Student with autism brings new understanding to Anthropology

Guy Davis has turned setbacks into opportunity and paved the way for a more inclusive culture.

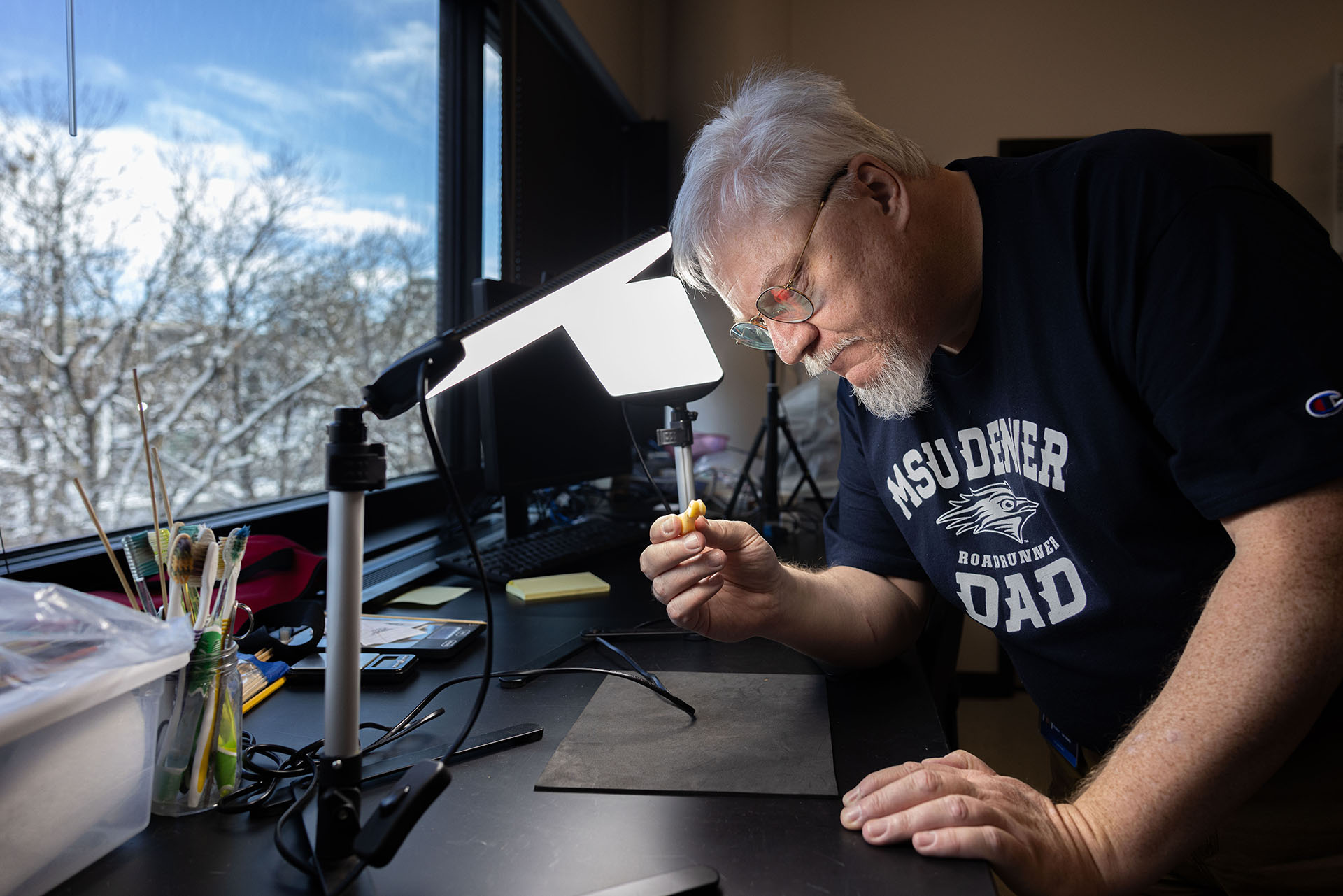

When Guy Davis walks across the stage at the Commencement ceremony in December, he’ll be celebrating a hard-earned degree in Anthropology and a winding journey filled with setbacks, resilience and rediscovery.

At Metropolitan State University of Denver, Davis found his passion for helping the neurodivergent community, particularly people on the autism spectrum, better understand and communicate with society, and vice versa. Davis, who is autistic and a parent to a daughter who has autism, said his lived experience drives his desire to improve support systems for neurodivergent individuals.

“My hope is that I can figure out a way to teach autistic kids how to join society in a way that doesn’t require them to be traumatized,” he said.

Davis first earned a bachelor’s degree from Westwood College. When the institution became embroiled in lawsuits over accreditation issues, his degree was left unrecognized — limiting his career and graduate school opportunities. He tried returning to college at CU Boulder, but the university denied his admission because of a low GPA and refused to accept his previous credits.

Still, Davis refused to give up. Years later, Metropolitan State University of Denver accepted 90 credits from Westwood, allowing him to continue his education. What began as a second chance soon became a source of belonging.

“I came here thinking MSU Denver was just like a community college,” he said. “But it turned out to be the best decision I could have made.”

Within the Department of Anthropology, Davis has become an integral member of the community — working at the department’s front desk, assisting with research projects, and co-leading the Archaeology, Language, Physical and Cultural Anthropology (ALPACA) club.

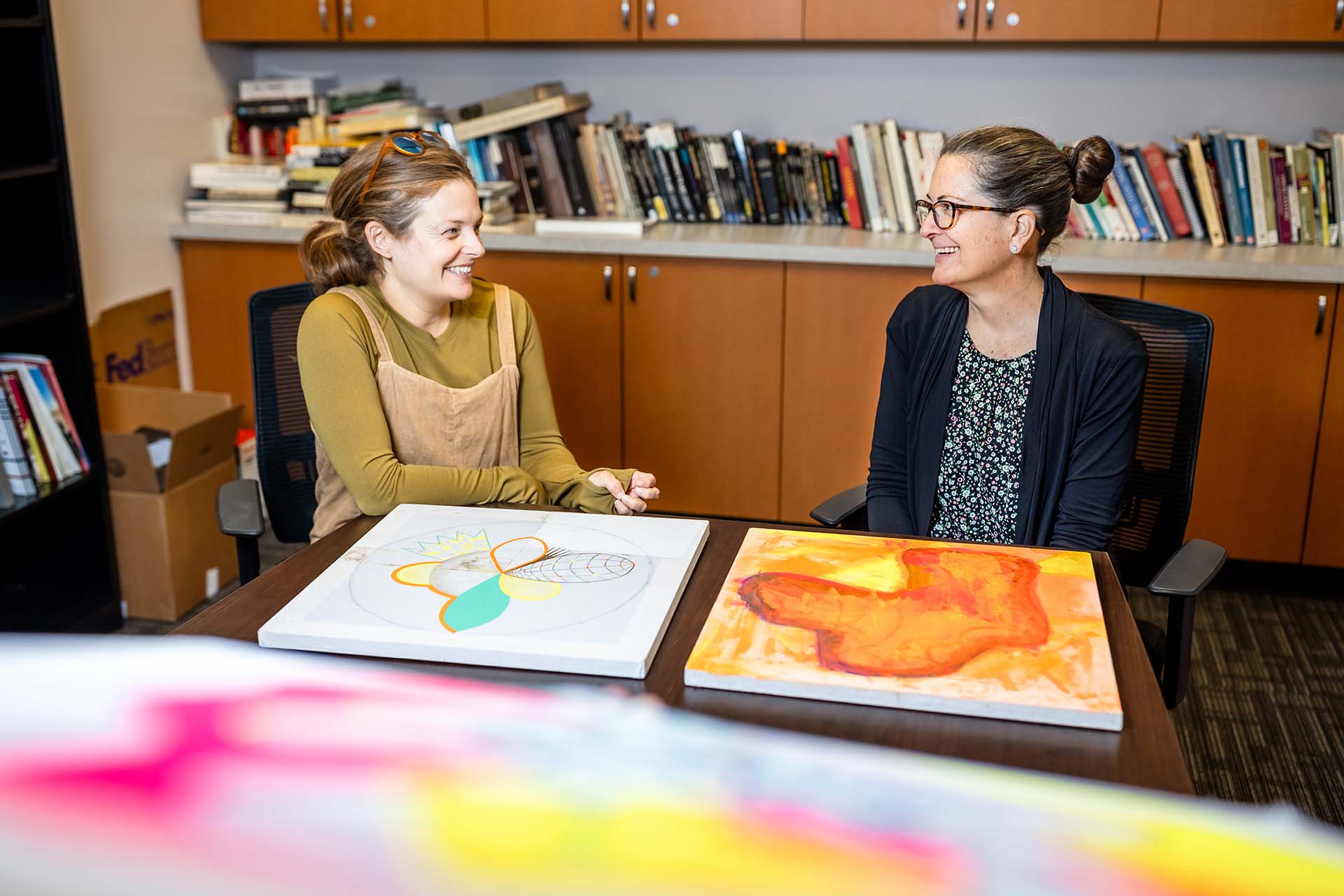

Rebecca Forgash, Anthropology professor, worked with Davis on a field project at Camp Amache in Southeastern Colorado, documenting the site where Japanese Americans were interned during World War She and fellow professor Joseph Feldman both describe Davis as deeply curious, empathetic and collaborative.

“He embodies what’s great about teaching at MSU Denver — students whose life experiences enrich everyone’s learning,” Feldman said. “I’ve had the pleasure of having him in at least one of my classes every semester.”

Both professors agree that Davis’s background as a teacher, along with his empathy and intellectual curiosity, positions him well for a future in research and mentorship. In addition, Davis’s approach to understanding autism and education from a cultural perspective rather than a medical one echoes a growing shift among educators.

“He’s really bringing a fresh look to a problem that scholars have long explained through culture alone,” said Forgash. “Guy sees other factors that might be at work.”

RELATED: VIDEO: Her autistic son needed help, so she became an expert

As a child, Davis learned to mask traits such as limited eye contact and direct communication to blend in socially. His goal now is to help the next generation meet society halfway, supporting autistic children in navigating social expectations without losing their authentic selves.

He also hopes to expand this work overseas, beginning in Japan, where he once taught English. “I’m very interested in hikikomori — people who are starting to retreat from culture,” he said. “I think there’s a connection between autism and that, because autism is a social disorder.”

Davis also argues that neurodiversity is a strength and has plans to study how cultural perceptions of difference shape support for neurodivergent individuals.

“We don’t have to fix something that’s broken. The student isn’t the problem — the system is,” said Charlie Buckley, associate professor in MSU Denver’s School of Education.

Buckley believes inclusion should go beyond accommodation or tolerance, emphasizing that differences should be elevated as assets. She advocates shifting from a traditional medical model of disability — focused on “fixing” deficits — to a social model that challenges environments and teaching methods to adapt to learners’ needs.

Davis plans to pursue graduate school abroad, most likely in Japan, where he hopes to work with neurodivergent students and continue researching hikikomori and inclusion. Eventually, he wants to bring those lessons home, implementing what he calls a “meet halfway” approach in U.S. classrooms.

“I usually liken it to this: We’re Apple OS and the rest of the world is Windows OS,” Davis said. “There’s nothing better or worse — we just think differently.”

Learn more about Anthropology and Sociology degrees at MSU Denver.