Saving Colorado’s creative voices

Two Roadrunner grads are on a mission to preserve our other natural resources: community stories.

What is the voice of a place? Who determines that? And how does it sustain across generations?

Those are the questions two alumnae set out to answer. And they’re doing it with an applied interdisciplinary foundation they forged at MSU Denver.

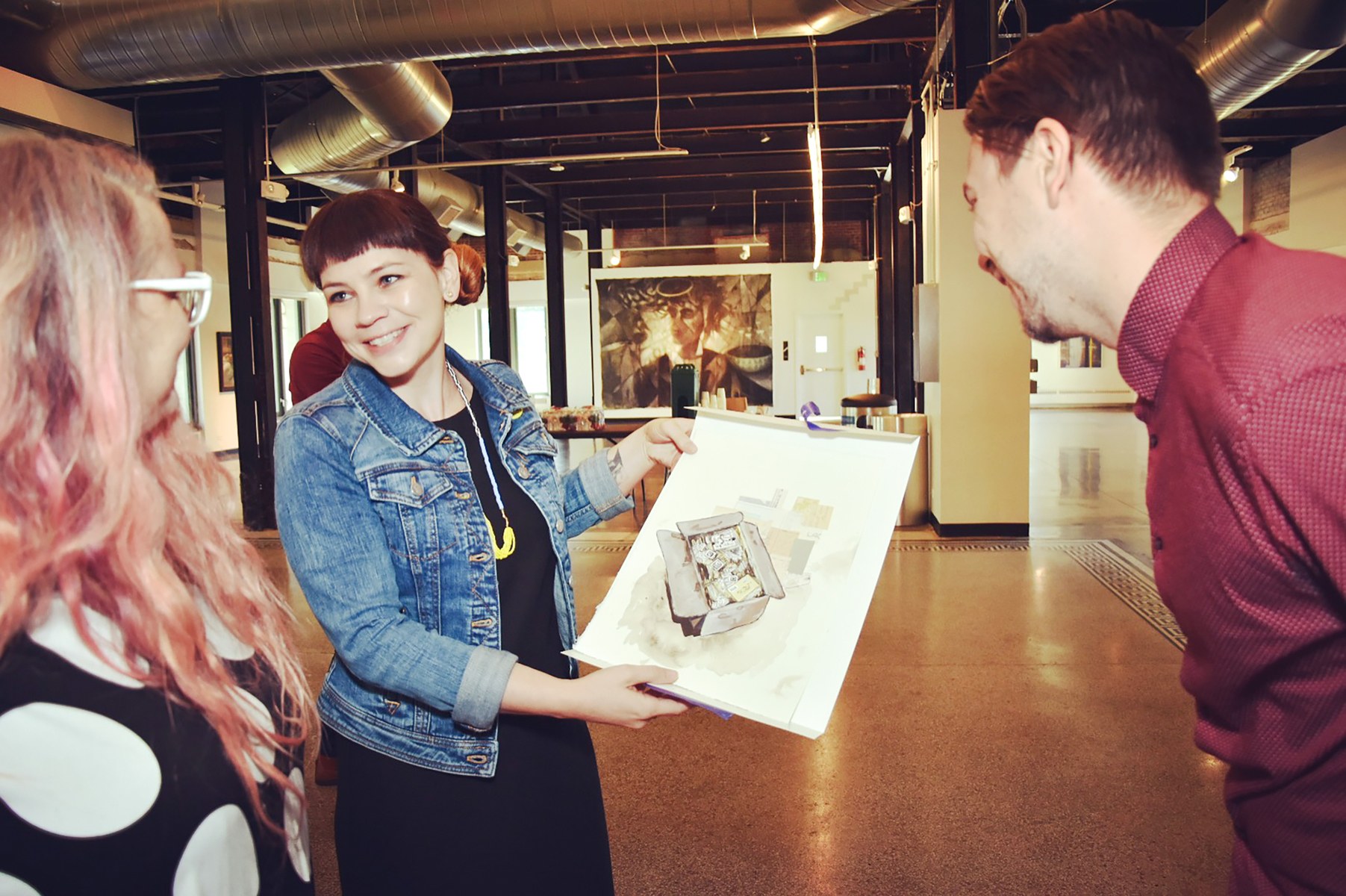

This inquiry was front and center in the recent “Archives as Muse” project. Eight artists, including 2010 English literature graduate Elyssa Lewis, created work from their research delving into various archival and museum repositories across the Front Range.

Along with a one-night program at the McNichols Building, the resulting exhibitions were on display at Leon Gallery, a contemporary art space on the border of Denver’s North Capitol Hill and West City Park neighborhoods.

With the city’s rapid growth, it’s an area that’s no stranger to change. And, fittingly, it’s a way to stage a conversation on the impact unbounded gentrification can have a community.

When it comes to the stories of those communities, too often they’re erased without any record for future citizens.

That’s where Jessie de la Cruz comes in.

“What’s going to happen to the music and murals of a place, the voices of residents who may get pushed out?” asked the 2008 graduate with an individualized degree program in museum exhibition design and art history.

As archivist and digital collections manager at the Clyfford Still Museum, de la Cruz maintains the meticulously detailed notes, correspondences and materials from the late luminary of abstract expressionism.

“Working at the museum really inspired me,” she said. “As an archivist for a single artist who’s been deceased for 37 years, I started wondering who was actively preserving the work of living artists.

“In 20 or 30 years, how are we going to understand who the creators were – what they had to say?”

That was the impetus behind de la Cruz’s launch of ArtHyve, which she describes as a crowd-sourced memory bank.

“Archives celebrate the human side of creation,” she said. “It’s layered, multidimensional and personal – whereas sometimes museums put artists on a pedestal and they become godlike, losing their flaws.”

Incorporating a do-it-yourself ethos, the group catalogues entries into a type of time capsule for Denver’s creative community. And by not focusing exclusively on mainstream artists, otherwise marginalized voices are included as contributors to the record.

For de la Cruz, who is also a board member for the Society of Rocky Mountain Archivists (SRMA), it’s more than preservation – it’s about tapping into the promise of now, something she credited her time at MSU Denver for.

“She’s always had an entrepreneurial spirit,” said Deanne Pytlinski, associate professor of art history, theory and criticism and chair of the Department of Art.

“The work she’s doing speaks to the role of artists who are there, present and part of the gentrification process – they live and see it through both sides. It makes sense to also be actively part of the issues that directly impact a community.”

An inclusive interdisciplinary approach to this is what drew Lewis to participate in “Archives as Muse,” a cultural program partnership between Denver Arts and Venues, ArtHyve and SRMA.

Because of the open nature of archives, participants were able to use materials as a source of inspiration – a muse, in other words.

“From the very first conversation [with de la Cruz], I was all about it,” said Lewis. “And Clyfford Still was a such a character; he was so intentional about his own history, leaving a trove of records documenting the creation of a historical identity.”

Initially uncertain where the project would lead, a path soon emerged: Patricia Still, spouse of the museum’s namesake, reproduced incredibly detailed miniature watercolors, tiny renditions of her husband’s oil paintings. Without the technology to snap a photo, the miniature works served as a practical catalogued reference to Clyfford Still’s paintings, which were frequently rolled up and stored upon completion.

These minuscule works, in their own right, are what piqued Lewis’ inspiration.

“She could’ve just written descriptions, but she painted these tiny renditions,” she said. “They’re lovely and intimate gestures, a reflection of her own artistic self. And she refused when her husband asked to stop making them; their quality seemingly distracted from his work.”

For the show at Leon, Patricia Still’s watercolors were projected onto a screen, behind which a shadowed Lewis read poetry inspired by the themes developed in her archival exploration.

And though there was no shortage of materials to work with, it was also what wasn’t there that led to Lewis’ humanist commentary on contemporary knowledge, linking a modernist past to our present condition.

The result was a multimodal composition and performance – or as she put it, “chimeras of creation.”

Lewis’ cross-boundary exploration has served her well, during subsequent interdisciplinary graduate study in humanities and social thought at New York University. During a creative residency in Barcelona afterward, she further began experimenting with different media, drawing on experimentation that fused history with literature and art.

Upon returning to Colorado, she’s continued to apply this practice in a grant-funded effort with Lighthouse Writers Workshop. Lewis worked with children in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood to create a public sound installation of their poetry, exploring the distance created by gentrification and its intersection with community and individual identity.

Though a circuitous road has taken her far afield, it’s one she can trace back to her time on the Auraria Campus.

“The Honors Program at MSU Denver was excellent; it had an interdisciplinary approach that really fostered curiosity and creativity,” said Lewis. “Where else can you study topics like post-colonial literature and Old Norwegian?”

She credited English professors like Marina Gorlach, Ph.D, and the late Paul Farkas, Ph.D. for encouraging her to keep asking questions, harnessing the mechanics of understanding.

And it’s this spirit of applied critical inquiry that framed the “Archives as Muse” exhibition as a prompt to see documentation as narrative empowerment, grounded in place.

“It’s important to archive Denver in this moment as the city’s undergoing transformation,” said Lewis. “Part of that is intentionally creating history, understanding the stories of those who’ve come before so we can capture the ones being written right now – and move the city forward, together.”