Will ‘historical amnesia’ doom COVID-19 response?

Historians discuss how studying the impact of the 1918-19 influenza outbreak can guide the U.S. response to the coronavirus pandemic.

It had the makings of a modern-day scandal: Lacking funds to support the surge in patients during a pandemic, a health care facility wasn’t burying deceased patients or disposing of contaminated linens. Meanwhile, workers who complained about the conditions or lack of access to care for “Spanish-speaking patients” were often fired in retaliation.

This real incident isn’t breaking news ripped from today’s COVID-19 headlines, however. It was discovered by Adriana Nieto, associate professor and chair of Chicana/o Studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver, in her research of the influenza outbreak of 1918. It occurred when an insane asylum (as they were called then) in New Mexico was overwhelmed by the virus and woefully unable to respond.

“You think about the conditions where front-line public-health workers weren’t able to protect themselves or their patients, or the disproportionate impact on communities of color,” Nieto said. “It was a public-health nightmare taking place in 1918 – but some things haven’t changed to this day.”

Nieto will discuss her research May 14 during a free livestream event called “Pandemics through the ages: What history can tell us about COVID-19,” co-sponsored by the University’s Department of History and Denver Project for Humanistic Inquiry.

WATCH “Pandemics through the ages”

Examining our current COVID-19 pandemic in the context of history is absolutely critical, said Adam Graves, professor of philosophy at MSU Denver and director of D-phi.

“We’re not just talking about a failure in policy – we’re facing a crisis of understanding,” he said. “Studying the humanities can help us shed light on how to respond to the present by looking to the past for clues.”

Then and now

The local impacts of the influenza outbreak were overwhelming. During the height of that epidemic, Denver faced about 1,500 deaths in a four-month window; adjusting for today, that would be akin to adding 12,000 to 15,000 more deaths in the next few months, said Stephen Leonard, professor of history at MSU Denver who is also presenting at the May 14 event.

“It was devastating,” he said. “In 1918, the public health care system was underfunded and totally overwhelmed when the more deadly second wave of the flu hit later that year.”

Though much has changed in our understanding of epidemiology since the outbreak, there are many parallels to today’s COVID-19 pandemic, Leonard said.

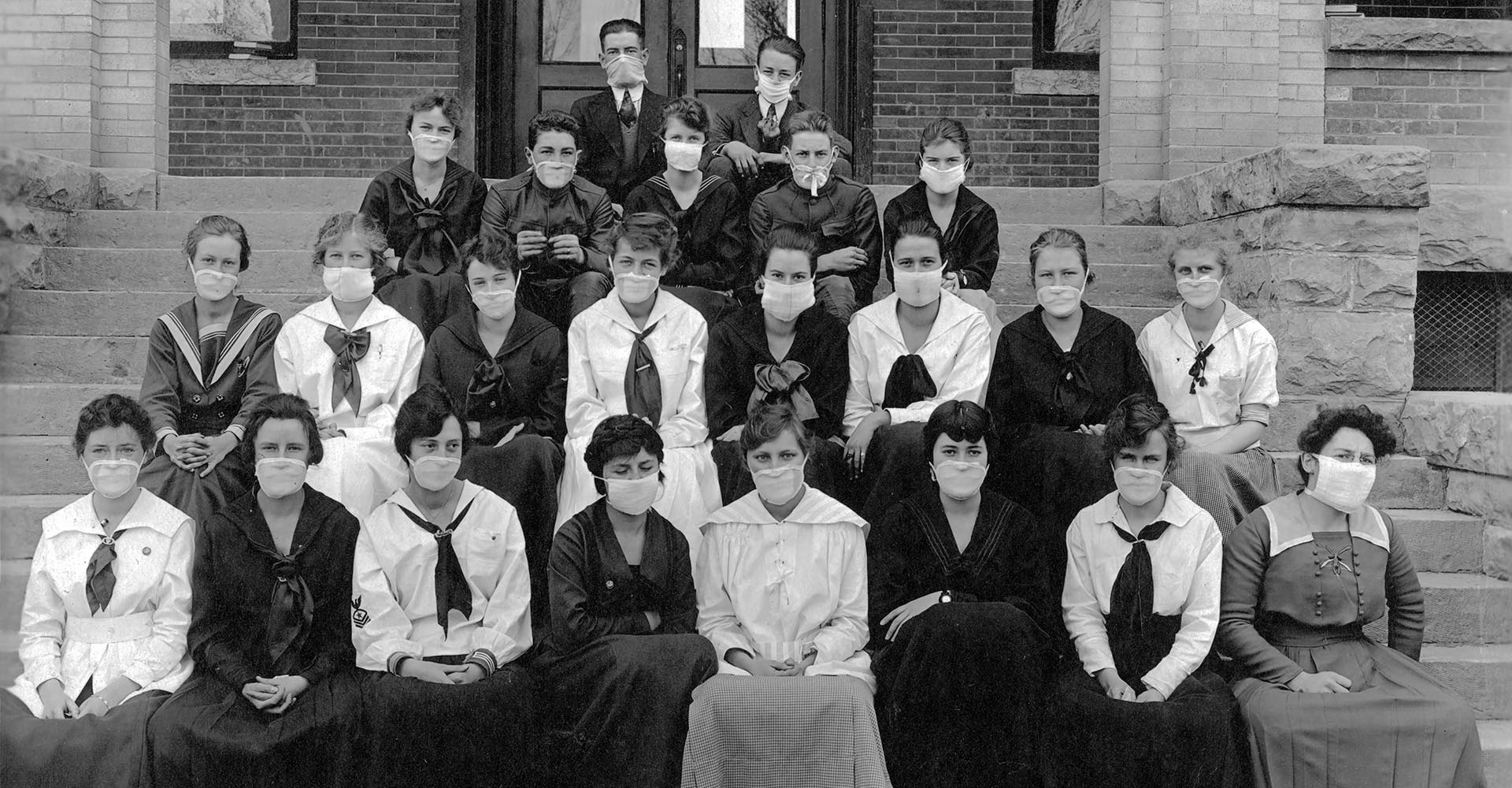

From previous encounters with diseases such as tuberculosis and “the grip” (now known as influenza), people knew they were dealing with a highly contagious respiratory illness. As such, masks were widely adopted, as well as advice to “not spit on the sidewalk,” he said. A modified form of social distancing was adopted but not to the extent we know it today; it was not enough to keep the underfunded public-health system from being overwhelmed.

Another similarity, Leonard said, was the precarious balance between a concerted effort to blunt the health impact of the pandemic and mitigating damage to the economy.

Denver’s health manager issued an order shutting down schools and theatres in early October 1918, which stayed in effect for 35 days before the theatre owners successfully fought to reopen. The subsequent spike in deaths shut things down for much longer, and the outbreak didn’t subside until 1920.

“Many people didn’t want to listen to the medical advice, limited as it may have been,” Leonard said. “They were given accurate information regarding health precautions but didn’t follow it to the degree they needed to for it to make a difference.”

Leonard acknowledged the ubiquitous tendency to fall prey to things such as confirmation bias and antagonistic media (not to mention those attempting to profit off of misfortune or uncertainty by peddling unproven curatives). He added that it’s precisely because of that that combating preconceived notions through critical inquiry can literally be a matter of life or death.

“We need more people better acquainted with the history of the past 200 years, especially in those lesser-studied areas like public health and infectious disease,” he said. “Most people are aware of the 1918 flu outbreak, but we’re failing to totally realize the danger we’re in. We’re collectively suffering from a historical amnesia. That matters because viruses don’t respect borders; they don’t care if you’re rich or poor.”

More than a data point

Nieto’s research into the New Mexico asylum incident wasn’t just academic. She discovered the case during her sabbatical research into the effects of the influenza outbreak on her family. Her great-grandmother Maria Venegas was institutionalized there during the pandemic.

Within a couple of years of the 1918 outbreak, Venegas lost her mother, husband and newborn baby to the virus. The trauma caused a severe post-partum episode that led Venegas to be institutionalized in the asylum, Nieto believes.

Geography and socioeconomics affect the lived experiences of the communities in which the pandemic spreads, Nieto said. But what isn’t easily reflected in administrative records is resiliency.

Venegas was released after a year in the asylum, at which point she reportedly walked more than 200 miles back to her hometown of La Luz, New Mexico, to reconnect with her family.

“She was a survivor,” Nieto said. “And not to downplay the death toll from it, but many people did survive to come out of the pandemic to have long and meaningful lives.”

Considering the current pandemic through a humanities-and-social-science lens provides a depth of understanding that goes beyond aggregated cells on a spreadsheet – it’s a way to address questions of access to health and wellness, including basic needs such as food and shelter, she said.

Examining the individual, localized and community experiences also exposes underlying disparities of who has a voice at the policymaking table, Nieto said – crucial contexts for mobilizing the next public-health response when it’s a matter of if, not when, it’s needed.

“People are more than a data point,” she said. “We have all this information about infection rates and demographics, but if we don’t study the underlying human experience, we can’t understand why the statistics are the way they are.”