Bugging out: What to expect during this year’s rare double swarm of cicadas

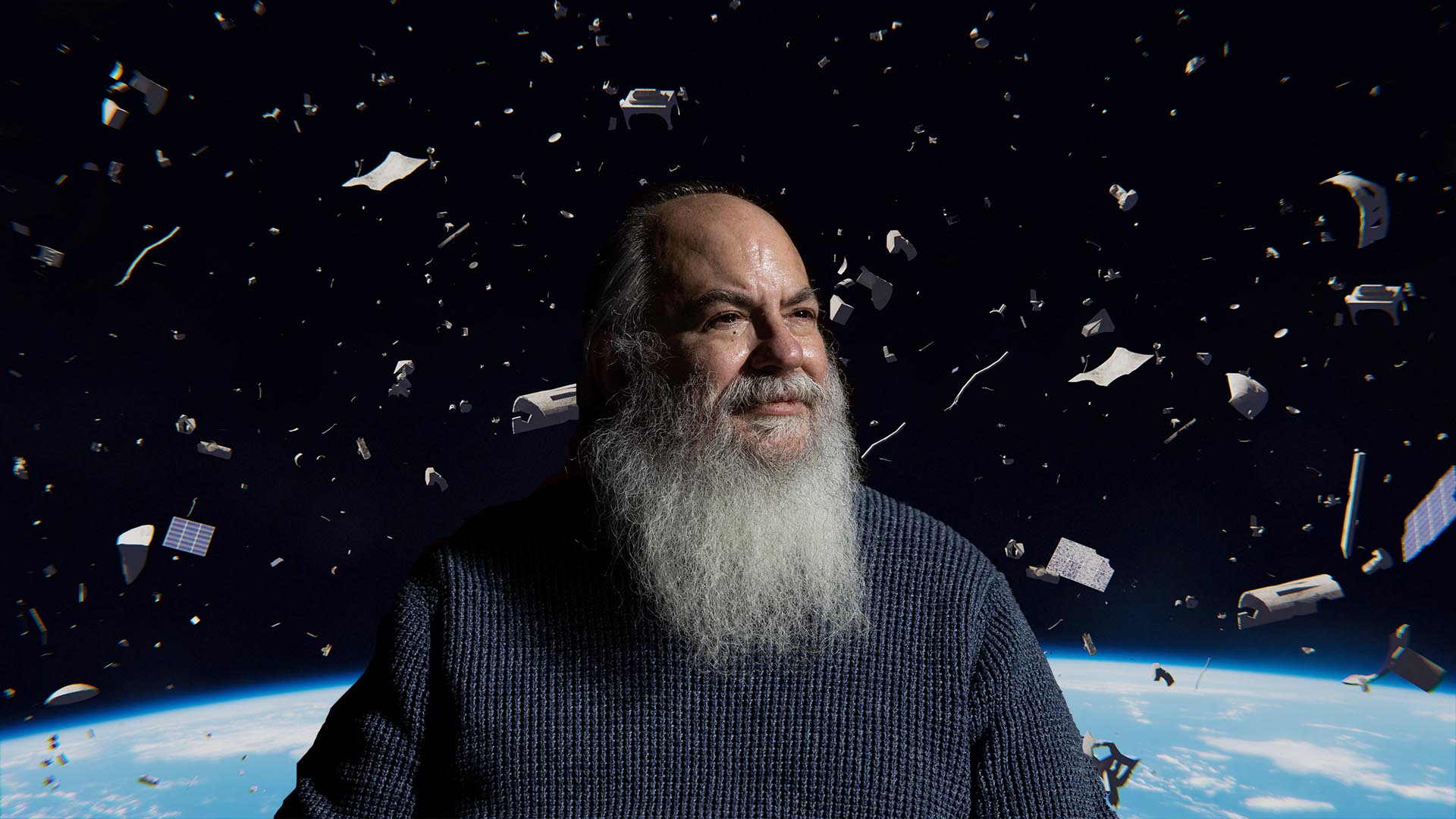

MSU Denver entomologist Bob Hancock says the infestation will spare Colorado. Here’s where to go to see it.

If you’ve been following the news lately, you’ve probably heard about a rare double swarm of cicadas that will surface this spring. Two groups of the big-eyed, winged insects will simultaneously emerge by the billions from underground, mate and live out their brief lives.

One place that won’t happen is Colorado, says entomologist Robert Hancock, Ph.D., a professor in Metropolitan State University of Denver’s Department of Biology. The Centennial State does have endemic cicada species but not the ones known as periodical cicadas, which spend a decade or more living in the soil as nymphs feeding on plant roots.

“In Colorado, we don’t have any of these periodical cicadas,” he said. “That’s particularly relevant because a lot of people have been asking, ‘Are we going to see the event?’”

One of the broods of periodical cicadas that is emerging this season, known as XIX, spends 13 years underground, Hancock said, while brood XIII lives for 17 years in the immature state. It’s the first time since 1803 that the two broods have co-emerged, and there’s one place where their respective ranges will overlap, making it an attractive destination for cicada tourism.

“If you were one who wanted to follow the swarms and notch your belt, you could set your target on central Illinois,” he said. “There’s one county in particular that may really be a hot spot where you can see both of these broods.”

Hancock said it will be an unforgettable spectacle.

“If you go to someplace like DeWitt County, you’re going to find a couple of woodland park areas,” he said. “They’re going to be coming out of the soil. They’re going to be flying around, and they are in the canopy — that’s where you find them. They’re flying all over the place when they’re in these masses.”

RELATED: Why mosquito season came early this year

The sheer number of insects in these swarms is staggering, he said, citing a study conducted in Illinois in the 1950s that estimated 1.5 million cicadas per acre.

Although cicadas pose no harm to humans, being amid a swarm of insects belonging to the periodical-cicada genus Magicicada can be triggering for people with insect phobias, Hancock said.

“They’re dark and evil-looking,” he said. “They have orange markings, and they’re generally black otherwise. Their eyes are pretty funky — they look like aliens — and they also make a heck of a racket because they’re singing for sex, basically. They really are identifying a potential mate by sound.”

He witnessed a cicada swarm in Cincinnati in the 1980s while he was a graduate student. “I just remember coming to an intersection and there were just these insects flying crisscross every which way,” he said. “They were running into the car. There were lots of crushed cicadas on the sidewalks and the road.”

He later guessed he had encountered thousands of cicadas, a tiny fraction of the total. “That was pretty good, but on the volume dial that was probably somewhere between one and two,” he said. “If you’re really lucky, you can get to a place where it’s just overwhelming. But if you’re there for that purpose, it’s kind of cool.”

Hancock said several of his students are planning on traveling to Illinois for the swarm, which is expected to start in mid-May and run through early June.

“I don’t know if I’m going to go to get into it,” he said, “but if I do, I know where I’m going.”