Meet your new cousin…

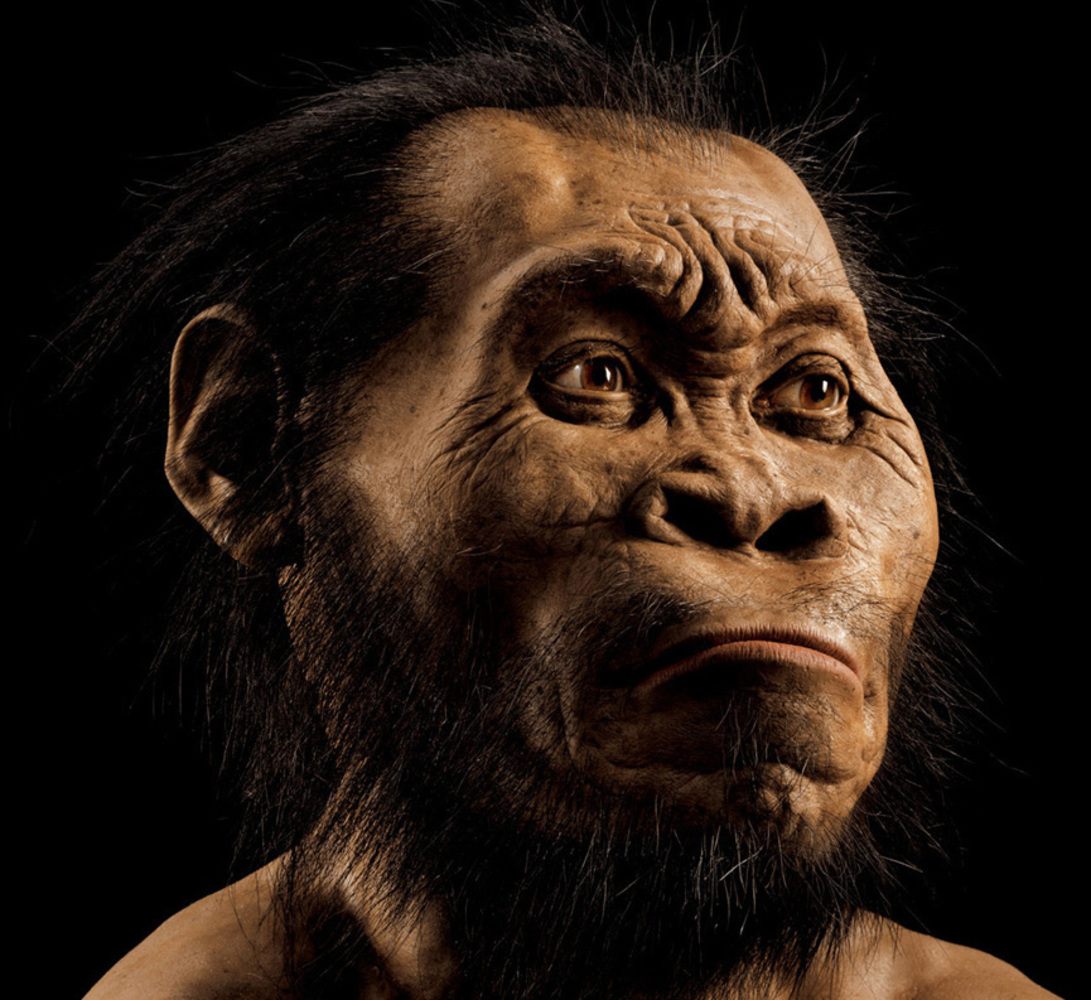

The human family just got bigger, with the discovery of a new species deep in a South African cave.

Cavers, it is generally accepted, are just a little crazy.

Many of them like nothing more than crawling into tiny, possibly deadly tunnels deep underground, in the hope of finding even tinier (and deadlier) channels that nobody has previously discovered. They might be short on space, but they’re definitely big on pioneer spirit.

So when two spelunkers converged on the Rising Star cave in South Africa three years ago, they were actively hoping to find themselves in a tight spot or two.

What they found exceeded all their expectations. While already deep underground, they stumbled across a vertical chute, just 8 inches wide in places. Undaunted (and impossibly wiry), they wriggled their way down to a tiny chamber below – and made the most astonishing human fossil discovery in half a century.

Tangled history

Everybody already knows that you, me and the guy next door belong to the Homo sapiens species. Most people also know that earlier, slightly more monkey-ish versions of ourselves, such as Homo erectus and Homo habilis, once walked the earth. Over the years, paleontologists have argued themselves to exhaustion over the specifics of exactly how and when each of these hominins evolved.

Our two cavers stirred up the whole pot again. Because in that hidden chamber 100 yards beneath the earth’s surface, they had unearthed hundreds of fossil pieces – together comprising at least 15 individuals from across several centuries – that clearly belonged to a whole new species.

And that was only half the mystery. The other question, perhaps even more perplexing, was this: How had these tiny-brained creatures repeatedly managed to find their way into such a cramped and inaccessible chamber, deep underground, in pitch blackness?

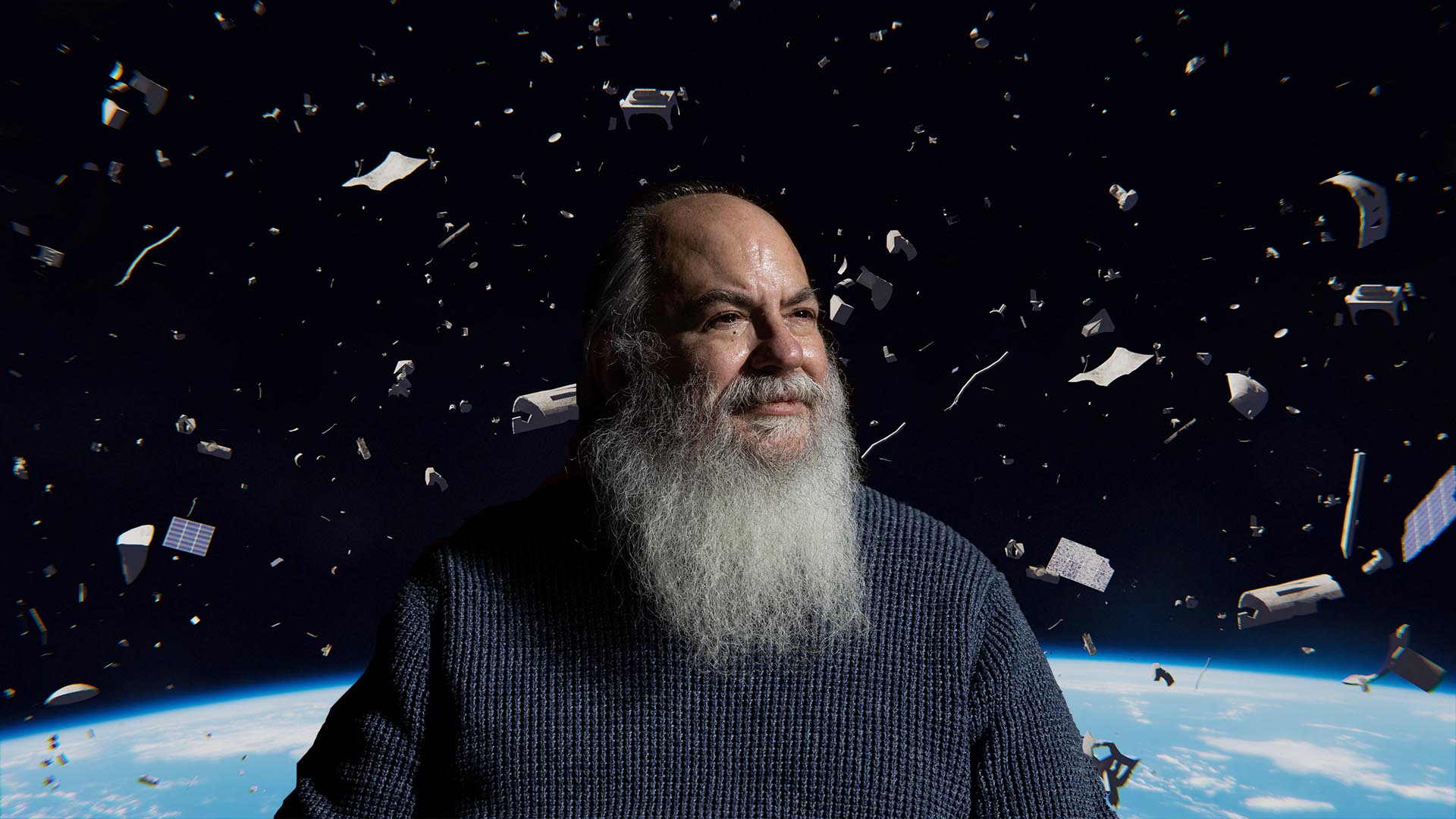

The fossil hunter

Sometimes, good things come to people who wait. And this particular once-in-a-lifetime discovery fell right into the lap of Lee Berger, an American paleoanthropologist (try saying that after a few drinks) who’d been searching for human fossils in the region for years.

Realizing the enormity of the new find, Berger immediately recruited a team of six super-skinny scientists – dubbed the “underground astronauts” – to squeeze down the chute and start excavating. Over four weeks, they retrieved 1,550 fossil pieces from just 1 square yard of ground.

Which, of course, raised the next question: How do you start to analyze and sort through such a monster collection of fossils?

Usually, following a major fossil discovery, prolonged radio silence ensues – often for years, sometimes even decades – while a small band of experienced researchers painstakingly do their thing. But Berger (known as something of a maverick in paleontology circles) instinctively knew that such a massive haul needed a radically different approach.

So he put out a call on social media looking for young researchers who had relevant experience in analyzing fossils. Many hands, he was hoping, might make light work.

Massive find

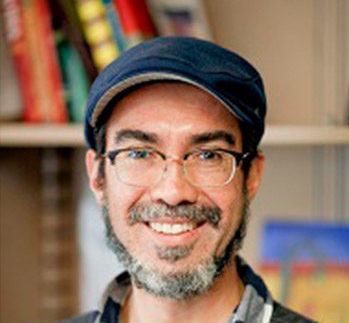

Thousands of miles away in America, Jill Scott read Berger’s message with a smile. The paleontologist (human cranial specialist, actually), has worked previously with fossil hominins and had already conducted field research in South Africa. This was right up her alley.

So she applied, they accepted, and in spring 2014 was on a plane to South Africa to join 30 other young researchers – and Berger’s own established team – for a five-week fossil fest of sorting and analyzing.

Scott, who coordinates four laboratories in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at Metropolitan State University of Denver, explains, “From the initial haul of 1,550 pieces, there were just two pieces of skeleton – tiny bones from the hand and neck – missing. That shows what a comprehensive find this was. Usually, we just find a few isolated parts of skulls and bones, so this was an incredible amount of quality material.”

For a young researcher, it was also a one-off opportunity – the paleontological equivalent of a young rookie being asked to take on quarterback duty during the Super Bowl.

“It was hugely exciting,” she says. “A major new fossil discovery like this almost always goes straight to the most senior researchers, so it was completely unexpected to get this chance so early in my career.”

Over five frenetic weeks, the team of researchers ploughed their way through the treasure trove of fossils. As Berger had hoped, the initial findings were published in just over a year – a fraction of the time it would usually take. And their new ossified friend, hidden away for thousands of years, now had a name: Homo naledi.

Family tree

In many respects, archaeologists are lucky. For them, there’s a simple rule of thumb: The deeper you dig, the older it gets. (Of course, even this doesn’t always guarantee success. Archaeologists still shudder at the memory of Heinrich Schliemann, the hapless Victorian who blasted Homer’s Troy half to bits with dynamite, thinking it was buried deeper.)

But for poor paleontologists, life is much less straightforward. The human family tree is famously wonky. Crisscrossing branches intersect with twisty roots, leading to confusion and endless debate. So while it was a fantastic discovery, Homo naledi brought more questions than answers.

Its feet, for example, were almost human – but the fingers were crazily curved and made for climbing trees. Some teeth were like ours; others had very primitive roots. Best of all, according to paleontologist Steve Churchill: “You could almost draw a line through the hips – primitive above, modern below.”

The new hominin seemed to be half-way between ape-ish past and our current selves – a conundrum full of contradictions that could have been custom-designed to give paleontologists a headache.

Biggest mystery

And still the biggest mystery remained: How did 15 individual prehistoric people get into that tiny hidden cavern in the first place?

To find out, the researchers first looked at what didn’t happen. So, the group didn’t all wander in there together. (The fossils span centuries.) They weren’t dragged there by predators (no teeth marks). Maybe the bones were washed into the cavern from higher up by flowing water? (Nope. No traces of stones or rubble.)

Having discounted every other explanation, the team started to contemplate a previously unthinkable option: burial. Incredible as it sounds, all those bodies ended up in there somehow, and the least inadequate explanation seemed to be that they were deliberately put there. But this raised yet another problem: Repeatedly reaching such a confined spot in the dark would have required light from torches, tools that were previously thought to be beyond such tiny-brained species.

To borrow Winston Churchill’s quote, the whole business is “a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.” Unsurprisingly, the paleontological community – always a hotbed of strongly held opinions – is already taking strong positions on either side of the debate.

Another chapter

Back in Colorado, Jill Scott is happily studying the new fossils and seems remarkably unconcerned about the unanswered questions. For her, that just comes with the territory.

“Paleontology is like a jigsaw puzzle,” she says. “Every time you think you’ve got all the pieces in the right place, another one pops up that shakes your perception of the overall picture. And constantly working out these moving pieces is half the fun.”

Homo naledi, like a tipsy relative turning up late at a family gathering, may have knocked over a few long-standing perceptions and upset the accepted order of things. But he’s also made the party much more interesting.

“This discovery has opened so many new possibilities,” Scott says. “And it’s going to be fascinating to see where it leads to next.”