Remembering Denver’s deadliest riots a century later

Historian Steve Leonard explains why the August 1920 Denver Tramway strike remains relevant today. PLUS: Archival images show how the protests brought the city to a standstill.

The stage was set for unrest: A pandemic was ripping through the population, unemployment was soaring and racial and economic inequities were deepening. When protests demanding change turned violent, federal forces intervened.

While it might describe this summer, these were the conditions in Denver in August 1920 – exactly a century ago – and the strife led to a strike by Denver Tramway Co. workers that turned deadly.

“The Denver Tramway Strike of 1920 mired the city in gridlock,” said Steve Leonard, Ph.D., professor of history at Metropolitan State University of Denver. “It was like a Greek tragedy, set to play itself out.”

On the 100th anniversary of the conflict , RED caught up with Leonard to learn more about the strike and its parallels to what Colorado is experiencing in summer 2020.

What happened in early August 1920?

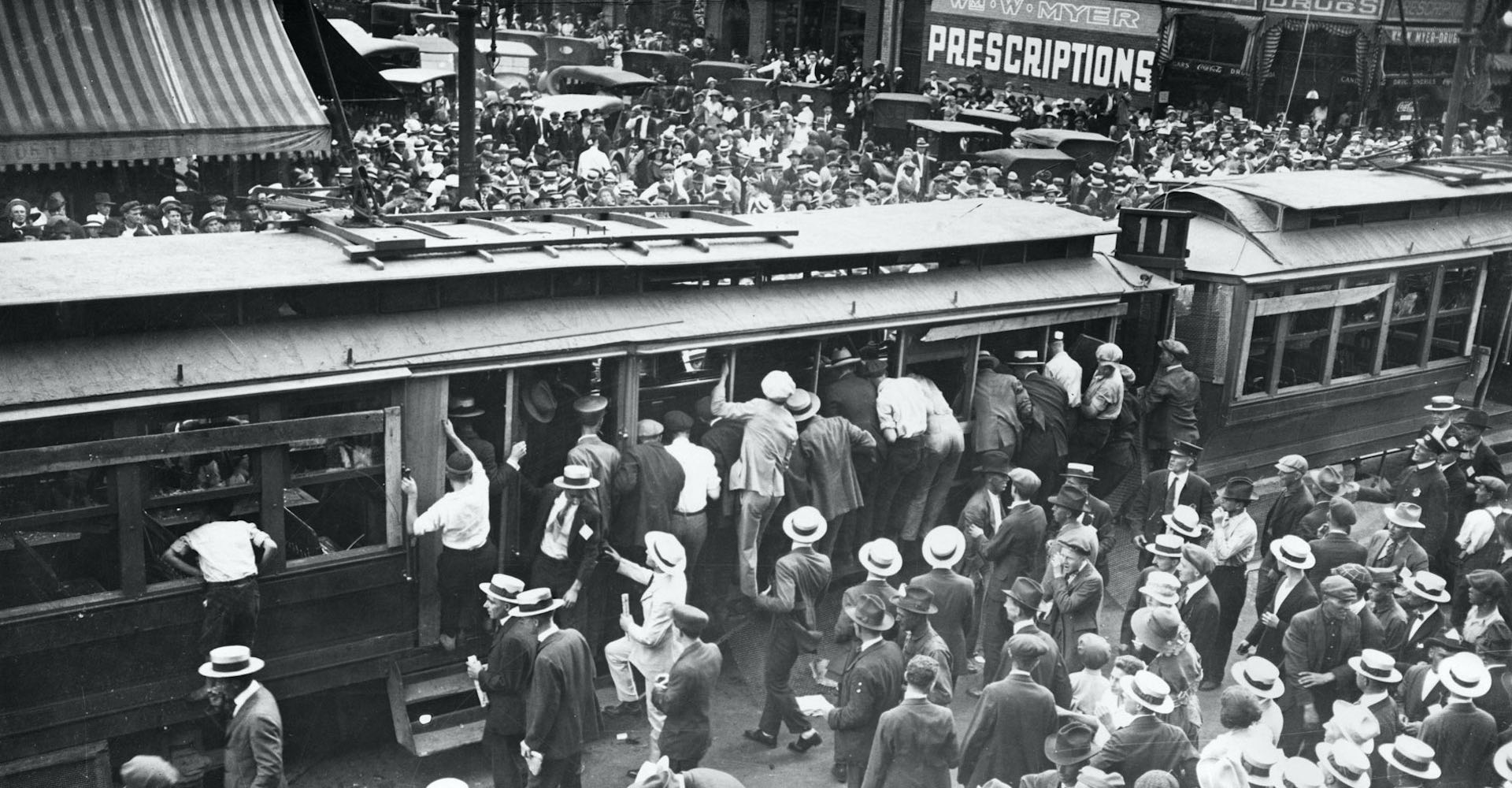

SL: After seeing their wages eroded by high inflation during World War I, Denver Tramway Co. workers went on strike for higher pay on Sunday, Aug. 1, 1920. The company, anticipating a strike, had already brought in John “Blackjack” Jerome, a successful strikebreaker, who hired hundreds of strikebreakers to replace the unionized workers.

An increasingly chaotic week of confrontation followed. By late Friday, Aug. 6, seven people had been fatally shot by panicky strikebreakers who felt threatened by union sympathizers. Union leaders disavowed violence as counterproductive, but there likely were strikers and sympathizers who disagreed, along with those just looking to make mayhem.

The chaos ended on Saturday, Aug. 7, when Denver’s mayor and Colorado’s governor requested federal intervention. U.S troops disarmed the strikebreakers and protected them as they drove. That reinforced the power of Tramway owners, and the strike ended without any concessions for the workers.

How did economic inequality contribute to the conditions faced in 1920?

SL: Denver certainly had its divisions between those well-to-do and the large number of folks struggling in the post-World War I economy. One of the greatest fears of the upper class was the potential of something similar to the ongoing Russian Revolution playing here in the U.S.

That led to a tremendous fear of the working class, sharpening tensions between capital and labor that had been going on in Denver for decades.

What was public sentiment like at the time?

SL: It was mixed. The Denver Post, which was far and away the most powerful paper at the time, was very much on the side of Tramway, which influenced perspective; you did, however, have a large number of pro-union supporters as well. Eventually, you saw the population essentially call a truce on this issue, but some went on to take advantage of the underlying social fear that had been set in motion.

How did this contribute to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in Denver politics during the 1920s?

SL: In 1921, some Denverites formed an organization called the Denver Doers Club. It was essentially the Klan in disguise. Within a couple years, the Klan emerged as a major political force in Denver and Colorado.

The Klan had “law and order” as one of their major themes – one that resonated with many people because of the strike chaos. The Klan was playing upon people’s fear of Black people and of other groups such as Catholics and Jews, who were looked upon as dangerous to the established order. In their “law and order” stance, the Klan found a way to justify and sugarcoat their bigotry.

What takeaways can we apply from the 1920 Tramway strike to today?

SL: As a society, we are experiencing incredible strain right now, and how things play out is difficult to tell. Over time, history has a way of confounding those who make predictions.

Take, for example, Gerald Hughes, a wealthy Denver financier who backed the strikebreakers. Today, this once-powerful banker is largely forgotten. Some of his wealth wound up supporting the Denver Dumb Friends League. A hundred years on, the battles between financiers and Tramway strikers have been washed away and, in a strange twist of fate, have contributed to happy animals in 2020.

I guess that goes to show for every action there’s a reaction we can’t fully predict and that good can unexpectedly come out of bad and challenging times – that’s part of what makes history so compelling.