Redefining working class

Most college students also have a job. Here's how savvy undergrads are finding career-related work experience on campus.

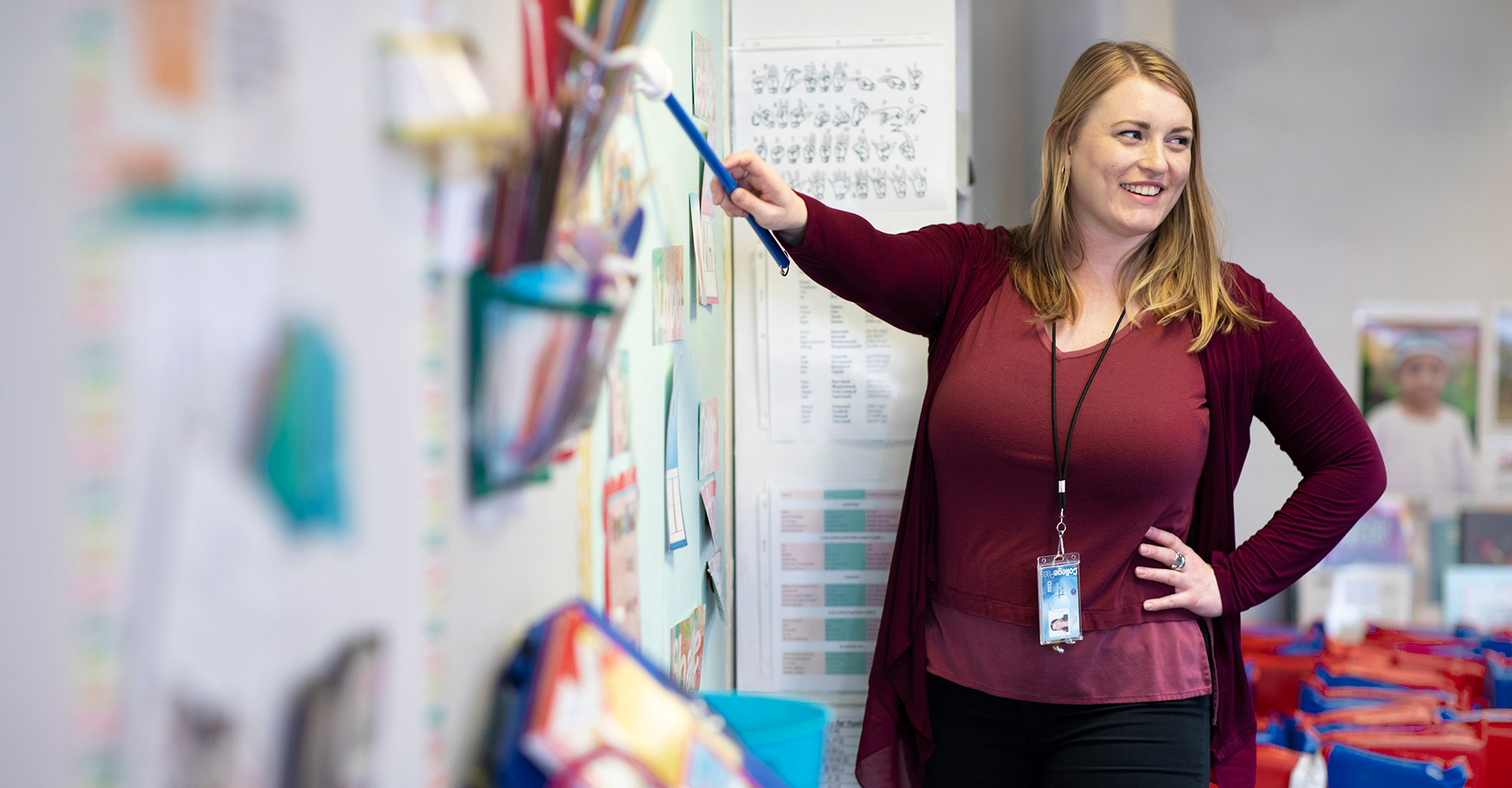

Caroline Edinger has known for a while that she wants to be a teacher.

She first realized her calling at age 14 when she scored a ski instructor gig. Since then, she has striven to find employment that advances her goal of becoming a teacher, she said.

The early childhood education major at Metropolitan State University of Denver landed a part-time job last year as an assistant teacher at the on-campus Auraria Early Learning Center.

“I’ve always thought, ‘Why waste my time doing anything else when I could be gaining experience working with kids?’” she said.

While working during college is nothing new, Edinger represents a new norm in higher education, as students are increasingly taking on jobs that pay their bills while providing valuable experience in a field related to their studies.

In fact, nearly 70% of college students are “working learners,” according to a recent report by Georgetown University’s Center on Education. At MSU Denver, the data show that closer to 80% of the student body are active in the labor market while formally enrolled at the University.

While earning income is essential for students paying tuition and bills, the estimated 14 million student-workers – 9% of the U.S. workforce – are also essential to the economy, according to the report, which also explains the transformative potential of students earning work experience.

“To be valuable and propel workers up the career ladder, work experience should relate to the student’s field of study and include reflective learning on the job,” the report said. “Reflective learning on the job … is essential because it empowers working learners to think intentionally about their future career trajectory and development, identify potentially relevant skills to develop, and develop a lifelong learning disposition.”

Diverse opportunities

Having long recognized the importance of school-work balance, MSU Denver has helped develop for its students employment opportunities in a diverse array of fields.

Mechanical engineering major Ryan Comeaux made pizzas for Dominos for a decade before landing a “learning assistant” job at the University. In the position, created by a 2016 pilot program aimed at reducing the failure rate in college algebra courses, Comeaux mentors peers and facilitates groupwork in math classes he already passed. He also earns a pedagogy class credit, a permanent indication that he has learned to educate others.

“The process of teaching is universal, Comeaux said. “It doesn’t matter whether you’re teaching someone how to make a pizza, which I did for 10 years before coming to school, or learning how to use the Pythagorean theorem to solve a basic triangle problem.”

Kyle Warren, a brewing sciences major, works full time in his field as a brewer at Tivoli Brewing Co. on campus. He started as an intern and was promoted to a full-time brewer in the span of a single semester.

“You couldn’t ask for anything better,” Warren said. “It’s full-time brewing experience, and I get to take every single one of my classes and apply the knowledge in my everyday life.”

The list goes on: Working for Met Media, the student media organization at MSU Denver, can get you paid, portfolio-building experience on your way to landing a full-time job in your field before you even graduate. Majoring in events and meeting management? Get paid to plan events for the Office of Student Activities. How about aerospace? Take a paid internship to work on York Space Systems satellites, without even leaving campus.

Students need to work, and the workforce needs workers. Getting paid to get career experience pays off for everyone. Just ask Comeaux.

“I no longer work at Domino’s, because I get to spend my time on campus teaching math instead of running to sling pizzas and then going home to do my homework,” he said. “I get to stick with math all day. That’s what I’m learning in my degree program, and that’s also where I make my money.”

Flexibility required

Edinger’s employment at AELC is an ideal match for both parties: She has taken enough classes and spent enough hours in classrooms to earn her early childhood teaching certification, while AELC hires year-round and maintains flexible scheduling for its teachers in order to maintain low teacher-student ratios.

“They understand (student schedules) because they only hire students for this position at the Auraria Early Learning Center,” she said. “There was a whole wave of us that were early childhood majors taking classes together, and we all said, ‘Why are we all working halfway across town? We should just work here.’”

Edinger works 30 hours a week on average, but sometimes puts in just one or two hours a day after class. Recently, when she needed to dedicate more time to her field placement – a graduation requirement – she was able to scale back her work hours without issue. In May, she will take six weeks off for a study abroad trip and then return to work 40-hour weeks for the rest of the summer.

“It’s super convenient,” Edinger said. “Not a lot of preschools will accept assistant teachers to work really random hours.”