Special educators

Amid a shortage of special-needs teachers, three educators completed an Alternative Licensure Program to fill the need and find their passion.

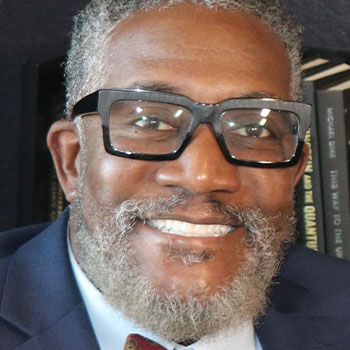

After eight years of drawing up football plays and scheduling practices, Bruce Jones is now drawing up individualized education programs and scheduling class rotations for 10 special-education grade-schoolers who filter in and out of his class during the day.

The former high school football coach was always drawn to special education, having grown up with a close friend who had a brother with special needs. So Jones drew up a plan to change his career path.

“I’ve always had a heart for those students that are struggling learners,” Jones said. “I’ve always had a heart for other people and wanting to serve. It just kind of fit.”

Jones is doing exactly what he was meant to do and exactly what Colorado – and the rest of the country – needs.

Education Week reported that the number of special-education teachers in the United States dropped 17% between 2006 and 2016, while the number of special-education students remained steady. Because of the teacher shortage, the student-teacher ratio in special education increased from about 14:1 to 17:1 in the span of a decade.

Since the rate for all students and teachers stayed close to 16:1 during the same period, the student-teacher ratio is now higher for special education – where students benefit most from one-on-one instruction.

“Special education is in dire straits everywhere in the country, and this is an economic problem – people with special needs rely on the state if they can’t gain skills,” said Elizabeth Hinde, dean of the School of Education at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

Boosting the workforce

Jones was working as a special-needs paraprofessional when his boss encouraged him to become a full-fledged teacher. So the Littleton native enrolled in MSU Denver’s Alternative Licensure Program, which aims to boost the teacher workforce by helping those with a bachelor’s degree in any area to become licensed teachers.

Last May, a decade after becoming the first person in his extended family to go to college, Jones graduated with his Master of Arts in Teaching in special education. He’s now a significant support-needs teacher at Coyote Creek Elementary in Douglas County.

Kristine Hazelett, who teaches 20 special-education students at Vassar Elementary in Aurora, also answered the call to teach through MSU Denver’s Alternative Licensure Program. She was a military spouse and stay-at-home mom whose son had learning difficulties. After reading up on his struggles and seeing how much targeted instruction helped him, she decided to become a special-education paraprofessional when she went back to work. Much like Jones, Hazelett had a mentor who persuaded her to become a teacher too. She said MSU Denver’s program was convenient but challenging.

“I’ve talked to other people who have gotten a master’s degree in teaching, and they either didn’t have to do the teacher work sample or they didn’t have to do a capstone project. So I learned a lot,” Hazelett said. “I spent my time at Aurora Hills Middle School, and even though it was extremely challenging going to school and teaching at the same time, it was invaluable.”

Changing careers

Not all those who pursue a teaching license seek out jobs in schools first like Jones and Hazelett. Patty Formosa found teaching after a 30-year career in real estate. She didn’t realize how unhappy she was with her job until she lost it. Her biggest client took its real-estate needs in-house, and when her job suddenly disappeared, she realized that she felt relieved.

At the recommendation of a friend, she began substitute teaching to bring in some money, then fell in love with it. She learned about the special-education teacher shortage when she was hired to sub in Denver Public Schools. That perception was reinforced when she applied for a job at Cole Arts and Sciences Academy in Denver, where she was asked to start the day after she interviewed.

Formosa, who expects to complete MSU Denver’s Alternative Licensure Program in May, says she was immediately drawn to special education and loves building relationships with the kids who are all too often left behind in the classroom.

“So many of these kids just get lost, and they’re capable of doing more than people think they can when they’re given the opportunity to,” she said. “The kids have their moments – they’re kids, after all – but at the end of the day, I just love every single one of them.”

Formosa has a growing caseload of 17 students between third and fifth grades. She had a different kind of moment in November during a school lockdown, a tense situation caused by police activity in the surrounding neighborhood. Formosa saw one of her students talking to a school administrator.

When she approached, the administrator relayed what the student had said.

“He was just telling me that he used to hate to come to school but now he likes coming because he gets to spend time with you,” Formosa recalled. She had to fight back tears.

“It’s all worth it when they get excited about something. You see them gaining confidence in their abilities,” Formosa said. “That tends to be the biggest problem: Their self-esteem is so low because they think they’re stupid and other kids call them stupid. The biggest battle is getting them to realize that they’re not stupid, they just learn differently.”

Do the right thing

Wanda Wilson, an instructor with MSU Denver’s Alternative Licensure Program, has a message for every student who enrolls in the program.

“Every day, there is a family and a student that are counting on you to do the right thing,” she tells them.

Bruce Jones, who gave up Friday-night lights for the everyday fight of supporting students with special needs and their families, said that was his biggest takeaway from the program.

“I take that really serious. You’ve got a family who a lot of times is grieving over this loss of the future or the questions of what’s going to happen next,” Jones said. “When you’ve got a student who’s a struggling learner because of some sort of disability or impairment that they didn’t choose – these are young kids that were born this way or had a tragic incident that happened to them – you never know what the trajectory is.

“You push them as hard as you can, and it’s so rewarding when you have success.”

His hard work has already been recognized by his community. He received a “Shining Star” award from the Douglas County School District, which required a nomination from a student’s parent or caretaker.

Jones hopes to one day take his advocacy for special education to the principal’s office, as he’s pursuing his principal’s license because not many administrators have a special-education background.

“We’re kind of running all day, but I love it,” he said. “With special education, everything’s just a little more magnified. It’s a little more emotional. The stakes are a little higher. It’s a really hard job, but the reward is very high, too.”