Maya monuments speak in signs — and now we understand them

Anthropology professor’s groundbreaking research deciphers hand gestures in writing and art as dates on an ancient calendar.

When Richard Sandoval, Ph.D., visited Copán, an ancient Maya archaeological site in western Honduras, he noticed something unusual about the way hands were depicted in the elaborate sculpted representations of rulers and deities.

“I was like, ‘Wow, that looks like sign language,’” said Sandoval, an associate professor of Anthropology at Metropolitan State University of Denver. “I came home from that trip and did some literature research on what’s going on with the hands and found little. Most of it basically implied that it’s a difficult problem — maybe an impossible problem.”

Sandoval, who had done his doctoral dissertation on the dual use of speech and signing among the Arapaho, was uniquely suited to recognize the significance of what he was seeing. So he set off on a six-year scholarly quest that led to a major new discovery about Maya writing and art.

In a newly published paper in Transactions of the Philological Society, Sandoval makes the case that the hand signs are akin to writing and represent numerals for four dates in the Maya Long Count calendar, which archaeologists have determined starts in 3114 B.C.

“There has been over a century of unverifiable attempts to decipher this particular script,” he said. “It is based on an Indigenous American signed language. Therefore, it now represents the only ancient script we know of that is not based on a spoken language. Also, it is likely the oldest record of a widely used signed language.”

Sandoval, who grew up with a bilingual father in metro Denver and has family roots in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, was more drawn to mathematics and physics than languages when he was younger. “At some point, through a convergence of studying computer science and being more serious about Spanish classes and really wanting to take on that challenge, I matured a little bit in my 20s and I learned about this thing called linguistics,” he said. “I got sold on this as the science of language.”

During his doctoral work at the University of Colorado Boulder, Sandoval studied the Arapaho language and became fascinated by the way speakers intermixed signing with spoken language, a phenomenon also seen among other Plains tribes. “There were indications that this thing was much older,” he said, “and that it had spread from the south. It is not well-researched or well-documented.”

RELATED: Ancient secrets unearthed in Cyprus

Sandoval first started teaching at MSU Denver in 2012 as an adjunct faculty member in Anthropology. In 2016, he transitioned to lecturer for Linguistic Anthropology before starting his tenure-track position in 2019. Over the 2018-19 holiday break, he traveled to Guatemala and Honduras with linguist Robin Quizar, professor emerita of English and founder of the Cho’orti’ (Maya) Project. It was then that he first saw Copán, with its ruins of monumental structures and elaborately carved stelae (stone slabs and pillars).

Upon returning home, he decided to learn more about Maya art and hieroglyphics. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it,” he said. “Right away, I started looking at the literature, but (I) didn’t have a background in writing systems or ancient texts or the Maya world. This was so much bigger than I ever could have imagined.”

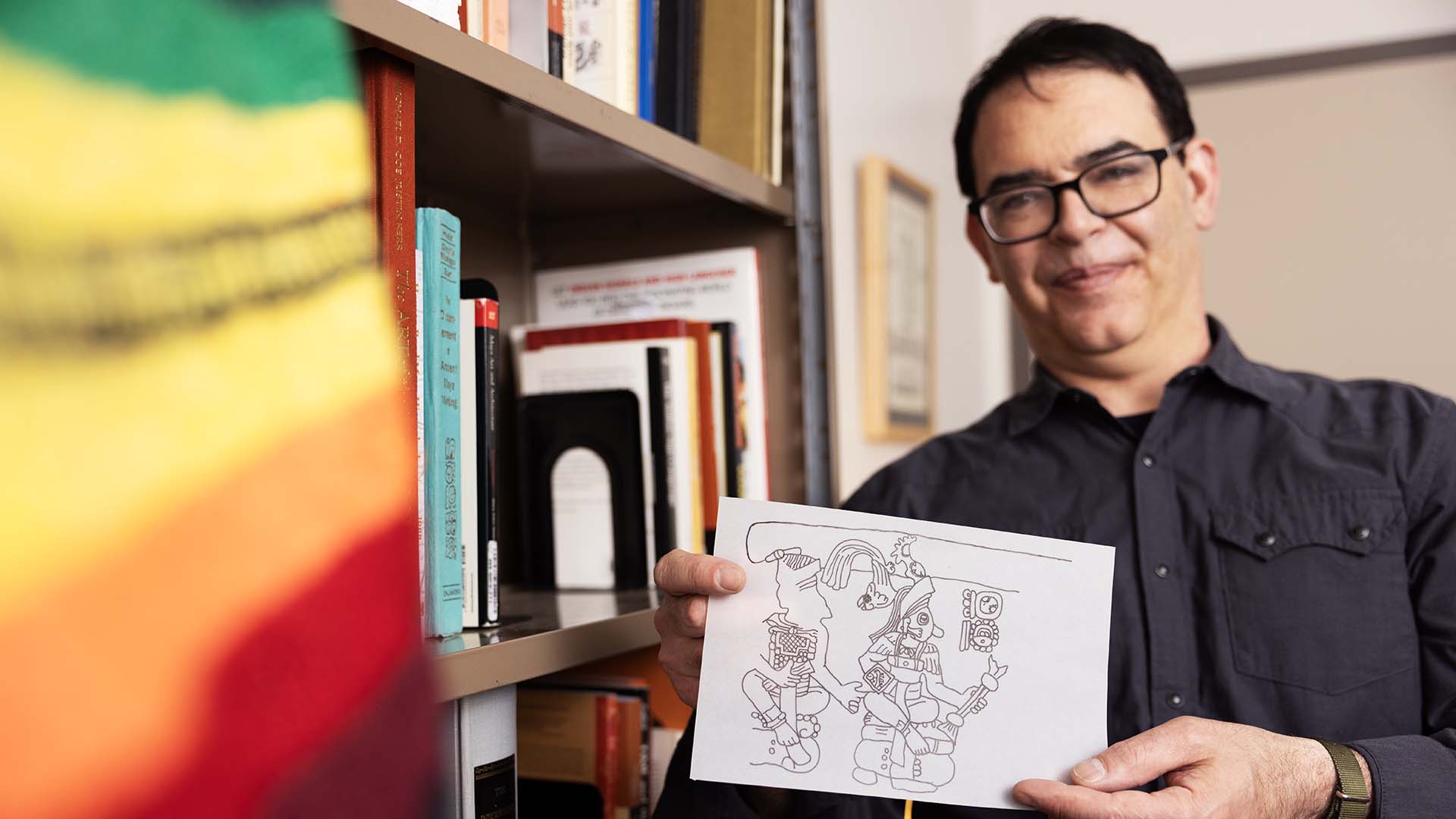

In 2019, Sandoval applied some of what he was learning to craft a new course on writing systems and scribal traditions for MSU Denver students. Later, during the Covid pandemic, he and Quizar devoted some time to studying Altar Q, a well-researched rectangular stone block at Copán covered with sculpted representations of 16 Maya rulers.

“I didn’t even have the idea in my head that that could be a key piece of that puzzle to research,” he said. “But as we started looking at Altar Q, I had a light-bulb moment: ‘Oh, there’s 16 of these people together. It’s not a single person; there’s a series of them. There’s such a rich literature on this piece, and it’s been researched in every other way. This is probably where I should start.’”

RELATED: Reconnecting with Ch’orti’

As the pandemic dragged on, Sandoval dived into the problem of deciphering the hand signs depicted in Altar Q.

“I was so excited by the possibility of Altar Q having something,” he said. “I made a little scale model of it that I could turn around and hold. I memorized the whole thing very quickly. I had various computer sheets, and I created calendrical methodology using computer-science skills so I could observe the calendar better.

“I was trying to look at it in every way, and at that point I wasn’t convinced that they were numbers. I had a hunch, though, early on.”

Sandoval made a few assumptions about the context in which the hand signs appeared, including their relationship to the accompanying hieroglyphs and the likelihood that they had something to do with the Maya culture’s well-documented interest in mathematics and the importance of dynastic periods.

“My thinking about Altar Q’s hand signs is ‘This isn’t just side information,’” he said. “These dates are actually more important in a sense than any of the dates written in the hieroglyphic text.”

Similar hand signs appear in many other examples of Maya inscriptions, which are known for the complexity of their imagery, Sandoval said. “This decipherment,” he said, “adds a layer to that complexity, another layer to something that was already kind of hard to understand.”

Learn more about Anthropology programs at MSU Denver.