A U.S.-China trade war will hit your pocket

The world’s two largest economies are threatening each other with billions of dollars in tariffs. We might all pay, an Economics professor says.

Trade disputes, like a spark catching in a summertime forest, can quickly grow out of control.

A month ago, President Donald Trump announced a series of new tariffs on imported steel and aluminum. China soon responded with retaliatory measures. Since then, the world’s two largest economies have become embroiled in an escalating exchange of tit-for-tat tariff threats that amounts to hundreds of billions of dollars.

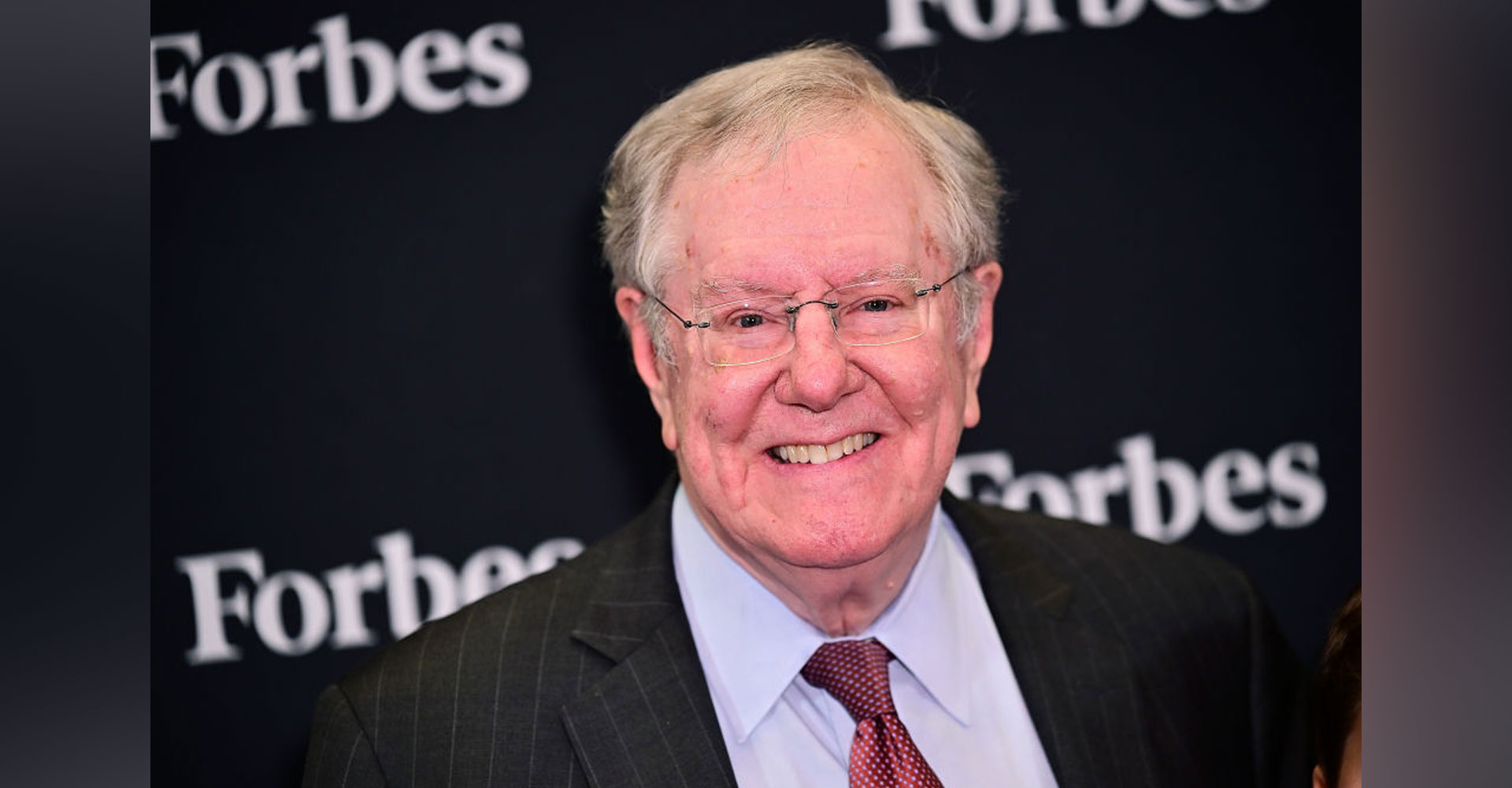

So where does this global-level game of chicken leave the rest of us? Alexandre Padilla, Ph.D., associate professor of Economics at Metropolitan State University of Denver, digs beneath the tough talk and posturing to provide a few hard facts.

Trump said, “Trade wars are good and easy to win.” Discuss.

Basically, trade wars are political tools used to please interest groups that have political power — whether that be domestic industries, unions or voting groups. And tariffs are nothing more than taxes imposed on foreign goods. Countries use them to make foreign products artificially less competitive and thus promote domestic producers. But tariffs inevitably lead to increased costs for consumers, so even when you “win” a trade war, you actually lose.

Trump argues that we need to respond against China’s blatant stealing of American technology and large-scale cyber-crime. He has a point, hasn’t he?

Kind of. President Trump’s argument that China does not respect U.S. patent laws and trade-secret laws is true. But the question is whether engaging in a trade war is the proper way to dissuade them, since the losers will be not only Chinese producers but also American consumers and businesses. And besides, let’s not be naïve: The U.S. also engages in industrial espionage.

How worried should American consumers be about getting hit with rising prices in the near future? What kind of goods might be most affected?

Average American consumers will be big losers in a trade war, even if the tariffs are aimed primarily at intermediary business products rather than directly at domestic goods. Why? Because businesses tend to pass on their extra costs. Take aluminum and steel, for example. While most Americans don’t actually “consume” these materials, we all buy plenty of goods made from them. So if the price of producing a beer can, say, suddenly increases, there’s a good chance the beer industry will ultimately pass on that cost to consumers. Similarly, if agricultural equipment becomes more expensive — increasing production costs for farmers — you’ll probably feel the impact at your local grocery store somewhere down the line.

Such national confrontations can quickly escalate into an all-out trade war. Behind the posturing and harsh words, what is each side realistically hoping to achieve?

To be honest, I think this is again Trump being Trump. After all, he ran his campaign on protecting U.S. interests, whether it be in the realm of trade or immigration. But if the president and his current administration are hoping to strong-arm China into opening their borders and allowing more U.S. investment and imports, they should maybe learn a little more about history first. China is not going to give in to foreign influence. The U.S. has tried this since the 19th century, and it hasn’t worked.

Tariffs are a very blunt instrument. What might have been a better course of action for the president to take?

I recognize it’s difficult for him from a political viewpoint, but the better course would really have been to do nothing. Using tariffs to artificially reduce competition has been tried many times before, and the outcome is always the same: protection (though only temporary) for a relative minority of domestic producers and raised costs for other consumers. Of course, free trade is far from perfect, and all too often, hardworking people lose their jobs to overseas competitors. But the government should help those people through new skills training and by expanding the safety net. Tariffs aren’t the answer.

This whole skirmish started with the U.S. government imposing steel and aluminum import tariffs. But we have now exempted Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, South Korea, Australia and the European Union, which means more than half of all U.S. metal imports will remain tariff-free. In which case, what was the point?

This action is all about appeasing the fears that some voters have about China. Many people believe that China is the new “enemy,” as the U.S.S.R. was during the Cold War. And if that country is now the cause of all our ills, well, then the government should do something about it! Again, this is purely a political, not economic, decision. And a quick reality check: China’s exports to the U.S. only represent about 3% of their total exports, so it’s really not that big a deal for them. But because the average voter doesn’t know this, the president’s tough talk on tariffs gives the appearance of aggressively looking out for U.S. producers’ best interests.

Political strategist Mark McKinnon famously said of tariffs: “No one ever wins, and consumers always get screwed.” Given that historical context, how do you see the endgame playing out here?

He pretty much got it right, I’m afraid. It’s possible that a few U.S. steel and aluminum producers will gain from these actions, but it’s difficult to see how those meager benefits will outweigh the costs of millions of consumers losing out. That’s why virtually all economists disagree with this policy decision — we’ve seen it before. Like many politicians before him, President Trump came into power making bold political promises. And now he is learning that, particularly when it comes to economic decisions, you simply can’t ignore how the markets and other market participants might react to your policies. Today, there is a sense that this situation could start unraveling at any point. And as history has repeatedly shown, if a full-blown trade war does break out, nobody will win.