Too many Colorado children read below proficient levels. This new center aims to help

MSU Denver’s new Literacy Research Center and Clinic offers support, including screenings and referrals, for parents of young readers.

Christina Smith felt she was not receiving needed support after her 9-year-old daughter’s teacher told her the girl had scored poorly in phonics on a standardized test of reading skills and suspected she might be dyslexic.

“She recommended some testing but had given me no direction nor resources or anything to get me going other than to talk to the pediatrician,” Smith said. “The pediatrician said talk to the school. I was really feeling very stuck on how to help my child with her reading.”

Serendipitously, Smith’s parents attended a function at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, where they met a faculty member who was an expert in literacy. When they shared their granddaughter’s plight, she told them about a new literacy resource at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

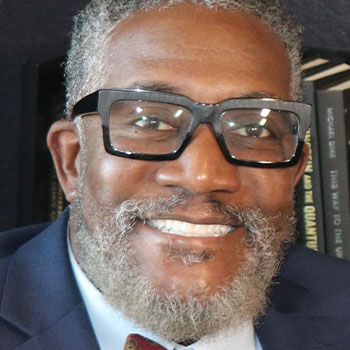

On Feb. 15, the girl underwent a bevy of tests for dyslexia at a community resource center in Aurora, courtesy of the new Literacy Research Center and Clinic. The program, which launched Feb. 1, has a twofold mission, said Executive Director Alfred Tatum, Ph.D., a professor in the MSU Denver School of Education who has been researching literacy for nearly 30 years.

“The goal of this research center is to do what we can to ensure that fewer and fewer students are being underserved by literacy instruction in this state,” Tatum said. “While we’re conducting statewide research, we will also provide direct clinical services to students and adults who may want to identify if they have a reading difficulty.”

Smith’s daughter was the second child screened in the program, he said. “We write reports for parents and provide instructional recommendations and language they can use to advocate for their child in the schools,” Tatum said.

Proficient literacy rates for school-age Colorado children are dismal but about in line with the rest of the U.S., Tatum said. For example, he added, about 56% of Colorado students in grades three through eight read below a proficient level.

There are multiple contributing factors, he said. “One, it could be caused by instructional forces and factors,” he said. “Two, it’s based on literacy authorizations. As a nation, we have created proficient reading as our ‘ceiling.’ We continue to justify reading difficulties as something that’s normal and expected in the society.”

RELATED: Colorado students are struggling with literacy

In addition, Tatum said, “We have not figured out ways to move students at faster rates to get them to read at advanced levels or exceed state and national expectations. It is taboo to even talk about the highest levels of reading in this nation, despite the large numbers of dollars that are allocated across all states.”

Tatum envisions that the research conducted by the LRCC will serve as a statewide resource to help guide educational policy and practice around literacy.

“Reading difficulties are pervasive across the economic continuum, but we continue to write articles that say that if you’re in a certain geographic location or school type, there’s an assumption that you’re going to have higher levels of reading and writing,” he said. “But that’s not the case. Students from high-income and low-income homes experience reading difficulties.”

On the clinic side, or service arm, Tatum hopes to provide direct support to the parents of children who are having trouble reading in the form of screening and providing referrals to additional resources.

For Smith, discovering the LRCC put an end to a frustrating quest to help her daughter. Smith, who had been diagnosed as dyslexic in college, had an inkling her daughter might have some problems with reading.

“She’s a very slow reader, and she has some speech difficulty making certain sounds,” she said. “I knew that much, but she reads age-appropriate books at home with us and so I wasn’t fully aware of just how behind she is.”

Getting the results of the classroom reading test without any follow-up about what to do next was frustrating, Smith said. “As a parent, being told that there’s an area of concern but then not really being provided tools or direction, it’s really hard,” she said. “I’m not an educator, so I didn’t know where to go or what to do.”

In addition to evaluating her daughter’s reading proficiency and comprehension, the LRCC team offered some practical steps to help, she said. They included having the girl read nonfiction to expand her vocabulary and orally providing her with a sentence to write to work on her writing skills and punctuation.

“Having no guidance is really stressful,” Smith said. “To have something like this program, where they are experts in that space and want to help, providing resources is really critical and honestly a huge relief.”