Partnership addresses Colorado’s water challenges

MSU Denver and the Denver Botanic Gardens want people to care about water conservation.

Growing up in the high desert, water awareness and basic habits of conservation became a way of life for MSU Denver student Blake Collins.

In his formative years, he remembers water restrictions and was taught to turn off the tap when washing dishes. He learned to carry sufficient hydration when mountain biking in the desert, which became his passion.

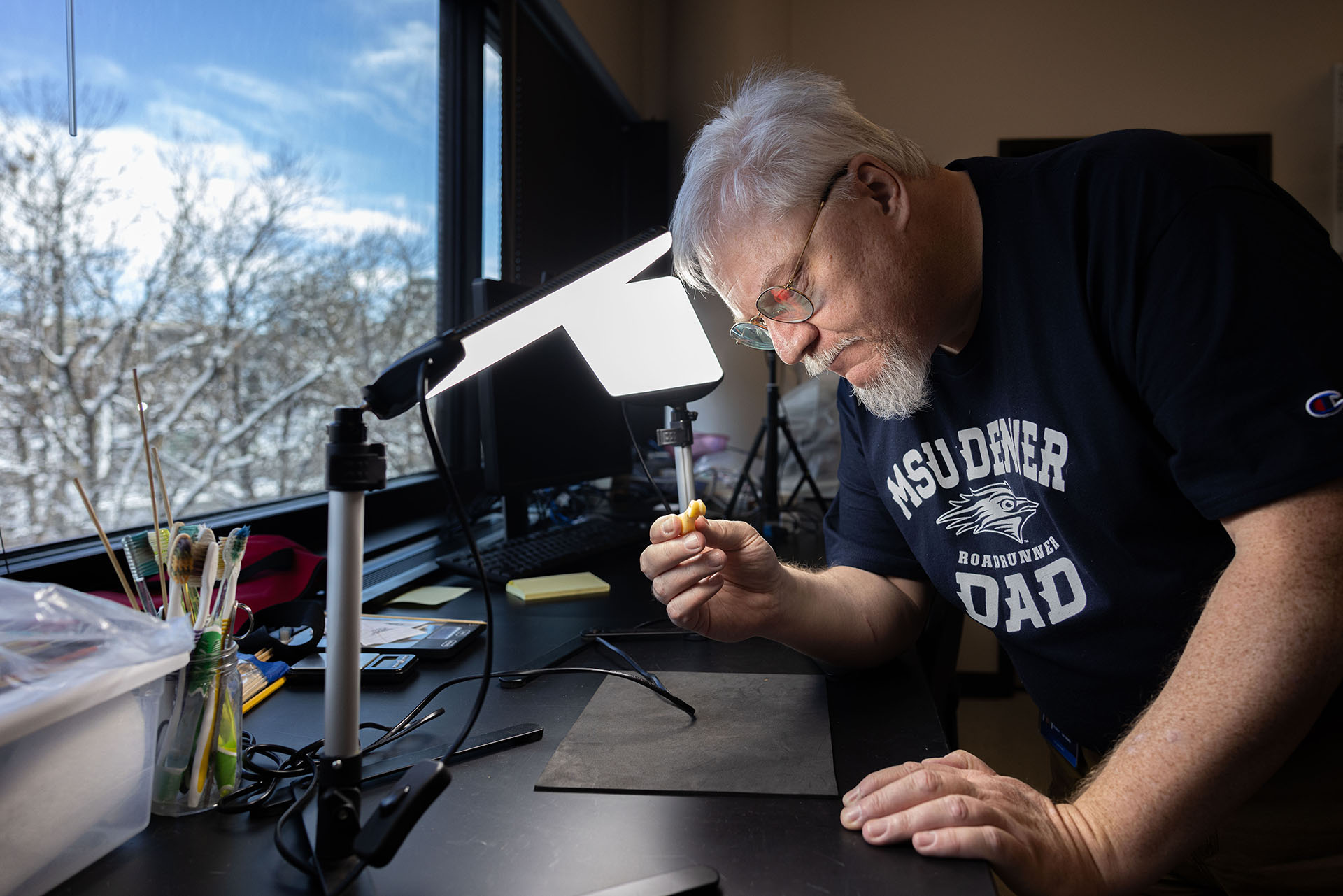

Now, Collins, 28, is a senior biology major with a water studies minor at Metropolitan State University of Denver. In addition to working part time as a bike mechanic in Denver’s Highlands neighborhood, he serves as one of the first two paid interns as part of the One World One Water (OWOW) Center for Urban Water Education and Stewardship. The center was launched in 2011 with an anonymous $1 million grant. It is now a collaboration between MSU Denver and the Denver Botanic Gardens.

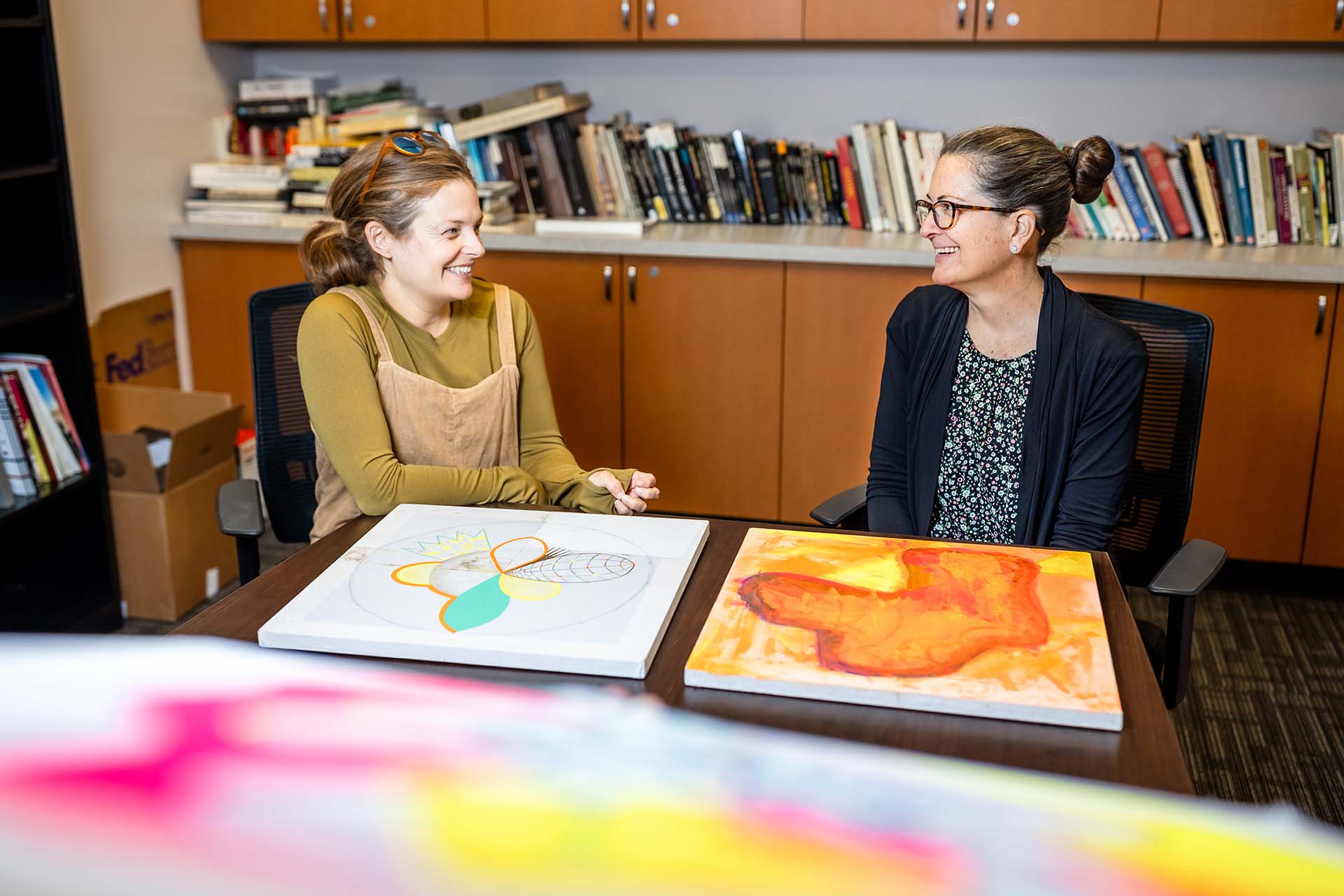

Jennifer Riley-Chetwynd, director of marketing at the Denver Botanic Gardens and instructor in MSU Denver’s water studies minor, is excited about OWOW’s potential. Water will always be the nucleus of this relationship,” she said. “The Denver Botanic Gardens has a long-standing commitment to showcasing and educating about water-wise landscaping. But in order to get people to care about that, you first have to get them to care about water. MSU Denver and the gardens have a great opportunity to raise water IQ – with students, gardens members, the general public.”

Presently the Denver Botanic Gardens is funding two internships per semester for MSU Denver students. “I want to establish some continuity between the gardens and MSU Denver in terms of projects that students can plug into, said Riley-Chetwynd. “Being able to leverage the broad base of knowledge that OWOW minors develop while at MSU Denver is a huge plus for the gardens.”

The OWOW Center aims to attract funding for joint research related to water and environmental issues, and to enhance water stewardship on and beyond campus. Through three academic programs — a water studies minor, water studies certificate, and a water studies online certificate — the center is achieving its goal to expand the reach and breadth of educational programs on water and environmental issues.

Collins and Riley-Chetwynd met last spring, when he was a student in her journalism course, Covering the Environment. “Seeing how passionate she is about her subject drew me in. It was captivating. It was different and new. And the students in the class all brought different backgrounds, depending on their main areas of study.”

MSU Denver’s multidisciplinary water studies minor includes courses from geography (Global Water Concerns) and environmental studies (Water Resources), to management (Colorado Water Law and Water Rights Administration) and the College of Arts and Sciences (Water Conflict).

Riley-Chetwynd will teach her course for the fifth time next spring. “Students spend a semester thinking about who is talking about water issues, how they are talking about them, and how are varied audiences responding to the information. Not everyone who takes the course will become a journalist, but I hope they’ll graduate to take on roles that influence what others think about water issues—as teachers, lawyers, scientists or in other fields.”

Riley-Chetwynd will teach her course for the fifth time next spring. “Students spend a semester thinking about who is talking about water issues, how they are talking about them, and how are varied audiences responding to the information. Not everyone who takes the course will become a journalist, but I hope they’ll graduate to take on roles that influence what others think about water issues—as teachers, lawyers, scientists or in other fields.”

Now in his final semester as an undergraduate student, Collins is supporting the fluid movement of ideas between MSU Denver and the Denver Botanic Gardens, rather than counting benthic macro invertebrates for an environmental consulting firm, which was his initial internship option. Looking ahead to December, when he graduates, he hopes to create a business or work within a profession that combines recreation and conservation.

“I always say, if you enjoy the outdoors, then you’re an environmentalist,” said Collins, who studied biology, botany and zoology at Red Rocks Community College before transferring to MSU Denver. “When I go to Moab, I’m aware of water’s scarcity. It’s ephemeral. It shows up, and it can be gone. We need water to do anything in terms of growth, and we’re running out of ideas for supply,” said Collins.

Whatever Collins does, he will apply the critical thinking skills he learned, especially when examining the way environmental issues are covered in the media. “Things aren’t black and white, especially in conservation,” Collins said. “Not just about water. Take oil and gas, for example. How are we getting it out of the ground? How are we moving it? To get beyond knee-jerk reactions, both sides need to recognize the gray scale.”