Students produce a rapid, less-invasive test for HPV

Long hours and persistence pay off with a landmark and potentially life-saving screening method for a virus linked to several cancers.

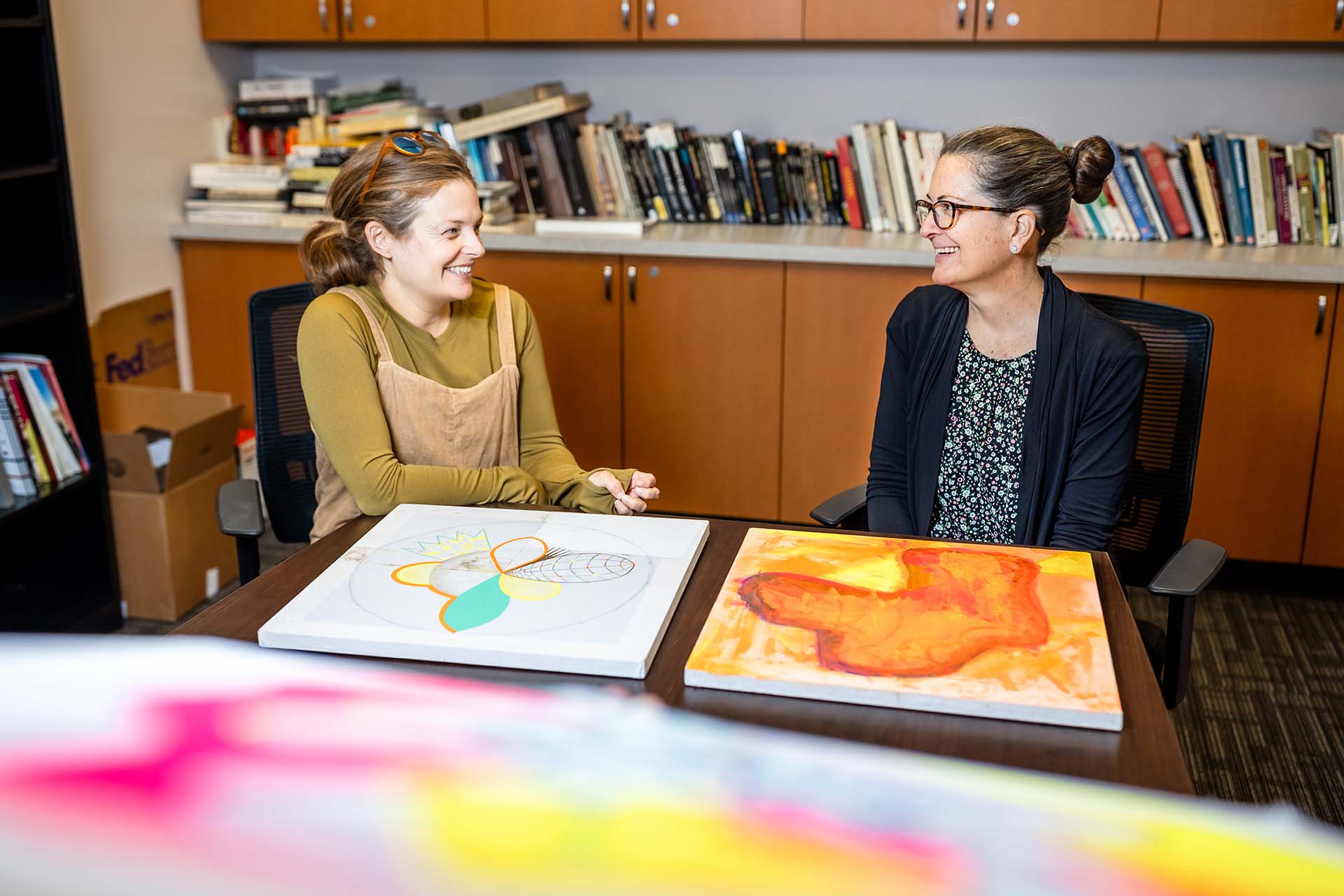

Zoe Ward has known pretty much since she started winning first place in elementary school science fairs that she wanted to be a researcher someday.

What the Metropolitan State University of Denver Biochemistry major probably didn’t know then was that she would achieve her first scientific breakthrough — and possibly her first published, peer-reviewed research — before graduating from college.

Ward, Chemistry Professor Andrew J. Bonham, Ph.D., and fellow student Gage Leach have developed a quicker, less-invasive test to screen for a type of HPV virus linked to cancer.

The test will be a finger stick to draw drops of blood for analysis, Bonham said. Results would be instantaneous — and early detection could possibly prevent cancers, including cervical cancer, that result from HPV infection.

“We could take a sample of blood and say, ‘OK, this indicates you may have HPV and need further testing,” Bonham said. More than confirming the presence of HPV, the test, which has not yet been approved for widespread use, detects a protein linked to cancer.

After a year of long hours in the lab several days a week, Leach and Ward, who graduate this month, are completing a paper on their findings and expect to submit it to peer-reviewed journals. That’s the first step toward wide use of the test.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that roughly 13 million Americans, including teens, become infected with HPV each year. More than 13,000 women in the U.S. are diagnosed with cervical cancer each year, and about 4,320 die of the disease, according to the American Cancer Society.

Although a vaccine introduced in 2006 can prevent HPV from leading to cancer, many older people who acquired the virus decades ago are still at risk, along with those who are not vaccinated before becoming sexually active.

There are more than 30 strains of HPV linked to sexually transmitted disease, and most do not cause serious illness. Only one or two strains have been linked to cancer — because they can cause changes in cells that, over years, can lead to cancer.

RELATED: Biochemistry undergrads discover new way to detect celiac disease

Currently, the majority of those virus strains are detected through Pap smears. And as Ward learned first-hand, working nights processing test samples at a lab, getting the results can take days.

“The turnaround time was three days, or was supposed to be. But a lot of times we didn’t meet that,” she said.

Even more troubling, Ward said, “Not everybody gets a Pap smear sent off to be tested for HPV. It depends on what insurance pays for. So, I thought, ‘Let’s make it more routine and more rapid.’”

Researchers had already identified proteins released by the HPV virus that are linked to cancer. The MSU Denver research team’s goal was to “design a piece of DNA that would bind to the protein,” Bonham said.

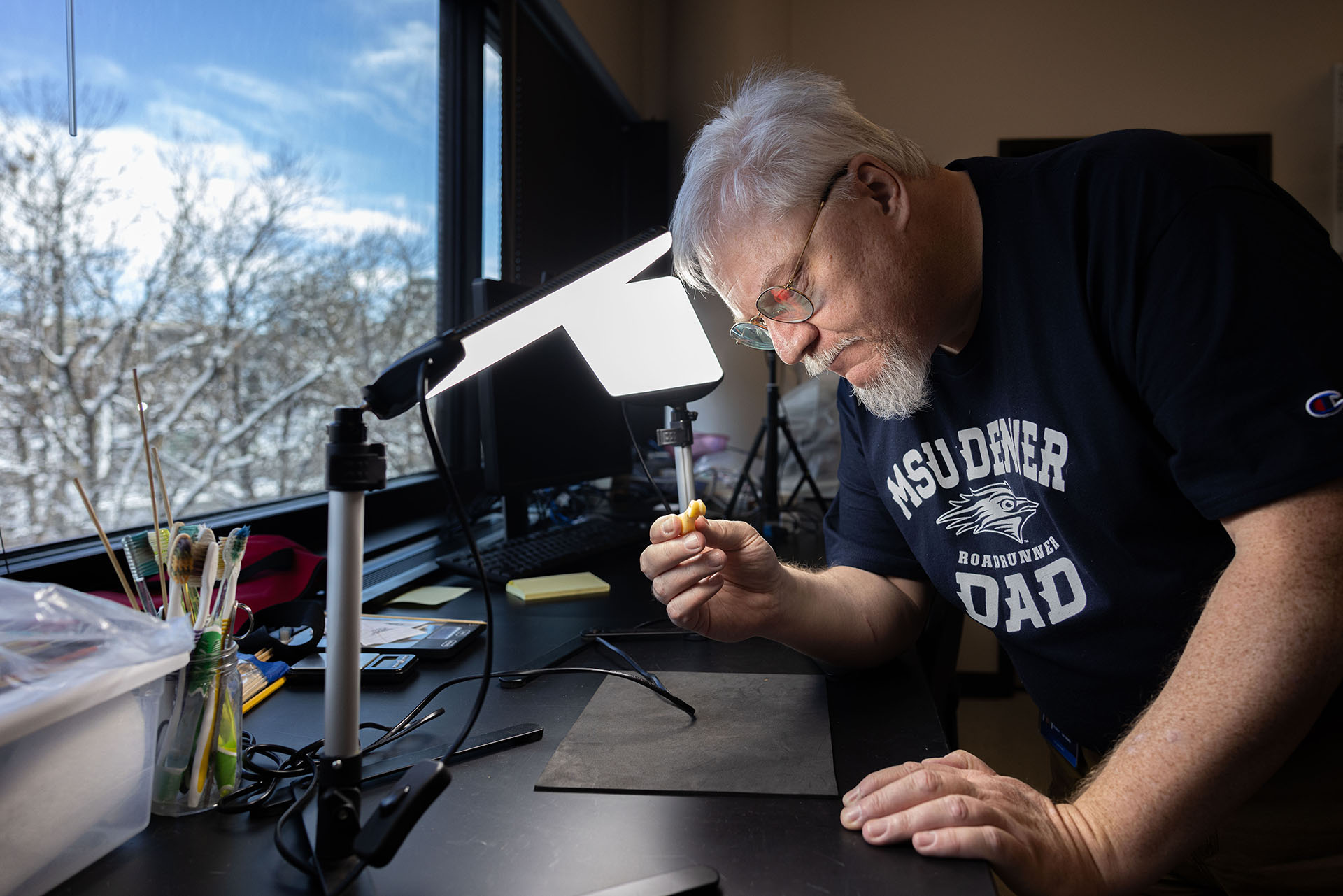

Bonham’s lab is one of a few dozen worldwide working with new technology called electrochemical aptamer-based (E-AB) sensors. Aptamers are strands of DNA, and the technology is based on changes in electrical signals when DNA and aptamers bind together.

But first, the team wanted to create the protein – a step not necessary, but one Ward wanted to do. It’s sort of the science equivalent of wanting to bake and decorate a showstopper cake from scratch rather than using a cake mix.

“We were going to purify the protein ourselves,” Ward said.

But the protein growth didn’t work out. “We were running out of time in February, so we just ordered the protein,” Ward said. “I know that cells and protein cells are really tricky, but I was honestly disappointed when we had to order the protein.”

She was disappointed and discouraged but never frustrated enough to give up, Ward said.

But the ordered protein saved the day. With it, Ward and Leach were able to produce the results they hoped for: verifying that the E-AB sensor they built detected tiny amounts of HPV.

She expects to be in the lab, tweaking the blood test and finishing the research paper until around July. After that, she said, she plans to earn a Ph.D. and work to find treatments and cures for diseases, including cancer.

In the meantime, she’s understandably proud of her work, she said. “Honestly, this could save a lot of people,” she said.

Learn more about Chemistry and Biochemistry degrees at MSU Denver.