Drought conditions fuel record Colorado wildfires

The state’s drastic dry-out and four major fires underscore the water challenges facing the West.

The Pine Gulch fire north of Grand Junction Thursday grew to 139,006 acres, becoming the largest wildfire in Colorado history.

Three other major wildfires – the Grizzly Creek fire in Glenwood Canyon, the Cameron Peak fire north of Rocky Mountain National Park and the Williams Fork fire west of Winter Park – are also scorching tens of thousands of acres as a hot, dry August comes to a close.

Drought conditions, meanwhile, cover the entire state, with extreme and severe drought conditions blanketing more than 93% of Colorado, according to the United States Drought Monitor.

While drought fuels wildfires, their relationship is complicated and impacted by short-term weather patterns and human activity. The state’s drought conditions and fires are each symptoms of a changing climate that in combination are prolonging and intensifying fire season, presenting new challenges to the state’s water managers.

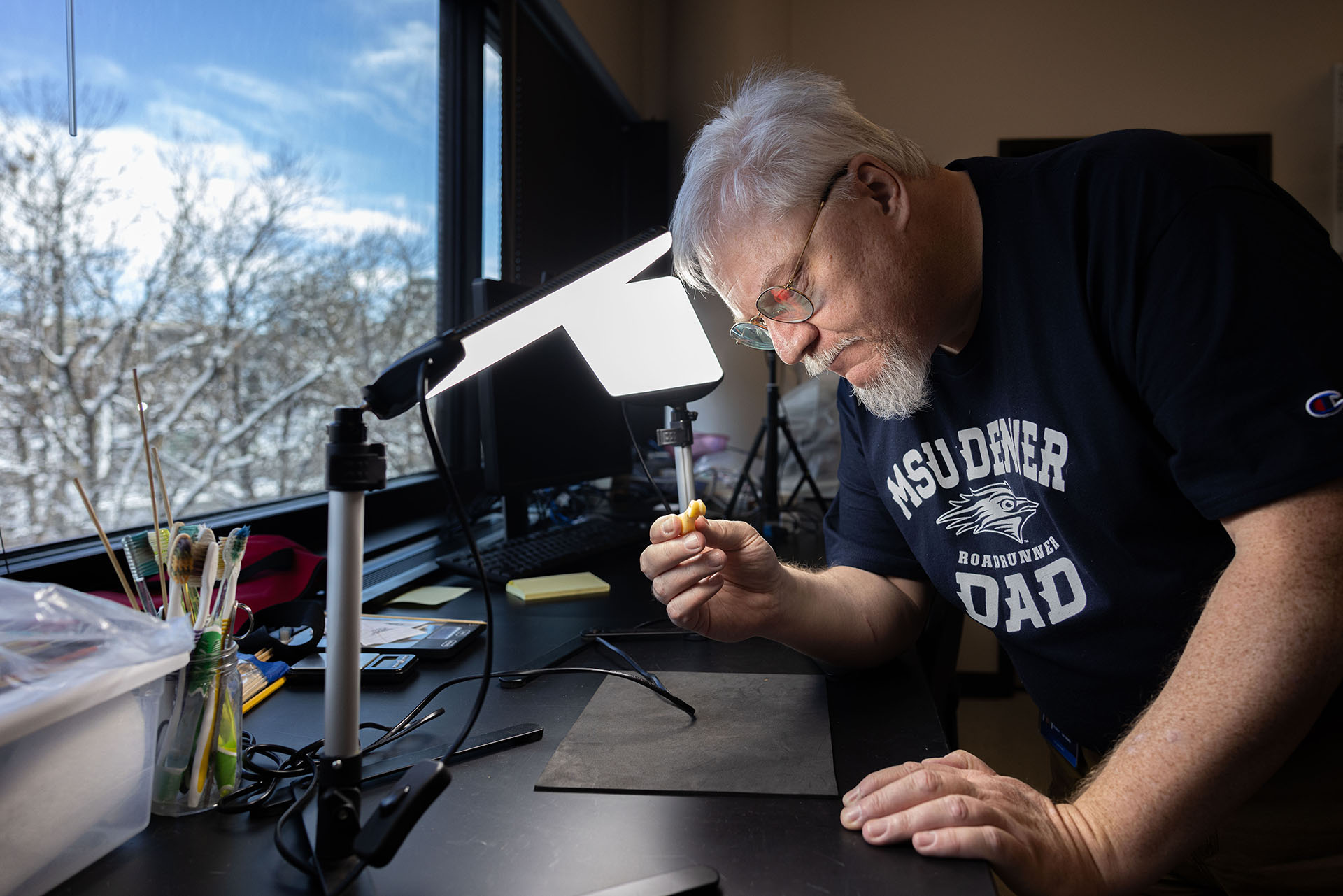

“Western communities and water managers will be dealing with the effects of these fires for years to come,” said Tom Cech, co-director of Metropolitan State University of Denver’s One World One Water Center.

In June 2019, Colorado was drought-free, but after a dry fall and average winter snowpack, Colorado’s descent into drought was precipitous, said Thomas Bellinger, Ph.D., a hydrologist who teaches environmental science and policy, snow hydrology and water law in MSU Denver’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Science.

“Last January, the existing snowpack actually led to predictions of little drought,” he said. “But a warm, dry April and May melted that snow fast, providing more time for hot summer temps to dry us out.”

Data collected by Colorado’s “snowpack telemetry” stations – known as Snotel – indicated the state’s snowpack mostly melted by mid-June, two to three weeks before the average melt dates and almost five weeks prior to the melt of the 2019 snowpack.

The high-country snowpack is Colorado’s water tower, Cech said. The melt nourishes ecosystems throughout the spring and summer and is captured by reservoirs for urban and agricultural use.

“Rising temperatures are an underlying concern for all water managers,” he said. “Just a degree of temperature change shifts the melting pattern of snowpack, and current projections are for climate change to increase temperatures by 2 or more degrees.”

But rising temperatures are just one factor affecting snowpack, Bellinger said. Melt is being sped up by increasing dust-on-snow events, wherein dust from the deserts of the Southwest – and as far away as China’s Gobi Desert – coats snow atop Colorado’s mountains. That snow then absorbs more of the sun’s rays, speeding up its melt.

Colorado’s Center for Snow and Avalanche Studies and regional water agencies launched the Colorado Dust-on-Snow program to monitor the phenomenon, counting three documented events last winter.

Demonstrating the complicated relationship among drought, wildfire and weather, however, is the reality that last year’s wet, green summer – the product of an El Niño cycle – likely provided fuel for this year’s fires, Cech said.

“All the growth from last summer dries out fast with the hot, dry and windy conditions we experienced this year,” he said.

April-July 2020 was the third-driest on record for Colorado, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Centers for Environmental Information. Moving into fall and winter, NOAA predicts a 60% chance of La Niña development in the Northern Hemisphere, which could result in fewer storm systems and a dry winter in Colorado.

Human behavior is the other wild card in the wildfire equation. Gov. Jared Polis said last week that three of the four large fires in the state – the Cameron Peak, Williams Fork and Grizzly Creek fires – were likely caused by humans.

The Pine Gulch fire was caused by a July 31 lightning strike in a remote high desert, and wildfire is a natural part of the state’s ecology, Cech said. But with risks elevated by drought and climate change, Coloradans – and visitors to our state – need to be aware that their actions can cause these devastating fires.

For instance, the Grizzly Creek fire is burning in the municipal water supply of Glenwood Springs and in the headwaters of the Colorado River watershed that supports 40 million people downriver, he said. Meanwhile, the Cameron Peak fire is burning near the headwaters of the Cache la Poudre River, one of two surface-water sources of drinking water for Fort Collins.

“Our actions in the mountains can affect whole communities,” he said, “ and not just in the burn zone.”