In Anne Yoncha’s class, students make dirty pictures

No, not that kind. Art and Music students turn soil data into artistic expression.

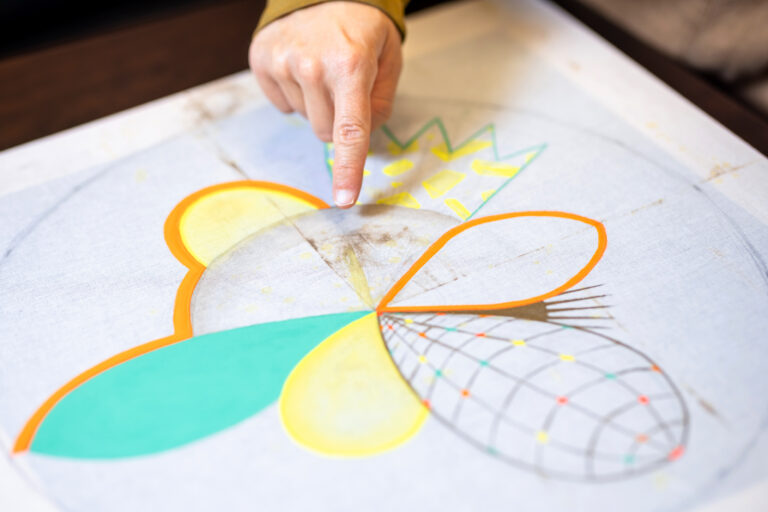

Last fall, Yoncha, a Metropolitan State University of Denver associate professor of Art, presented 17 advanced painting students with canvases that were seasoned with literal dirt. And, “dirt seasoning” — a visual representation of microbes active at the carcass site.

The canvases had spent 49 days buried in Genessee Park five, 10 or 15 meters from a bison carcass. The goal, said Sarah Schliemann, Ph.D., assistant professor of Environmental Science, was to “see what happens to the soil” as the deceased bovine decomposed.

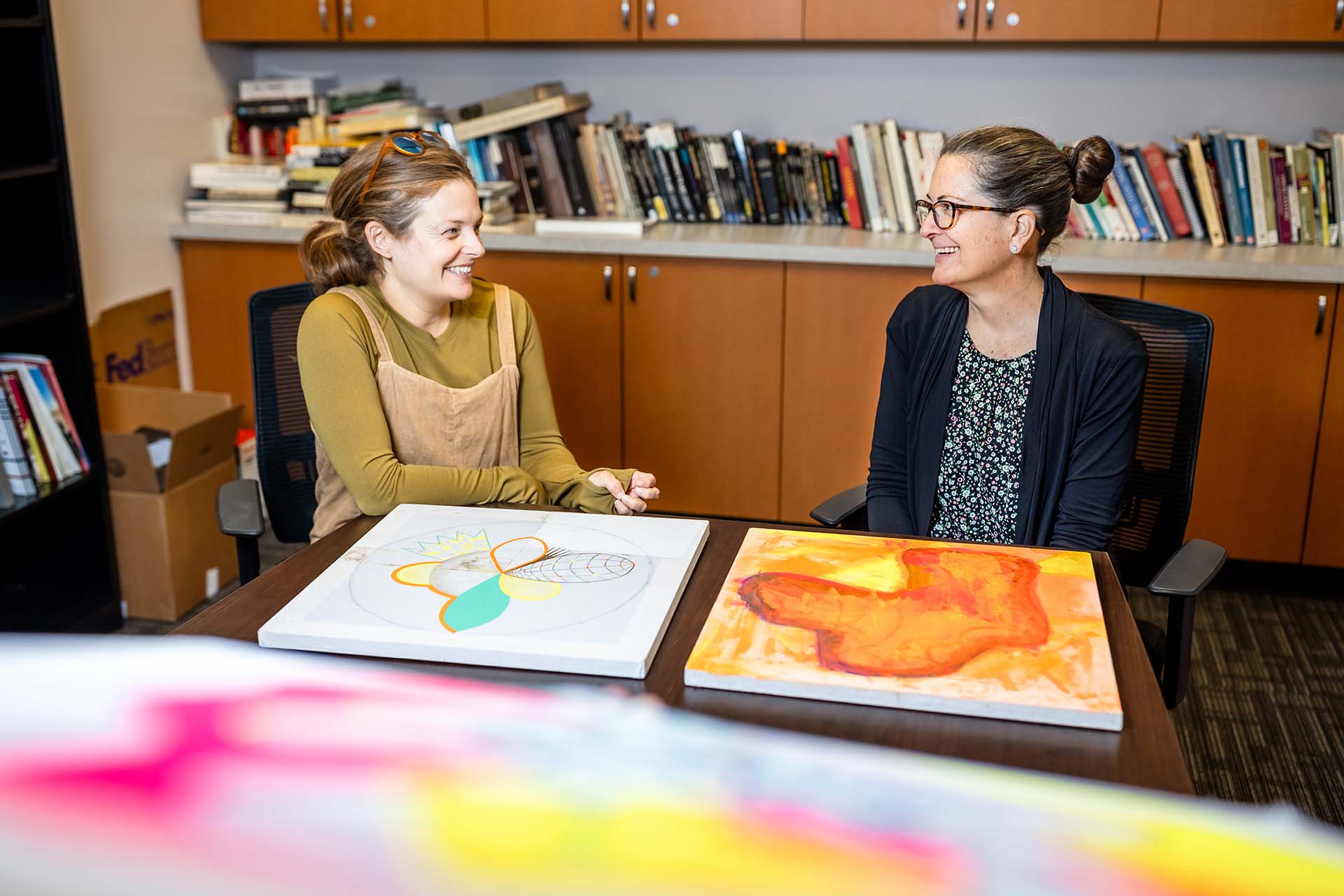

Studying soil, and how animals and environment affect it — and vice versa — is what Schliemann does. Art is what Yoncha does.

Their project united science and art.

While Yoncha handed out the dirty canvasses to students, Schliemann was analyzing soil samples from the area where the canvasses had been buried to learn the concentrations of elements such as potassium, sodium, magnesium. She wanted to document how proximity to the decaying animal affected the presence of those elements. Not surprisingly, the soil closest to the animal’s remains contained the greatest amounts of the nutrients. It’s all part of Schliemann’s work on a greater effort to understand not only how the environment impacts bison, but also how bison impact the environment.

Once the data was plotted, Schliemann turned it over to Yoncha, whose students filled the canvasses with their interpretations of that data and of the elements.

“This one’s boron I think,” Yoncha said, looking at one of the abstract works her students had produced.

“The art project lets us explore data in a very sensory way,” Yoncha said. It’s a chance to explore “How do we encode visually what these chemicals do?”

Now, Yoncha is creating an animation from the art, which will be accompanied by music.

RELATED: Dreams come true for students in the environmental sciences

Meanwhile, over in the Music Department, students also had the opportunity to transform Schliemann’s dirt into art — in this case, music.

“The idea is when we change data into different formats, we get a better understanding of that data,” said David Farrell, DM, associate professor of Music.

“The music class is working with the same soil data,” Schliemann said. “I gave them my data, which is basically a table of numbers that reflect the chemical makeup of the soil.”

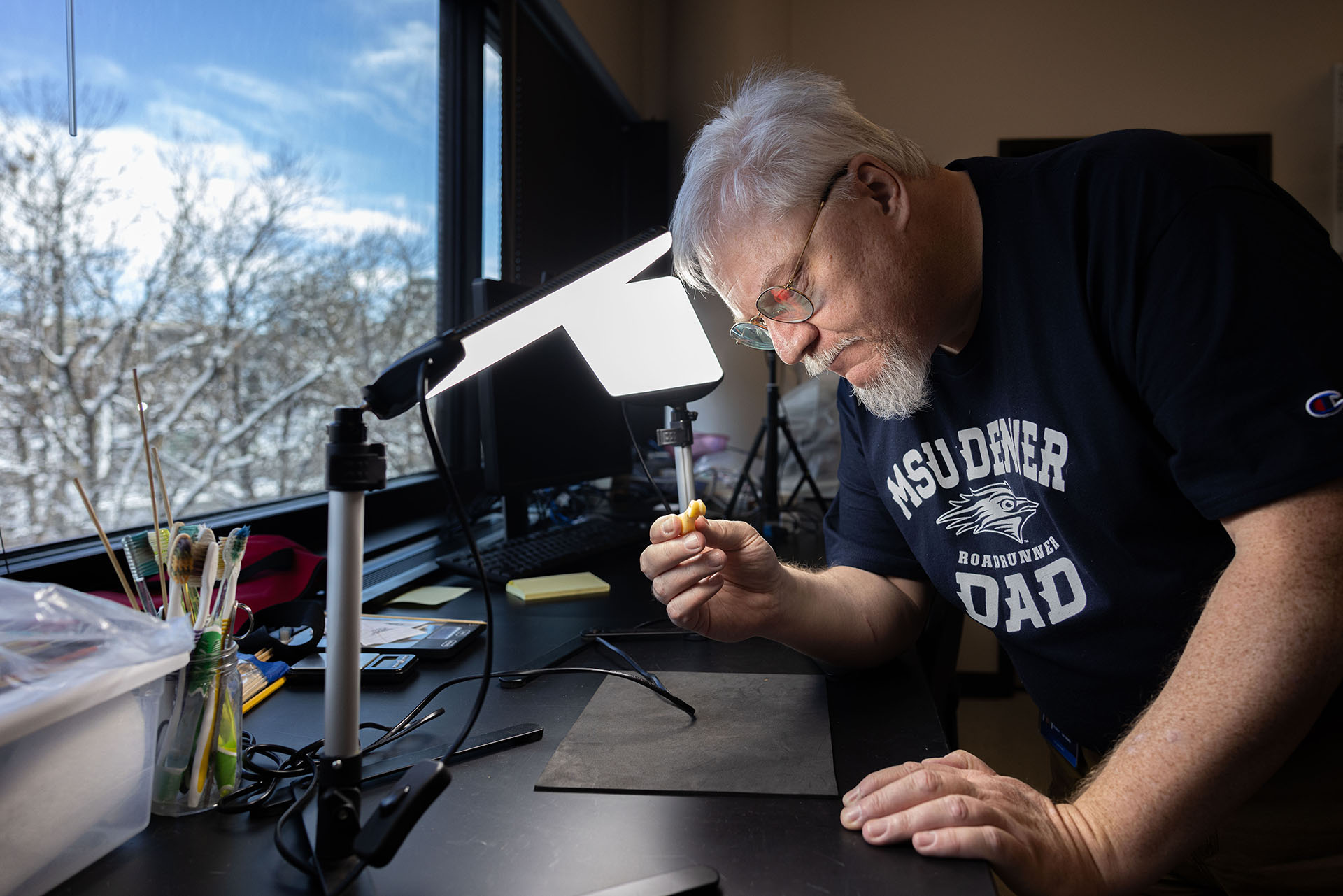

Turning that kind of data into music, or sound, is an emerging field called sonification of data, and it’s one, Farrell said, that “fits a lot of the things I’m interested in,” including computerized music and numbers.

In the first few weeks of class, students familiarized themselves with the sonification of data field, and then with the tools they needed to convert data points to music.

The three faculty members hope to share the art and musical creations with the public through collaboration with the chamber music group The Playground Ensemble. Ultimately, they’d like to showcase both at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science.

Beyond simply being a novel approach to artistic expression, Farrell sees plenty of workplace potential in sonification of data. “A lot of careers involve processing and interpreting numbers,” Farrell said. “If you’re a data person who wants people to understand your data, whether in business or education, or whatever else, this is a tool we can use to share or process our data and make it understandable.”

Learn more about Environmental Science, Music and Fine Art at MSU Denver.