Engineering students get real skills, virtually

A private donation provides cutting-edge technology to prepare students for modern manufacturing and design jobs.

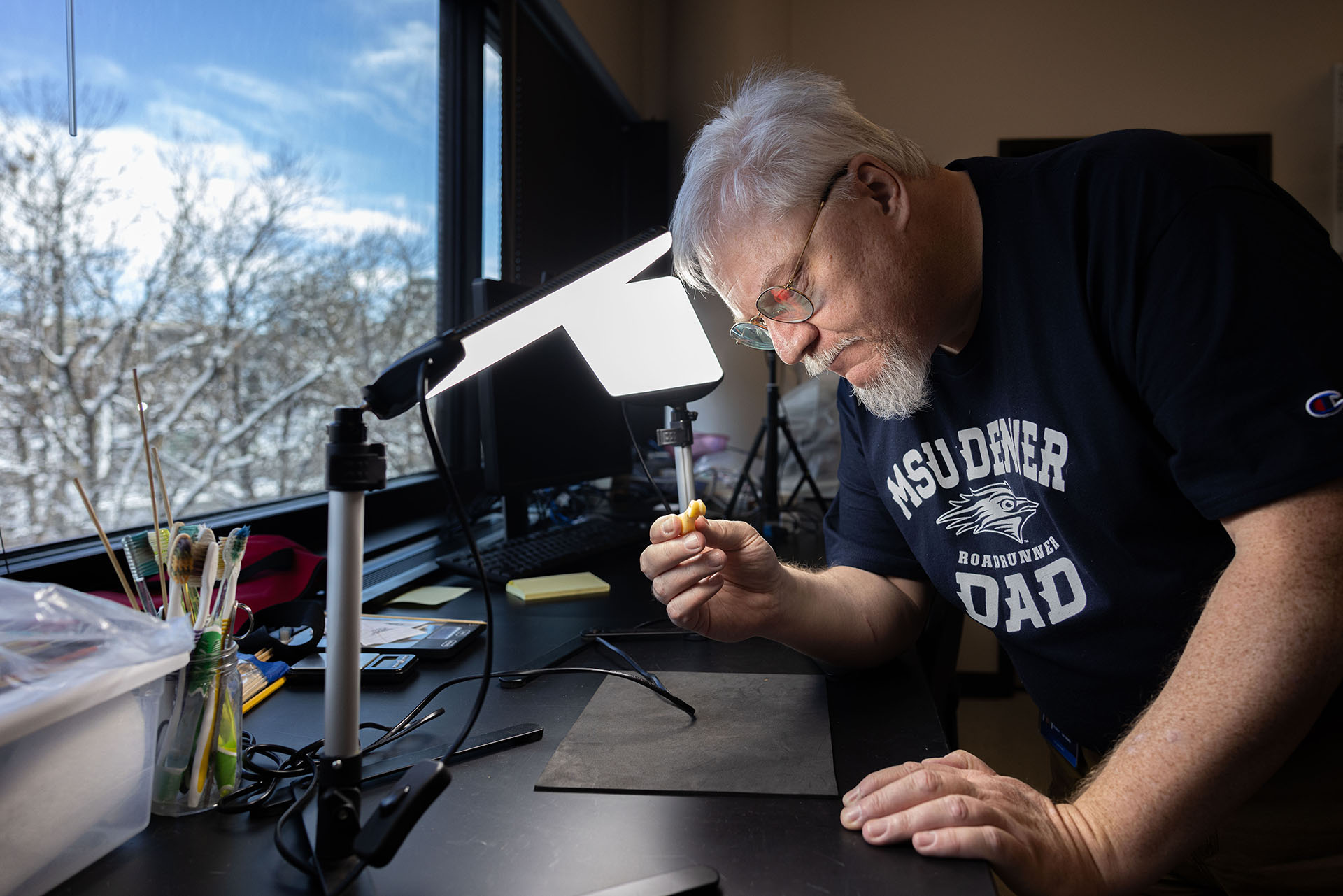

Faisal Kaweesa stands in a Metropolitan State University of Denver Mechanical Engineering Technology classroom, a pair of goggles obscuring his face and an electronic device strapped to his head, his arms stretched in front of him. He brings fingers and thumb together, moves his arms up and down, side to side, then parts his fingers. Then brings them together again to grasp at … nothing.

A small crowd of classmates has gathered around to watch, which isn’t surprising. Because from their vantage point, the whole thing looks kind of weird.

But from where Kaweesa stands, there’s plenty going on. He isn’t grasping at nothing but is using his thumb and forefinger to manipulate and measure, expand and contract a real — to his eyes — rectangle on a blueprint, which overlays the actual environment.

“I love this!” Kaweesa said.

Welcome to mechanical engineering, 21st-century style.

Thanks to a gift from the Cordova Family Foundation, the Advanced Manufacturing Sciences Institute now has 15 virtual-reality (VR) headsets, which will help more than 300 students in nine different courses build advanced manufacturing skills through immersive learning.

The department didn’t just rush out and grab the first AR/VR systems that came along.

In fact, for his senior project, Hugo Delgado, now an MSU Denver alumnus, devoted more than 200 hours to testing and evaluating 132 simulations to find the best fit for the Advanced Manufacturing Sciences students.

“What we said is, ‘We want just the top tier — the best,’” said AMSI Director Mark Yoss.

RELATED: Welcome to the fourth industrial revolution

That allows students to complete a variety of tasks and get immediate feedback. “You put on the headset, and it’s walking you through what it would be like to be in the real world doing the job with whatever the technology is that’s being addressed,” Yoss said.

The task students learn “can be as simple as ‘How do you read a scale for measuring?’ or as complicated as Ohm’s Law and how that applies in the workplace,” he said, referring to the discovery that an electrical current flowing through a conductor corresponds to its voltage.

There will be no shortage of workplaces for students to apply those skills in, Yoss said. The fourth industrial revolution — in which emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, robotics and virtual reality are the new coal, steel and giant thrumming factories — is creating thousands of new jobs. The National Association of Manufacturers predicts that by 2033, the United States will need 3.8 million manufacturing jobs and that nearly 2 million of those will go unfilled.

One key to filling that employment gap, Yoss said, is “changing the mindset that manufacturing is dirty, dull, dumb and dangerous.”

Indeed, nobody was getting dirty as they tried out the new technology in the late-afternoon Manufacturing Engineering class. The skills students were learning had little connection with the kind of manufacturing that involves heavy, loud machinery.

A few feet away from where Kaweesa pinched the air, a dozen or so students sat at tables, white goggle-shaped apparatuses strapped to their heads. The students held what looked like gaming wands, with large rings on the ends. They moved the wands around slowly, often pausing, hands in midair.

Through their goggles, the students saw disembodied virtual black gloves floating in front of them, which they used to grasp virtual measuring devices, guided by a virtual guy in a hard hat.

Eventually, a virtual notepad popped up, and invited students to write down their measurements. A correct answer elicited a voice that informed them, “Congratulations, you just got a silver medal!”

The students were learning to measure engineers’ drawings, an essential skill for manufacturing, said Jason Butler, lab coordinator for the class.

For students who have grown up vanquishing virtual foes or collecting imaginary coins by jumping around in the Mushroom Kingdom, learning by working with tools and equipment that aren’t actually there comes naturally.

It did for Mechanical Engineering student Noah Hodges, who has played virtual-reality video games but said trying to calculate exact measurements was something new. He said the headsets were helpful in showing him techniques for precise measurements, something that “is harder to do in person.”

Another advantage, Hodges said, is that “virtual reality gives you the answer right away.”

The first-year student said he hopes to put his mechanical-engineering skills to work building things like engines and motors, for which precise measurements are essential.

But there are myriad other uses for the skills learned on this kind of virtual device, said Butler. “There’s a lot of potential here, with simulations for aerospace, auto manufacturing, for medical care.”

And one other important benefit: The virtual-reality goggles keep students engaged.

“It’s pretty cool,” Hodges said. “This is probably one of my favorite classes.”

Learn more about the Advanced Manufacturing Sciences Institute at MSU Denver.