Whale tale

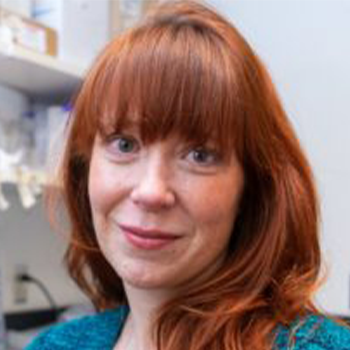

MSU Denver biologist Leanna Matthews is featured in Apple TV’s new documentary 'Fathom,' which explores the complex communication of whales. Here’s how she’s deciphering marine-mammal communication in the field and from landlocked Denver.

What do whales say when they “talk” to each other?

That’s the mystery behind “Fathom,” a documentary coming June 25 on Apple TV+. Directed by Drew Xanthopolous, the film premiered Wednesday at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival in New York. It follows researchers Ellen Garland, Ph.D., and Michelle Fournet, Ph.D., as they observe communication patterns and vocalizations of humpback whales in Scotland and off the Pacific coast.

Also featured in “Fathom” is Leanna Matthews, Ph.D., a Biology faculty member at Metropolitan State University of Denver who joined the group as they were conducting field work in a remote location off the southeastern coast of Alaska in August 2019.

“The question we ask in the film is, ‘This sound the species makes – what does it mean?’” she said. “It’s hard to answer when you can’t ask them directly.”

There are a variety of vocalizations for different occasions among whales, including foraging, reproduction and maybe even just “talking.”

“Fathom” specifically focuses on a type of “‘whup’ call, which sounds like a reverse water droplet,” Matthews said. The film follows a playback experimental design, collecting above-water and underwater data. For a month and a half, the researchers drove around the remote location in a small boat, found whales, played a sound and observed how the animals responded.

In addition to investigating the communication strategies of humpback whales, it’s also a look into the ups and downs of the research process and an explanation of how a marine-mammal expert such as Matthews can dive into a successful research career in a landlocked location such as Colorado.

“As a researcher, I’ve been used to remote work for a long time,” Matthews said. “The great thing about field work is that you don’t have to live where the systems you study are. And there are tons of internship opportunities for students to get out there for a few months and see if it’s the right fit for them – as long as they don’t mind work that’s long, sweaty and full of bugs.”

The research by Matthews and Fournet that’s featured in the film is done through the Sound Science Research Collective, a nonprofit they founded with their colleagues that focused on using acoustic research to answer conservation questions. In addition to understanding the specific calls explored in “Fathom,” researchers had an unprecedented opportunity last year.

Though the Covid-19 pandemic ravaged much of society above ground, the contrast in the ocean was just as striking. And as Matthews’ research interest focuses on how noise from humans impacts the communications of marine mammals, it was a natural question to explore as freight and cruise ships and their normally cacophonous roar sat silent in port.

“Shipping is the lifeblood of our economy. … We use the ocean a lot, and we’re really loud,” she said. “2020 was the quietest year of animals’ lives. We wanted to know, ‘Do they communicate differently in the absence of human noise?’”

Results are still preliminary but point to a wider diversity of whale-call type in the quiet sea; a noisier environment typically produces a single specific call that occurs more often than others, Matthews said.

These communication trends are not that different for humans, she noted. Think about the challenge in trying to effectively focus on talking in loud spaces such as concerts, crowded bars or open-office environments. And whether above or below the water’s surface, it’s a valuable reminder of the critical interplay for understanding between individuals and ecosystems.

Matthews views the question of how animals communicate as itself a conservation effort and hopes “Fathom” viewers take away an appreciation of how culture exists outside of humanity.

“These intricate communication systems have existed for millions of years, and we’re just starting to scratch the surface of our understanding of them,” she said. “Diving into that is messy, complicated and important.”