Researchers study sewage for COVID-19 clues

The State of Colorado, wastewater-treatment facilities and university scientists team up to collect data that can serve as an early-warning system for coronavirus outbreaks.

Front Range sewage will soon be a source of critical data in Colorado’s fight to stop the spread of COVID-19.

This month, Colorado launched a one-year, federally funded pilot program to test sewage at Front Range wastewater-treatment facilities for the virus. The study is being run by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment with Metropolitan State University of Denver and Colorado State University conducting laboratory testing of the sewage.

While symptoms of coronavirus don’t appear for five to 14 days, those infected with the virus begin shedding it in their excrement within days of infection, said Tracy Fielder, 2019 MSU Denver biology graduate serving as an associate researcher on the project. By studying sewage, Fielder and her fellow biologists can collect data that provide a clearer picture of how many COVID-19 carriers are in a community.

“The whole goal is developing a system of early warnings,” she said. “If the detected (COVID-19) signal starts to rise, we can respond by alerting officials to respond accordingly.”

The wastewater-based measurement approach is one among many for effective surveillance and detection of the virus.

“A lot of people aren’t going to the doctor to get tested both because they’re asymptomatic or can’t afford it,” Fielder said. “Without that data, it’s hard to have a good handle on how many people are infected and we struggle to track the trail of the disease throughout society.”

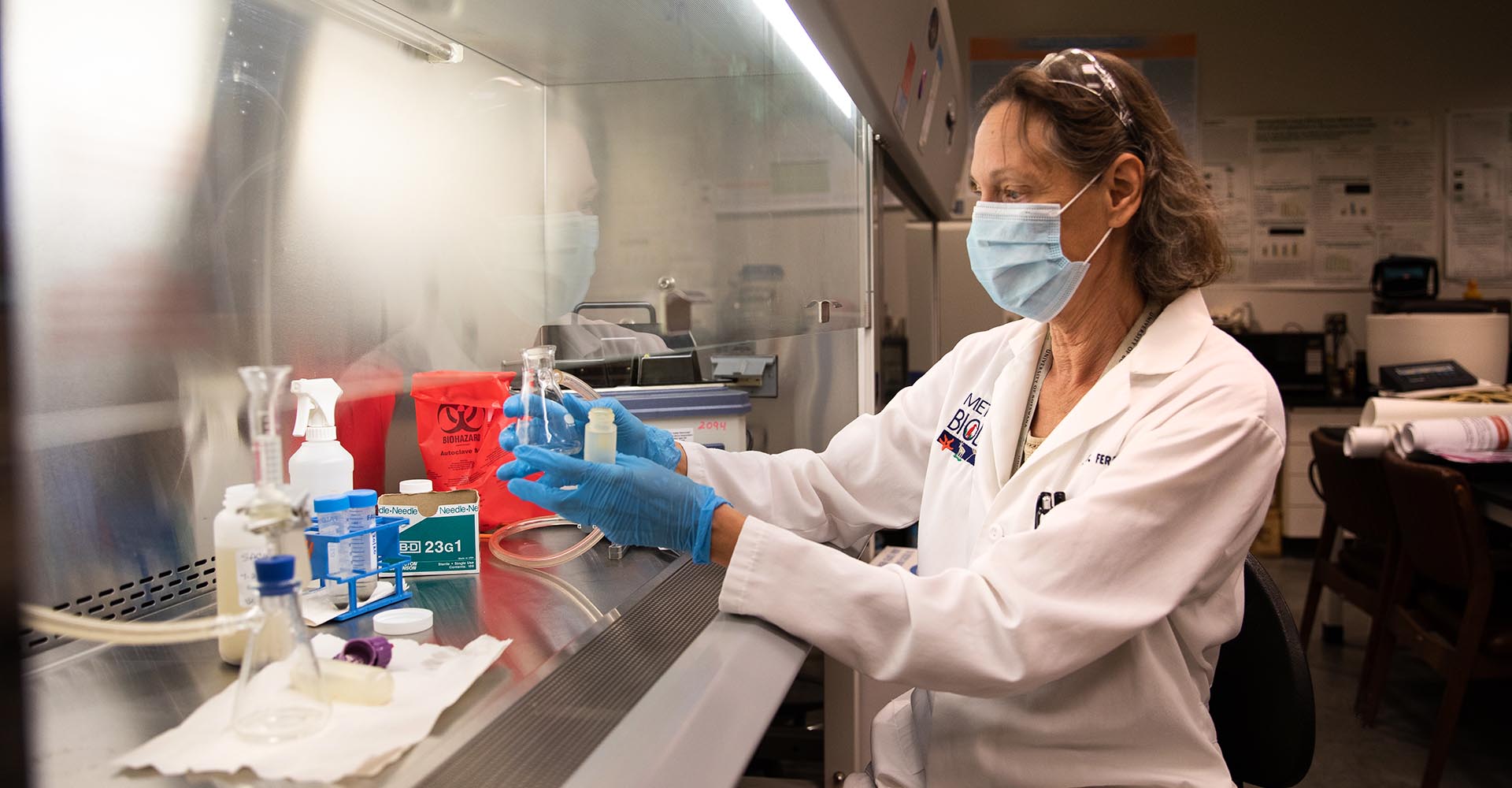

Fielder is working alongside Rebecca Ferrell, Ph.D., professor of biology at MSU Denver. Wastewater is collected in a 24-hour “snapshot” from a facility and sent to labs, including one run by Ferrell. The sample is pasteurized first to inactivate the virus, then it is filtered to separate large particulates and bacteria. Polyethylene glycol and salt are added to precipitate the process so that after a spin in a centrifuge, researchers can dump out most of the liquid while leaving a concentrated pellet of ribonucleic acid (RNA).

RNA is extracted from the pellet and converted into DNA copies, and characteristic sequences of the SARS-CoV-2 viral genome are detected using quantitative polymerase chain-reaction (Q-PCR) analysis. Results are then quantified to examine how much specific SARS-CoV-2 DNA exists versus the rest of the sample and measured against a threshold signal.

The whole process takes about two days.

If the lab finds a big spike in the virus, researchers can notify leaders, experts and hospitals such as Denver Health so they can prepare staff to respond to a potential surge, Fielder said. Conversely, a reduced or absent signal could serve as affirmation of phased-reopening policies.

“(Feces are) a canary in the coal mine,” Fielder said.

Boston-based Biobot Analytics pioneered the process that MSU Denver biologists are using initially to detect opioid usage; the company, which has ties to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, modified its technology to test for SARS-CoV-2, the strain of coronavirus responsible for COVID-19.

Recognizing the value of such wastewater testing for Colorado’s efforts to stem the spread of COVID-19, Ferrell first connected wastewater facilities with the Biobot lab in the early stages of the pandemic. However, shipping sewage samples from Denver to Boston proved to be logistically prohibitive for the scale required.

“In the spirit of collaboration, Biobot shared their protocols so other places could continue testing,” she said. “That’s when we looked at it and said, ‘Wow – we can do this in our labs at MSU Denver.”

Jim McQuarrie, director of comprehensive planning and innovation with the Metro Wastewater Reclamation District who helped coordinate 16 wastewater utilities involved in the project that represent two-thirds of the state’s population, credited the CDPHE’s leadership and Ferrell’s advocacy to advance the project as a “grassroots standup.”

“We’re all on the same side when protecting the public health and our environment,” he said. “And today, this kind of information is contributing to improving that in a 21st-century way.”

Ferrell sees the wastewater-surveillance effort as a kind of process improvement, as the data collected may also serve to improve algorithms by correlating caseloads from local health departments, providing opportunities for those studying epidemiology.

“That could involve predictive modeling with local treatment plants,” she said. “I think there’ll be a market for wastewater-based epidemiology, which we can absolutely teach our students to navigate by putting together a set of educational experiences to model.”