Perfect chemistry

How a professor’s experiment of bonding with the blind has introduced hundreds of visually impaired students to science.

Sometimes meeting someone who’s different from you can make all the difference.

Take Dr. April Hill, associate professor in MSU Denver’s Department of Chemistry, for example. In 2008, she was a post-doctoral scholar doing educational outreach at Penn State University when she met Cary Supalo, a chemistry graduate student. But Supalo was not just any student – Supalo is blind.

“When I first met him, I realized it had never occurred to me that a blind person might want to be a chemist. As an aspiring chemical educator, I felt it was something I should have considered,” Hill says. “I knew there were many other educators like me who would have no idea what to do if a blind student showed up in the chemistry lab.”

So she partnered with Supalo to create hands-on chemistry activities for the visually impaired. They combined accessible technologies Supalo had created with Hill’s hands-on activities and ran several workshops and summer science camps with help from the National Federation of the Blind.

“I saw it as a great way to learn more about accessibility issues and at the same time use my position as an outreach coordinator to promote inclusion among science educators,” Hill says.

Fast-forward to 2010 when Hill joined MSU Denver. She met chemistry professor Dr. Tom Vogt (since retired) who lived near the Colorado Center for the Blind in Littleton and had long wanted to volunteer there. Vogt knew of Hill’s work with the blind from her job interview.

“He told me we should organize a science workshop at the CCB,” Hill says.

And that’s exactly what they did – with astounding results: Since 2011, Hill has helped well over 300 blind students and upward of 100 through several workshops at the CCB.

“I think the partnership with the CCB has helped open students’ minds to the possibility of science,” Hill says. “Even if they don’t plan to pursue a degree in a STEM [science, technology, engineering and math] field, I think it’s important for all members of a society to be familiar with the scientific method and to understand the importance of science in everyday life.”

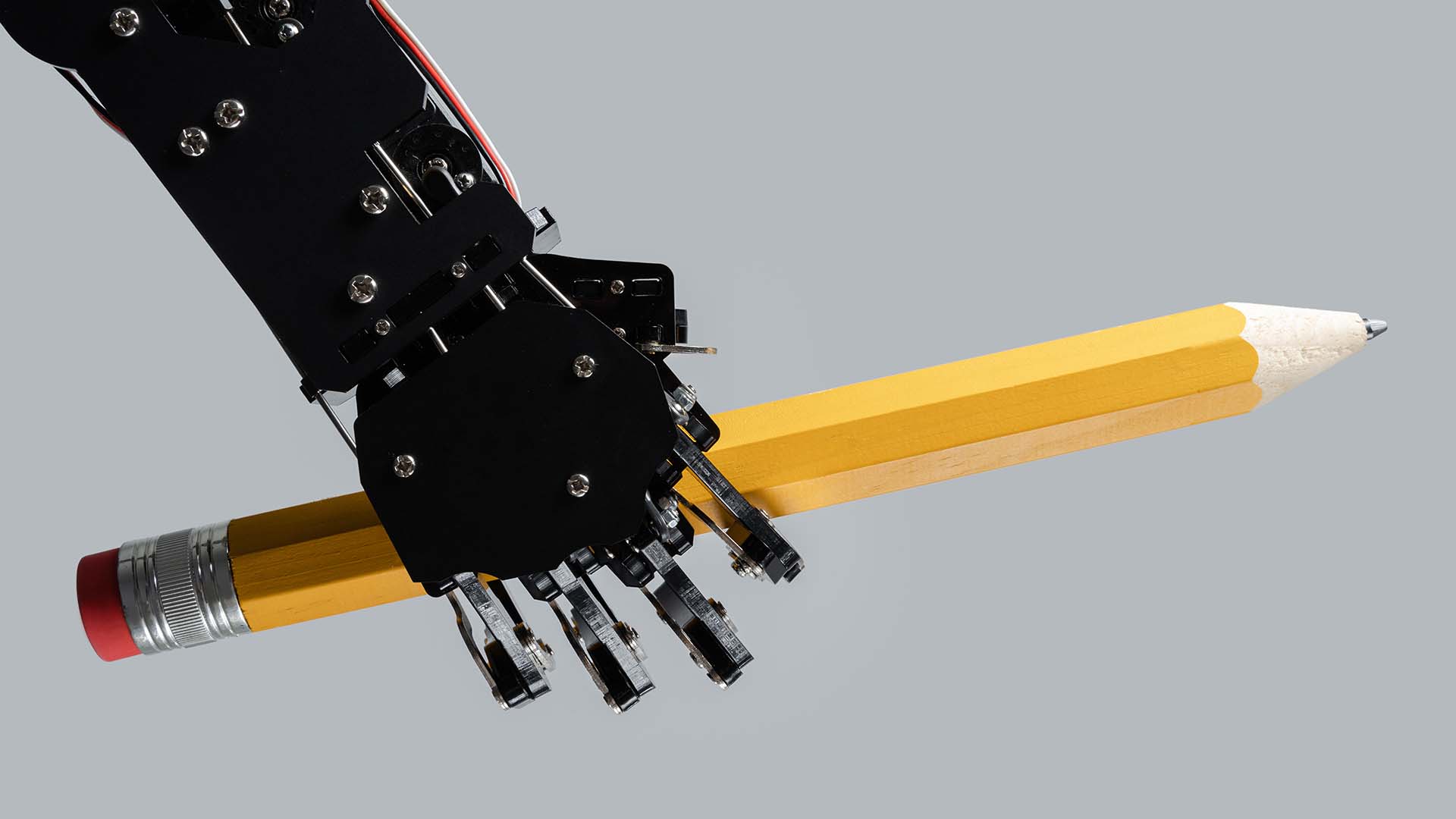

Hill says there are many tools today that are helping the blind in science classes, such as notched syringes, braille beakers, raised-bump stickers on instruments and even a device that gives audible measurements called Talking LabQuest, which Supalo created.

One of the beneficiaries of Hill’s work is Lilliya Asadullina, a blind MSU Denver student studying integrative healthcare. (Asadullina was in one of Hill’s camps as an elementary student in Pennsylvania in 2008, and they reconnected when Asadullina recently took chemistry courses at MSU Denver.)

“Dr. Hill’s kindhearted faith in the blind to do science hasn’t faltered since I met her many years ago,” Asadullina says. “She’s helped me figure out [how] to conduct experiments without having to rely on sighted assistance … how to measure out liquids independently, be more organized in the lab, and encouraged me that I can light a Bunsen burner on my own.”

Hill says another student, Tom Grushka (B.S. chemistry ’17), is a “fantastic example” of what a visually impaired student can do. Grushka worked with Hill to produce a series of videos for chemistry teachers on how to make labs more accessible to the blind.

“I believe Dr. Hill’s outreach with the CCB is a tremendous benefit to the CCB’s students and hope this relationship continues for a long time,” Grushka says. “There’s no question that Dr. Hill supports MSU Denver’s vision by opening doors for her students.”

Hill says she’s learned plenty from the work.

“It’s taught me to never underestimate a blind student’s abilities to solve problems,” she says. “People with vision impairments are natural problem solvers … everything from crossing a street to counting money. This constant practice makes them ideal scientists, and I want to encourage anyone with that kind of skill set to apply it to STEM fields.”