The science behind sci-fi

How do you untangle fact from fiction on the big screen? Our movie expert explains in a new book.

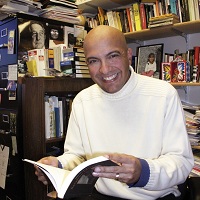

When Vincent Piturro, an English and Film professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver, first launched the summertime Science Fiction Film Series in the Mile High City, his idea was ingeniously simple: Team up with local experts to explore the intersection where scientific fact meets cinematic fiction.

Meet the Author

Sept. 25: Torpedo Coffee Sept. 30: Denver Museum of Nature & Science Oct. 7: The Cube Students from the MSU Denver FiLM Club will be on hand at all three events to collect nonperishables for the Roadrunner Food Pantry. All author proceeds from the book will be donated to the Food Bank of the Rockies. |

|

Now, he has turned more than a decade’s worth of popular events into a book: The Science of Sci-Fi Cinema. RED interviewed Piturro to learn more about the book and how movies that captivate our imagination stack up against real-world science.

Why did you want to write this book?

Our events at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science have been super-popular for over a decade now, so we decided to make a permanent record of our favorite collaborations.

Each chapter features both an artistic and scientific analysis of a particular movie, and there’s really nothing else like it out there. Putting the book together was a challenge (herding scientists can be like herding cats) but great fun, and we’re all pleased with the result.

Having consulted numerous scientific experts, do you now find sci-fi movies more or less plausible?

Actually, I never found these movies plausible to begin with. Once you start looking at them through a scientific lens, guided by real-life scientists, it’s surprising how badly off the mark most movies are.

Interestingly, the most scientifically accurate film in this collection is one of the oldest: “2001: A Space Odyssey.” It’s always fascinating to hear scientists talk about this movie. So many of director Stanley Kubrick’s details – concerning space travel and survival, and right down to the instructions for the zero-gravity bathroom – were spot-on.

What was the most hilariously off-target piece of sci-fi hokum?

This might surprise readers because the movie seems pretty convincing, but the biggest load of bunk we found came with the solving of the aliens’ language in “Arrival.” My MSU Denver Linguistics colleague Andrew Pantos rips the whole concept to shreds in our book, and it’s a fascinating read.

The big problem is that Amy Adams’ character uses sound waves – and sound waves alone – to figure things out. But in reality, linguists always have to connect sounds to some kind of intellectual process (such as laughter, anger or certain actions) to decipher any meaning. Otherwise, it’s literally just noise. From a scientific viewpoint, Adams is simply watching a group of giant squids honk at her through a thick plate of glass.

Your book covers “Jurassic Park,” and now scientists are apparently trying to bring back woolly mammoths. Coincidence much?

My paleontologist colleagues and I have often talked about the question of reviving extinct species while presenting “Jurassic Park” at the events, and I have to tell you: It’s a hard “no” from all of them.

In the movie, scientists extract dinosaur blood from a prehistoric mosquito preserved in amber, then use the DNA to create live dinosaurs. But here’s the issue with that: Amber is basically a terrible medium for preserving DNA, so it just wouldn’t survive. It’d be like placing a yogurt in a refrigerator and expecting to find a tasty snack 500 years later.

The chapter on “Contact” explains that the science was dead wrong, but the filmmakers needed to cut corners to make the story work. Ultimately, how important is it for a film to appear real and true?

It’s not important at all, because film is first and foremost an entertainment medium. So your movie absolutely should be engaging, well-structured and well-executed, but it doesn’t need to be accurate.

If you want to gain some genuine scientific knowledge, go read a book. (In fact, go read my book!) Most scientists I know actually find sci-fi movies pretty ridiculous and laughable.

Do sci-fi movies ever get it right?

Yes, they do sometimes kind of stumble into accuracy. I’m thinking particularly of “The Day After Tomorrow,” the slightly overblown Jake Gyllenhaal blockbuster from 2004, which aimed to portray a nightmarish future hit by ecological disaster.

The thing is, some of the scenes depicted in that movie – raging wildfires, extreme flooding – are actually happening right now. It always creates an interesting dynamic when movies hit the target like that.

Which sci-fi movie are you still waiting to see get made?

This is a complete no-brainer for me. William Gibson’s classic cyberpunk novel “Neuromancer” is totally cinematic and would translate beautifully to the big screen. Published in 1984, the book was not only brilliant for its time; it has also been hugely influential.

Gibson invented (or reappropriated) a lot of the language of sci-fi (“cyberspace,” “matrix,” “meat puppet”) that we still use now. I don’t doubt that in the right hands, the book could make a great movie or TV series.

Which juicy futuristic themes are still out there, just waiting to be explored on the big screen?

I don’t know if there are so many new themes left. But I’d certainly like to see more environmental sci-fi movies – particularly ones that explore the human aspect of ecological disaster rather than just the usual CGI-heavy, New York-got-flooded-again blockbusters.

The finest quality of one of my book’s selected movies – a little-known gem called “The Perfect Sense” – is that it addresses an all-consuming global crisis (everyone gradually loses their five senses) without ever betraying its tight focus on the story of its two main characters.

Should we be worried that your selected movies exploring darker, dystopian themes – such as “Children of Men,” “Upstream Color” and “Perfect Sense” – somehow seem more realistic?

We probably should have been worried a long time ago. Most sci-fi movies are set in a distant future that’s so removed from our own experience, it creates a nice safety buffer. We can happily watch shiny spaceships blast each other to pieces all day.

But I’m a big fan of “near sci-fi” – where it’s not too far in the future; you do recognize those situations; you could imagine those bad things happening to you. Near-sci-fi movies that address ecological themes are often so powerful because the distance between their fictional worlds and what we see on the news is constantly shrinking.

Many sci-fi movies explore the first, halting communications between humans and aliens. Do you think you will live to see this actually happen?

I don’t think we’ll advance to that point during my stretch on Earth, but maybe we will during my son’s lifetime. Personally, I’m pretty sure there are aliens out there. But if they’re looking down at us, they probably think we’re a bad bet and are assuming we’ll be gone in a couple of hundred years or so. Sadly, I don’t think the Vulcans are eager to meet us anytime soon.