new radiation treatments for cancer patients started with a handful of accounting classes at what is now Metropolitan State University of Denver. No one in DeWeese’s family had ever gone to college, but his mother told him he was smart enough for it without pressuring him to go right after high school. A few years after graduation, he took some night classes and became certain that he wanted to go to school full-time – and that he had no interest in accounting.

“To graduate from the college, you had to have a science credit. I wanted a chemistry set growing up, and my mother never let me have one, so I took Intro to Chemistry. That class and Professor Fred Dewey changed my life,” DeWeese says.

A first-generation student who came to college with no confidence, no idea what he wanted to do and a course load including remedial math graduated magna cum laude in 1986 with a degree in chemistry, a minor in biology and a path to medical school.

“I rolled the dice. No one in my family had been to college, much less medical school. That seemed like such a reach,” DeWeese says.

DeWeese found med school at the University of Colorado within his reach, and then a residency at the prestigious Johns Hopkins University. He planned to return to his home state after that but was offered a laboratory fellowship by Johns Hopkins and then a faculty position in 1995. He is now a full professor in three departments and is the Sidney Kimmel Professor of Radiation Oncology. It’s safe to say the fine folks at the Ford dealership north of Denver didn’t receive a reference check.

In 1999, the former parts counterman and sometime mechanic and his colleagues devised the first adenoviral gene-therapy trial for prostate cancer. They manipulated a common-cold virus – which is evolutionarily designed to infiltrate cells, replicate and then kill the host cells on its way out – to target prostate-cancer cells specifically while leaving normal cells unharmed.

“I treated the first human in the world with that. I was scared to death. It was so exciting and nerve-wracking, but it did work, and we could document and prove it,” DeWeese says.

DeWeese was named the inaugural chair of the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular Radiation Sciences at Johns Hopkins in 2003, and his department has grown tenfold in the years since. When he added a vice-president title in 2016, he was charged with coordinating the development and quality assurance of interdisciplinary-services lines across the many affiliates of Johns Hopkins Medicine – the medical school, six hospitals, four insurance companies, a home-care group and various other entities.

Despite multiple roles and high-level strategic planning, DeWeese still makes time to run the grant-funded research lab he started more than two decades ago, and his team has a new clinical trial written for an even more efficient prostate-cancer treatment based on injecting DNA that makes cancer cells hypersensitive to radiation or chemotherapy.

“Discovery is the basis of everything we do,” DeWeese says. “If we’re doing the most contemporary research, it translates directly to the most contemporary care of patients.”

Social work for the soul in Saudi Arabia

Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare is a first-of-its-kind joint venture between Johns Hopkins Medicine and Saudi Aramco, the global energy titan that is reportedly the world’s most profitable company. Saudi Aramco’s long-established health-care system provides care for the company’s employees and their beneficiaries, who number about 360,000.

The partnership, announced in 2014, provides enhanced services, new lines of treatment, research and education that address some of the most significant health-care challenges in the region.

Long before the United States’ first research university established a presence in the Middle East, Hikmat Zughabi was overcoming her own challenges in the U.S.

Zughabi immigrated to Colorado from Saudi Arabia in the 1980s. She enrolled at MSU Denver and worked two jobs so she could escape an abusive husband and provide a place to live and a future for her three sons.

Inspired in part by her own family’s struggles, Zughabi pursued a career in social work and graduated with a degree in behavioral science in 1995 before moving back to Saudi Arabia to take care of her mother.

“I struggled for some semblance of independence and to get myself to a safe space. When I look back, I don’t take my education or my independence for granted,” Zughabi says.

Her perspective is unique in a country that just granted women the right to drive in June.

Zughabi took a job as a social worker at Saudi Aramco’s Dhahran Health Center and eventually Johns Hopkins Aramco Healthcare, where she provides counseling and ongoing support to help patients and their families work through mental- and emotional-health issues that stem from stressful life events such as chronic illness, grief, loss, depression, family conflicts, abuse or cultural differences.

In her 21 years in the Aramco health-care system, Zughabi has helped establish child life programs, cancer-support groups, survivor volunteer networks and patient-education programs.

“I have worked on-call as a 24-hour crisis-response social worker taking care of people in their darkest hour. Children I supported over 20 years ago have expressed gratitude as adults for the impact I made in their lives,” Zughabi says. “What I am most proud of is leaving a positive impact on the people I care for.”

A policy of helping people

John Hagenbrok arrived in Washington, D.C., with degrees in health-care management and political science, a girlfriend (now his wife) he met on the Auraria Campus and a desire to influence health policy by drafting legislation and working with lawmakers.

The 2009 MSU Denver graduate interned with a congressman in Washington before shifting to the provider side of health care by joining Johns Hopkins Medicine as a project manager.

“My education really taught me to think more holistically about problems and understand the big picture,” Hagenbrok says. “I wanted to touch people’s lives. I thought learning management, business principles and how to apply some of that in the field of health care would achieve a higher purpose.”

Similar to DeWeese’s work on interdisciplinary patient care, Hagenbrok’s team works on process improvement to find efficiencies and help Johns Hopkins best leverage its resources. The two Roadrunners had even worked on some of the same projects without knowing they shared an alma mater until recently.

For both men, the whole reason they came to Johns Hopkins is to provide as many people as possible with the best possible health care.

“At the end of the day, we’re not working with widgets; we’re working with people,” Hagenbrok says. “What’s at stake is the quality and quantity of people’s lives. Regardless of who you are or where you’re from, we all share one trait, which is our health.”

Research. Innovate. Repeat.

Thirty years after DeWeese graduated from MSU Denver with a degree in chemistry and a future at Johns Hopkins ahead of him, Kenneth Marincin did the same.

As an undergraduate, the 2016 alumnus helped design a laser spectroscopy lab, conducted undergraduate research on biodiesel production from waste oils and learned how to apply quantum mechanics to physical chemistry.

Marincin is now a graduate researcher in the Molecular Biophysics Program at Johns Hopkins University, studying how various peptide-based products are made without DNA instructions – like building a perfect building without blueprints. These peptides can be modified to become other molecules that serve as antibiotics or have other medical uses.

“One thing for me that is at the core of scientific research as a whole is I felt that the research I was doing needed to lead to beneficial advancements in that field. Hopkins gives its students the tools and resources needed to pursue this objective,” Marincin says.

He plans to complete his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins and go wherever his research takes him, whether it be academia or industry.

“I always dreamed of going to Johns Hopkins. They are at the forefront of groundbreaking biological and clinical research,” Marincin says. “This is a great university to truly make a name for yourself in the scientific community.”