EnChroma glasses help people who are colorblind see through new eyes

MSU Denver is the first Colorado university to offer the technology to Art students and museumgoers.

Jason Burke thinks his wife’s eyes are light brown, although she maintains they are green. He has no way of knowing for sure, because as someone with red-green colorblindness, he can see shades of blue and yellow but red and green are indistinguishable from brown.

He’s amused when friends argue over what to call a color they’re looking at. “I tell them, ‘How do you think I feel when you’re arguing over it and you’re not colorblind?’”

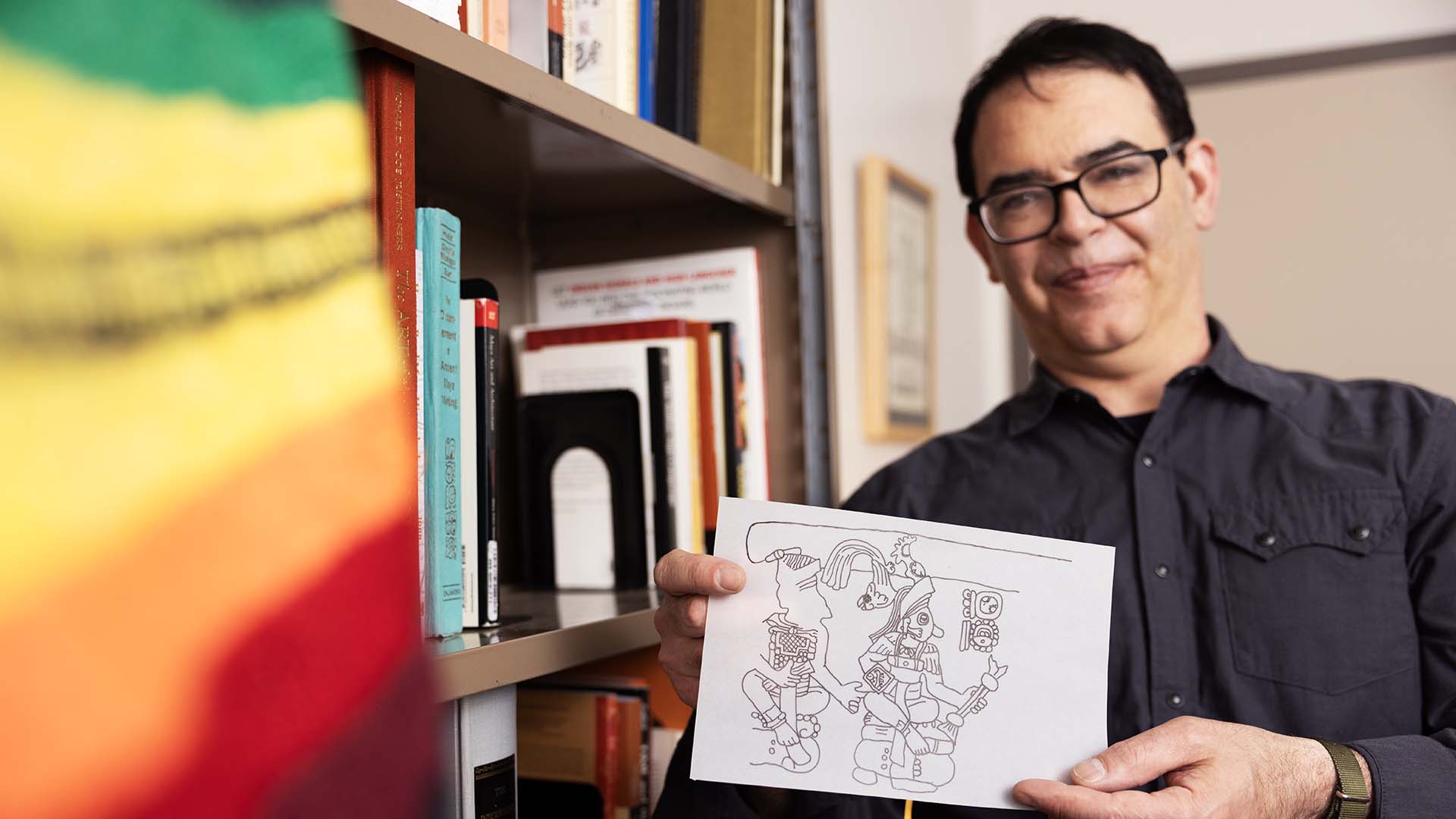

Burke, an adjunct faculty member in the Department of Mathematics and Statistics at Metropolitan State University of Denver, on Thursday will for the first time try on a pair of special glasses that filter wavelengths of light to help people with colorblindness see a broader range of colors.

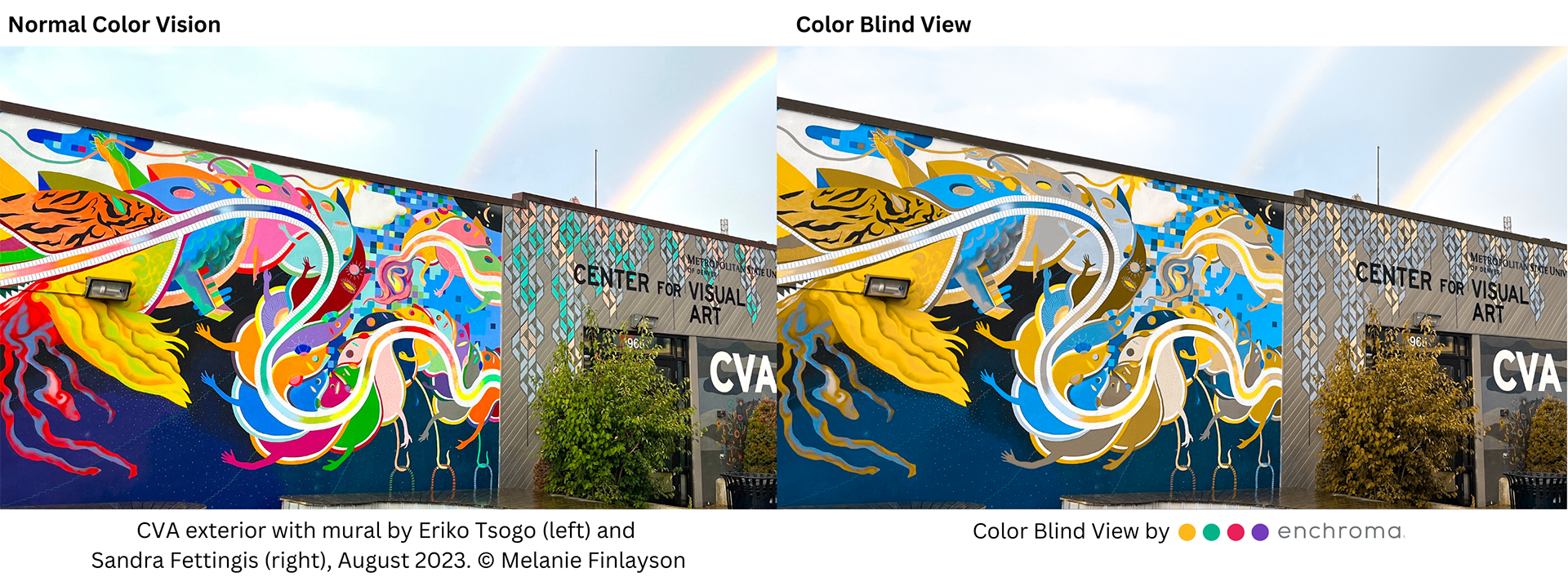

The launch event at the University’s Center for Visual Art will introduce MSU Denver students and faculty members to EnChroma colorblind glasses. The gallery will loan the glasses to visitors, while the University’s Art Department plans to make them available for students and faculty members. MSU Denver is the first university in Colorado to acquire the glasses through EnChroma’s community-partnership program.

Jill Mollenhauer, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Art Department, spearheaded the initiative after learning that Denver’s Museum of Contemporary Art offered EnChroma glasses for visitors to wear while touring its galleries.

“I was interested in part because I have two brothers who are colorblind,” she said. “I thought, ‘What a great idea.’ I teach Art History, and color is such a major visual element. If you’re red-green colorblind, you’re going to have trouble navigating, especially in Art History classes.”

Mollenhauer learned that the California-based company partners with art galleries, museums and universities to make the glasses available through its community-partnership program. She contacted the CVA’s director and curator, Cecily Cullen, to suggest that the gallery acquire some glasses as well.

Under the program, the CVA and the Department of Art each purchased two pairs of glasses and a kit, and then EnChroma donated two pairs of glasses. “It’s very affordable for us,” she said.

The glasses, which have violet-tinted lenses, look like sunglasses. “They don’t magically cure colorblindness, but they will allow the vast majority of people who suffer from colorblindness, especially from red-green colorblindness, to see a greater variety of colors, as well as additional saturation and detail,” Mollenhauer said.

The CVA’s mission is to serve as a resource for the Auraria Campus but also for the greater population, Cullen said. “We’ve worked really hard to make art accessible through everything we do,” she said. “When Jill brought this opportunity to us at CVA, I thought, ‘What a great opportunity for us to think about how people experience art.’”

RELATED PHOTOS: The art of the installation

After trying on the glasses, Cullen said they make colors more vibrant, even for those with typical vision. “It is kind of like putting on rose-colored glasses,” she said.

The kit includes two pairs of glasses, one of which is for kids, and two oversize glasses that fit over regular prescription glasses.

“It’s an exciting opportunity for people who are colorblind to see in a different way,” said Cullen, whose father was colorblind.

Kent Streeb, EnChroma’s vice president for communications and partnerships, said part of the company’s mission is educating the public about the challenges faced by people with colorblindness.

“We’re trying to elevate awareness about the prevalence and the effects of colorblindness, (such as) daily challenges, the aesthetics of life, enjoying nature and being able to appreciate art more fully,” he said. Those living with the condition may have trouble matching their clothes, judging when meat is done cooking or picking out ripe fruit in the grocery store.

“Playing board games is always a nightmare too,” he said. “It’s just another thing that they have to think about all the time.”

Colorblind students often struggle in the classroom, yet only 11 states in the U.S. require testing for colorblindness, he said. Students often can’t interpret maps, graphs or PowerPoint presentations, because they are unable to distinguish color-coded graphics. “We found almost half of people don’t find out until after seventh grade that they’re colorblind, and 20% not until after high school or college,” he said.

In red-green colorblindness, which accounts for about 98% of those who are colorblind, cone cells in the retina that register red and green wavelengths of light overlap, so the brain doesn’t receive the signals needed to correctly register the colors, Streeb said. EnChroma’s glasses incorporate special optical filters that selectively remove wavelengths of light where the overlap is greatest.

The condition is inherited via a mutation on the X chromosome, affecting about one in every 12 men and one in every 200 women — about 13 million people in the U.S. and 350 million worldwide, he said. Well-known figures who are affected include musicians Sting and Neil Young, former President Bill Clinton, actor Nicolas Cage and Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg, Streeb said. “It’s always surprising,” he said. “We learn new people every day who are colorblind.”

Jason Burke, the MSU Denver faculty member, discovered he had red-green colorblindness as a child when he found he was perceiving colors differently from his friends and family. “I remember being at school and painting weird colors,” he said. “When I see a rainbow, I just see blue and yellow.”

Over time, he has learned to infer colors by perceiving subtle differences, based on what others have told him. Looking at a tree, “Why are the leaves green and the rest of the tree is supposed to be brown?” he said. “You start to associate dark things with brown, light things with green. I’m not thinking about the color; I’m just thinking about whether it’s darker or lighter.”

In a way, Burke says, his colorblindness is a superpower because it has taught him to be highly attuned to nuances in the environment.

When he was younger, he was watching a billiards game on TV with his family when the color suddenly became distorted, he said. His relatives couldn’t follow the balls on the table, but he had learned to distinguish them in the absence of color. “I could tell them apart because I’m used to trying to adapt,” he said. “I just adapted to what I had to do.”