From smallpox to polio: how vaccines changed the world

Since the late 18th century, scientific breakthroughs and public trust have shaped the lifesaving power of immunization.

In the battlefield of human history, no enemy has claimed more lives than disease. Wars have reshaped borders and toppled empires, but microscopic invaders have wiped out civilizations.

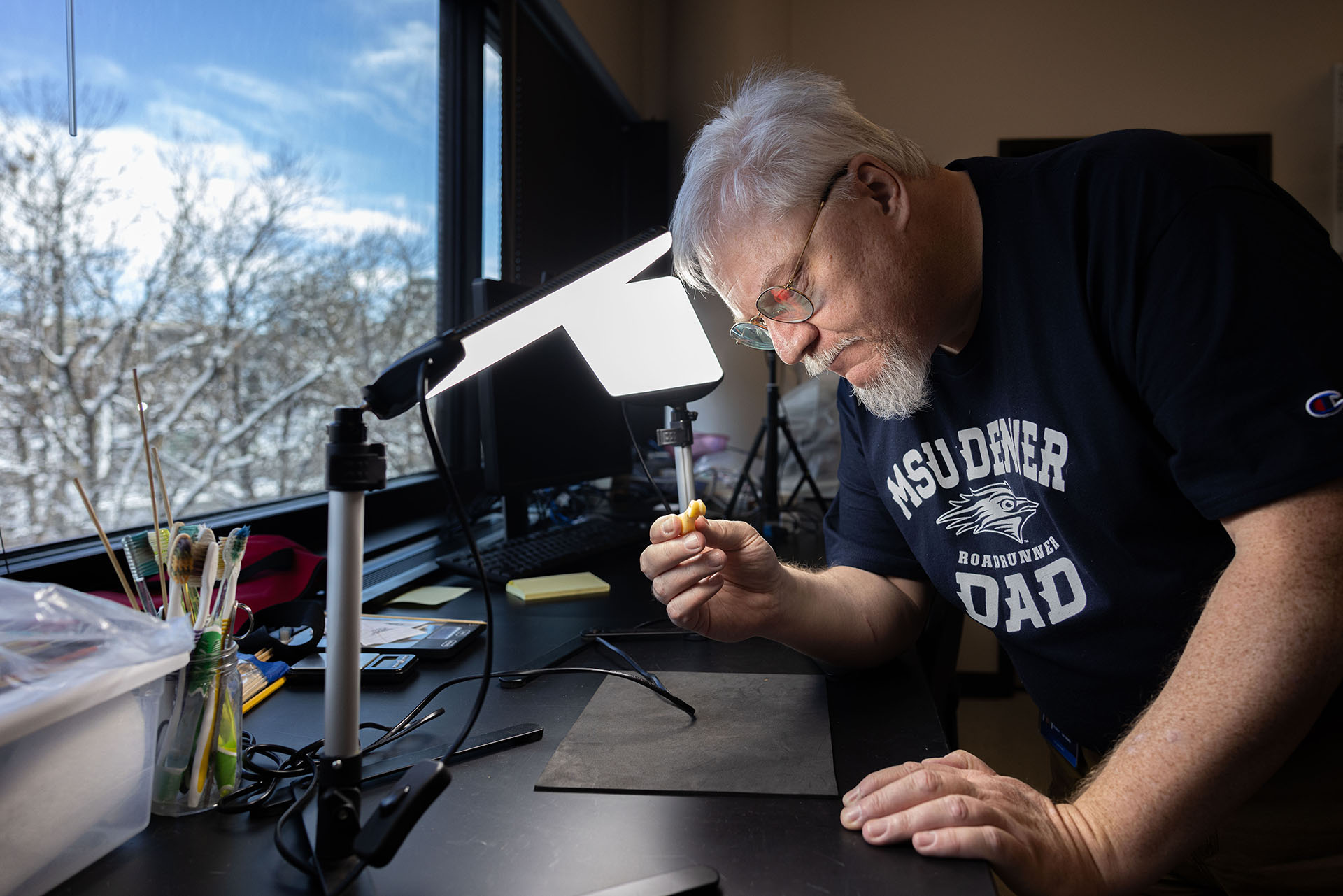

“Nuclear weapons and war have killed fewer people than disease worldwide,” said William Parker III, Ph.D., an affiliate professor of History at Metropolitan State University of Denver.

Parker specializes in molecular biology and microbiology with a focus on epidemiology and has worked at the Pentagon and in combat around the globe. He says vaccines are arguably one of the greatest weapons ever developed to turn the tide in the ongoing fight for human health.

The birth of vaccination

The concept of vaccines dates to the late 18th century, when English physician Edward Jenner noticed that milkmaids who contracted cowpox seemed resistant to smallpox. In a famous (and ethically questionable) experiment, Jenner deliberately exposed a child to cowpox and then to smallpox. The result? The child didn’t get sick.

It wasn’t exactly rigorous science — more of an astute observation and a gamble — but it worked. As a result of this experiment, the word “vaccine” emerged from vacca, Latin for cow. And just like that, medicine had its first true tool for preventing disease.

As with any medical breakthrough, Jenner’s discovery had skeptics. However, with estimates suggesting smallpox was killing as many as 5 million people each year, some people were willing to give the first vaccine a shot.

That choice, over time, led to one of the biggest revolutions in public health.

“Jenner’s vaccine for smallpox revolutionized public health because, for the first time, we had something to prevent disease rather than fight or treat it,” said Parker.

RELATED: Herd immunity explained

How the fight against polio changed public health

Despite their success, vaccines have always faced resistance. Modern vaccine acceptance took shape in the 20th century, when the military and public schools required people to be vaccinated. The polio epidemic in the United States also contributed significantly to acceptance of vaccines.

In the 1950s, polio cases surged in the U.S. As that generation of children, the baby boomers, saw friends die or suffer paralysis because of having contracted polio, Americans embraced the vaccine without hesitation.

Cost has also played a role. In the U.S., government subsidies have kept vaccine prices low or free, making access easier.

A modern arsenal against global disease

From Jenner’s rudimentary experiment, today’s sophisticated immunization technology has evolved substantially.

“Vaccines have changed,” Parker said. “Today, we have subunit vaccines, mRNA, viral vector, conjugate vaccines — the science allows us to develop them much faster.”

Faster development is crucial in fighting global outbreaks. The Covid-19 pandemic, for example, saw Pfizer and Moderna roll out lifesaving vaccines in record time, a feat made possible by mRNA technology. Unlike traditional vaccines, mRNA vaccines don’t use live viruses. They can be easily modified and are shaping the future of medicine.

RELATED: The truth about Covid-19 vaccines

The U.S. has long been a leader in vaccine development and distribution. Programs such as Covax ensure that doses reach low-income nations. The expectation, Parker noted, is that the U.S. will continue in this role because the work is expensive and complex and few countries have the infrastructure to match U.S. advancements.

Global initiatives, often funded by private donors such as the Gates Foundation, have extended these benefits worldwide.

“With the way the population moves globally, vaccinating people in developing nations has just as much impact on our safety here as vaccinating people in the United States,” Parker said.

Why vaccines matter

“The best way to win a war is not to get in one in the first place,” Parker said. “The best way to defeat a disease is never to get the disease in the first place.”

Vaccines remain our best defense against highly contagious deadly illnesses. While no vaccine is 100% effective, because different human bodies react differently, Parker offered some perspective. “One person dying is too many,” he said. “But we are all better off with a 90% solution that saves millions of lives.”

Learn about History programs at MSU Denver.