“Wherever you are is sacred because you’re there”

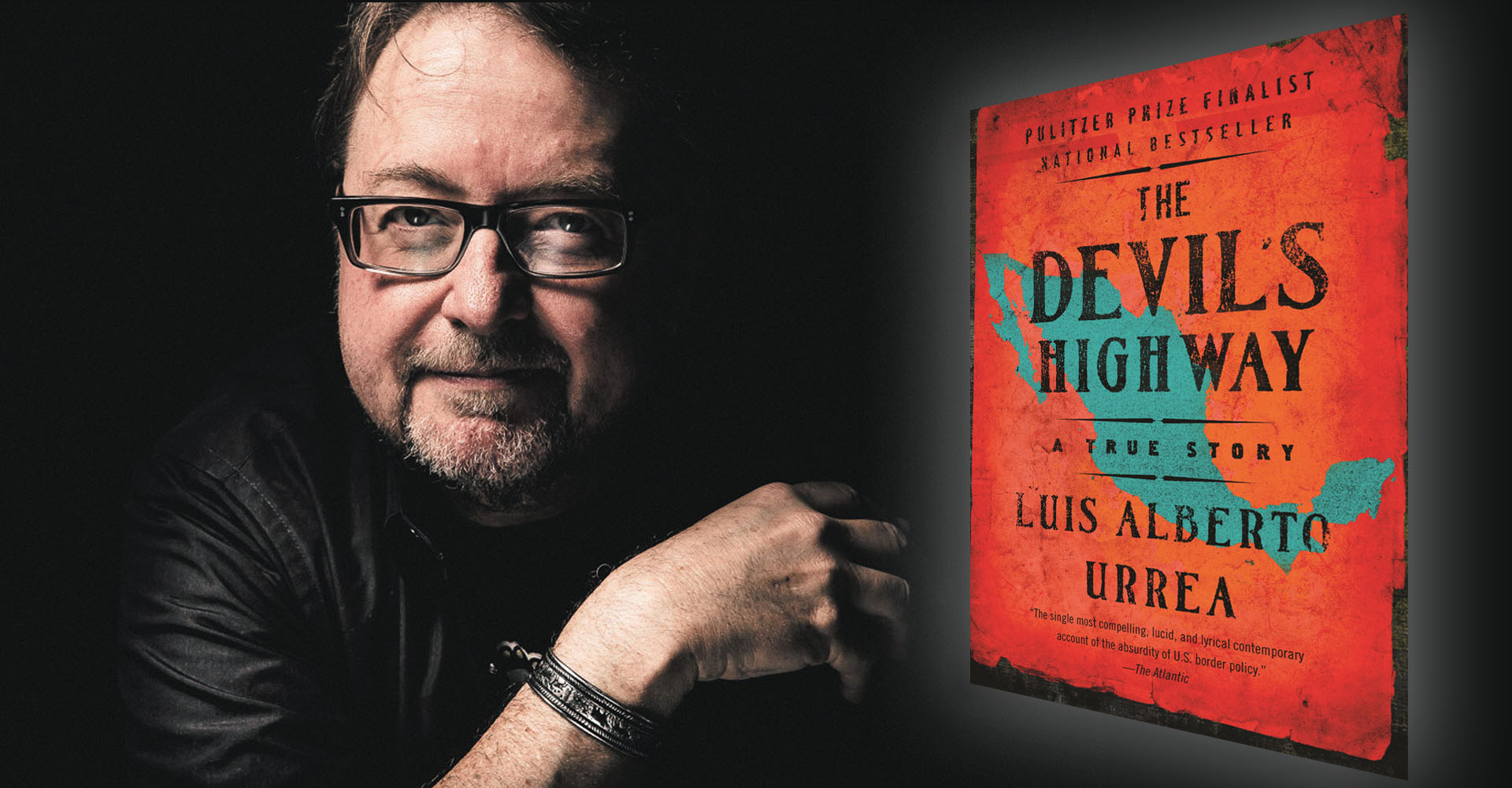

Best-selling author Luís Alberto Urrea talks immigration and storytelling in advance of his upcoming visit.

Pulitzer Prize finalist. The Big Read selection by the National Endowment for the Arts. A best book of the year from the Washington Post.

Luís Alberto Urrea’s resume reads as a litany of prestigious literary accomplishments. But what goes into the making of his success? For the Richard T. Castro Distinguished Visiting Professorship recipient, who will address the Metropolitan State University of Denver community Oct. 25, it’s a confluence of ever-shifting narratives, always authentic and fit for tumultuous times.

That includes the Independencia neighborhood of Tijuana, Mexico, Urrea’s birthplace, which now is a body-dumping hotbed for drug trafficking. And a love for musicians such as Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison and Led Zeppelin, fueling his rock-and-roll approach to storytelling and foundation as a “literary badass,” as NPR called him.

As part of Urrea’s visit, MSU Denver students will read and discuss his 2004 book “The Devil’s Highway.” The true story details the attempted crossing of an infamous stretch of the Sonoran Desert that claimed the lives of more than half of the 26 men who set out.

We caught up with Urrea to talk about the relevance of the professorship’s theme, “Love, Loss, Triumph: Todos Somos Inmigrantes (We Are All Immigrants)”; the importance and meaning of place; and advice for burgeoning writers to tell their own truths.

Where does the call to be a writer come from?

I’ve always loved to read and write. Being educated in Southern California in the 1960s and ’70s, I didn’t see any Latino/Latina authors at the time, however. The only one I was vaguely aware of was Cervantes’ “Don Quixote” – and even then, I thought it was a book about a donkey!

I wrote because I had to, though, and as a refuge from the kinetic street action that was going on around me. By the time I was in high school, I threw myself into becoming a writer; I was the guy with the notebook. And though I didn’t believe someone like me would be able or allowed to publish something, I wrote anyway.

When I got to college, that’s when the avalanche really happened – all of these poets, writers, other Chicanos doing interesting things; I was in the midst of this ocean of brilliance. All of this time, I was writing.

And all of us are writers – it’s a very ancient and ritualistic process that’s the outgrowth of sacred song and dreamtime work you find in religious texts; you’re selected by the ancestors to do this. I didn’t realize I was on such a sacred journey at the time.

Why is it easy for so many Americans to forget their own history as immigrants and products of immigrants – and the original indigenous populations who were here first?

That question’s been around for as long as I can remember. When I hear people say, “But my family immigrated here legally,” I ask them, “Yeah, who stamped their papers, Geronimo or Crazy Horse?”

With a name like mine – Urrea – that automatically becomes political; especially now, it puts a check in a certain column. It carries a history, too; the Urrea Basque mercenaries came to this continent to conquer. If you go further back, there’s a connection to the Visigoths; when I bring that up to anti-immigration folks, they don’t know what to say!

But I’m also part Yaqui (an Uto-Aztecan indigenous civilization). I’m both invader and invaded. I accept that.

This is why the story is so important. We need the poets – the women, the indigenous population, the voices that need to be heard. Because when you arm yourself with information, story and language, what can anyone else do to you?

The other part is that it’s not about “The Wall”; it’s about what separates me from you, and that extends beyond the border. When I’m giving speeches, I can see the fence built throughout the auditorium – I ask, “What about liberals and conservatives? What about Trump lovers and haters? What about Black Lives Matter; LGBTQ; Muslim, Evangelical, Jews? Can we love and hug each other?”

There are fences everywhere. I feel a calling to be brave enough to go to a stranger, someone not like me at all, and embrace them as a brother or sister. The borders separate us from each other, and if we don’t find a way to put aside our differences for the greater common good, we – and the planet – all die.

Your work draws heavily on specific geographic locations. What is the significance of place in storytelling?

We often don’t see the sacred journey we’re on because of where we’re at in our lives. We’ve done bad things, we’ve failed – but so have others. I know all about hard times and living in difficult places.

For years, I worked around Tijuana with a relief group for the poor after my dad died – it felt like nothing mattered after I lost him. And through that time, I felt the intimate depths of what it meant to reach a rock bottom with others around me.

It was from there that I was hired to teach writing at Harvard. That was a volcanic eruption; I had never been to the East Coast but all of a sudden was thrust from working in places like Tijuana garbage dumps, prisons and ranches for immigrant children into New England. I came to Colorado later to do my M.F.A., too; it was in the Rockies that God and I actually finally spoke, in some weird, wonderful way.

Everywhere we go changes us. Yet, there we are – we carry that inside us, and in turn that makes it sacred.

The place is the story inside yourself; we live by that and are stories ourselves. Those are blessings, intellectually and spiritually, causing us to start rethinking what the idea of place means – just look at Emily Dickinson, who was famously reclusive and wrote largely from her bedroom but was a monstrous talent.

Wherever you are is sacred because you’re there.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers?

You’ve got to fill your pen with love or don’t bother picking it up.

I get some guff from saying that, as people push back because of the current political situation. But like Eudora Welty’s sentiment, I believe out of love you can speak with pure fury; it’s an action. That means doing the work of witnessing: of injustice, of nature. Of you and your own family’s journey.

There’s a huge canyon between what we think of as successful writers and you sitting down to do the work, but it’s all about putting forth an eternal document of what you’ve seen, felt and thought. But it’s our duty to tell our truths artfully – we’re here to save the world, not destroy it.

The Richard T. Castro Distinguished Visiting Professorship takes place Oct. 25 from 9:30 a.m. to 7 p.m. in the St. Cajetan’s Event Center. In addition to Urrea’s keynote, panel discussions with students, immigration experts and community members will take place.