Far from the ocean, a Colorado biologist works to save coral reefs

Through her cutting-edge research, Maria Cattell opens doors for conservation of all kinds.

Over a quarter of all known marine species rely on coral reefs for survival. They also help shield coastal areas from storms and boost their economies through fisheries and tourism. Yet data from NASA shows that corals are rapidly declining, largely due to man-made causes such as climate change and pollution.

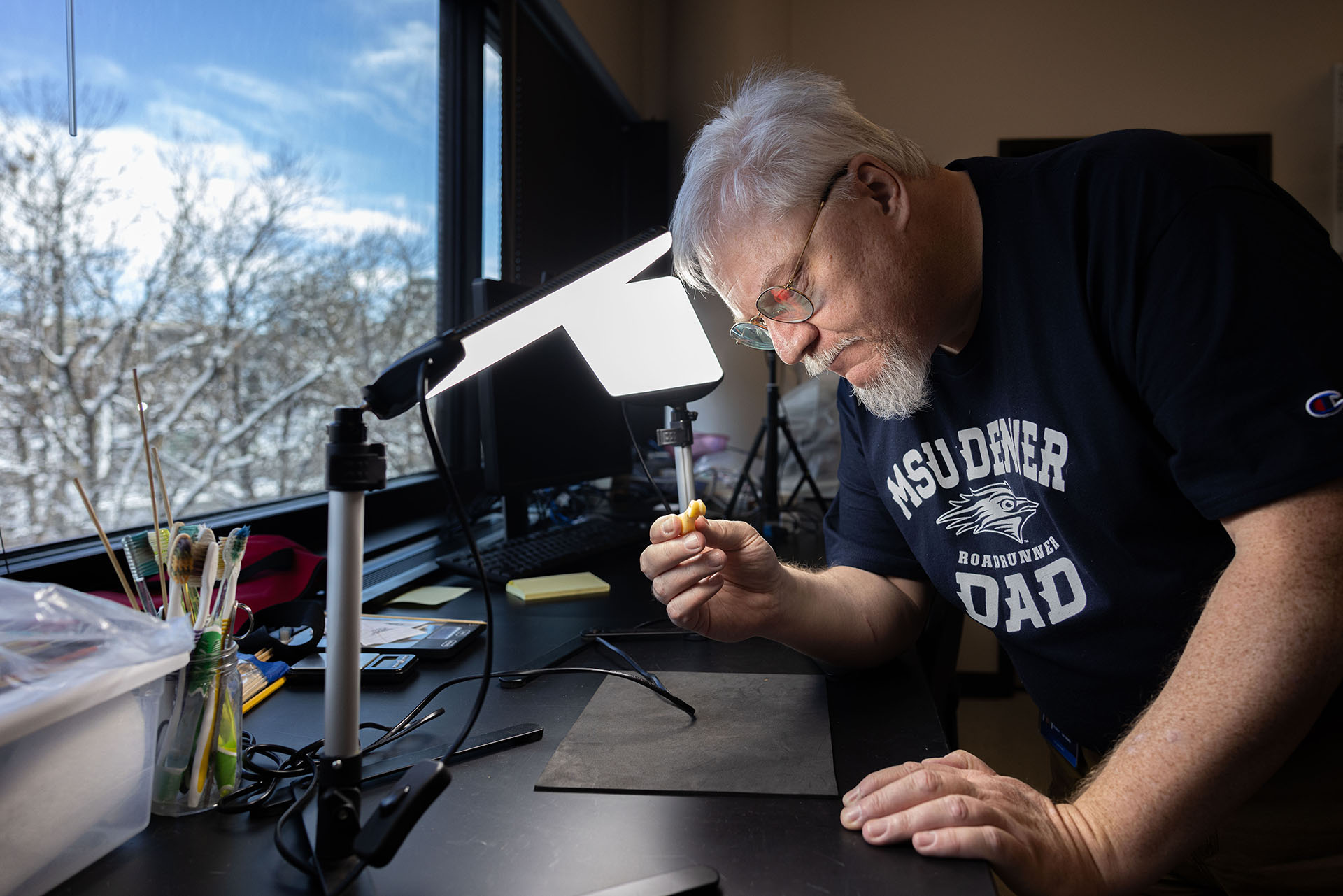

With a new study by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change predicting accelerated rates of global warming, our coral reefs may be in danger of disappearing altogether. Maria Cattell, Ph.D., professor of Biology at Metropolitan State University of Denver, is working in tandem with students to preserve corals using a novel approach: genetic modification.

“Coral is actually a symbiosis between an animal, which is the coral itself, and a photosynthetic algae,” Cattell explained. When we see a coral reef, what we’re seeing is the coral animal’s hard exoskeleton. “The corals themselves are clear, gelatinous-looking, tiny animals. The color comes from the algae that live in their tissues.

“One thing that has been happening in recent years is coral bleaching. When the animal experiences environmental perturbation, they eject their algae or the algae leave — we don’t know which yet — and that’s why the corals get that bleached appearance.”

If the coral can’t recruit new algae in time, it won’t survive the bleaching event. Cattell wants to help corals be better recruiters by adjusting their genome to produce more green fluorescent protein (known as GFP), which attracts the algae. Students will present on their findings at MSU Denver’s spring research symposium.

Saving coral reefs from extinction isn’t the only thing that excites Cattell. She’s also a tireless advocate for getting students in laboratories and conducting research early, while they’re still undergraduates, an experience usually reserved for graduate school. Undergraduate research, Cattell believes, is a vital aspect to student success, one she can personally attest to.

As an undergraduate at the University of South Florida, she conducted hands-on ecology research, and it changed the course of her life. “My advisor said, Hey, you’re pretty good at this stuff. You want to come work with us this summer as an undergraduate researcher? And that was it. I continued with that lab through my dissertation.”

RELATED: Whale tale

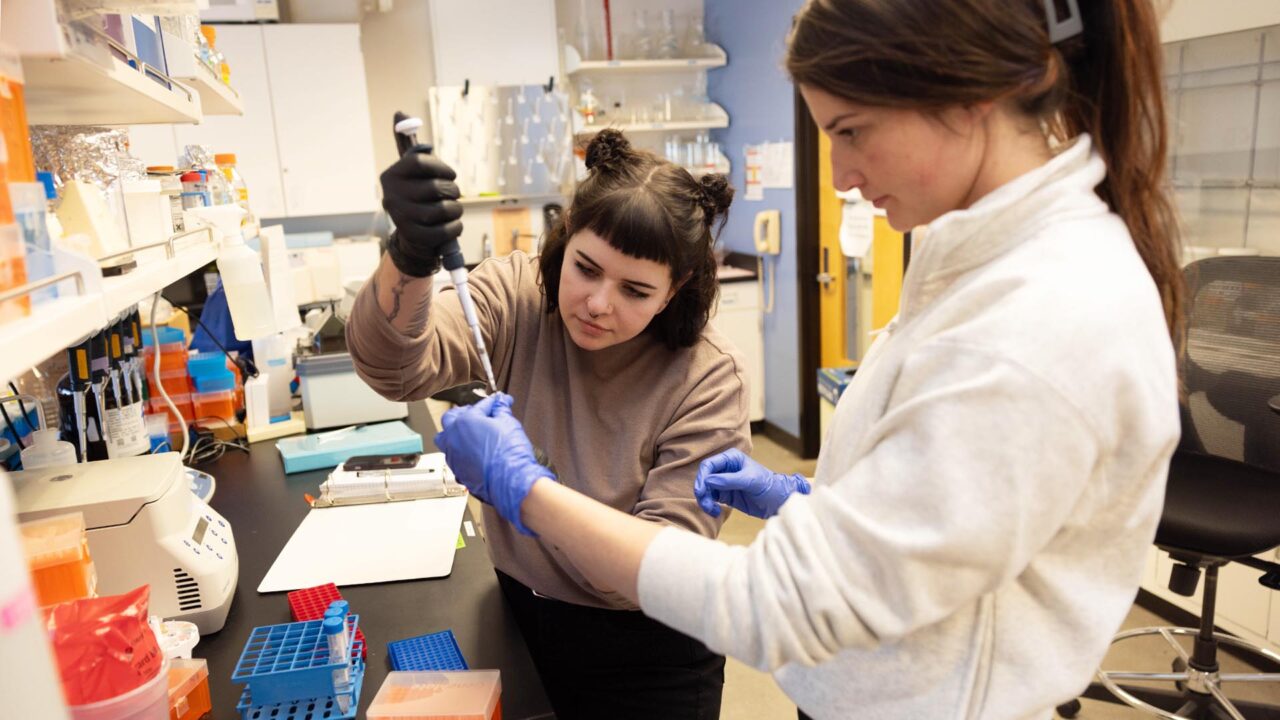

One of Cattell’s current research assistants, Biology major Meg Green, feels similar despite the initial learning curve. “I didn’t have any prior research experience, so I was a little nervous,” Green said, “but I soon learned that undergraduate research is all about learning new skills. Dr. Cattell encouraged me to try things on my own even if I thought I’d screw it up, because she knew that’s when I would learn the most.”

Hands-on experimenting in a lab can spark a student’s interest in science in a way that lectures and readings sometimes can’t, and that’s a point Cattell is most impassioned about. Green says she was inspired by Cattell’s dedication to undergraduate research.

“After graduation,” Green said, “I hope to be accepted into a Ph.D. program for marine animal/microbial symbiosis. … It’s mainly because of this research experience that I’ve been able to build the confidence to follow my academic goals and feel like a competitive applicant to a graduate program.”

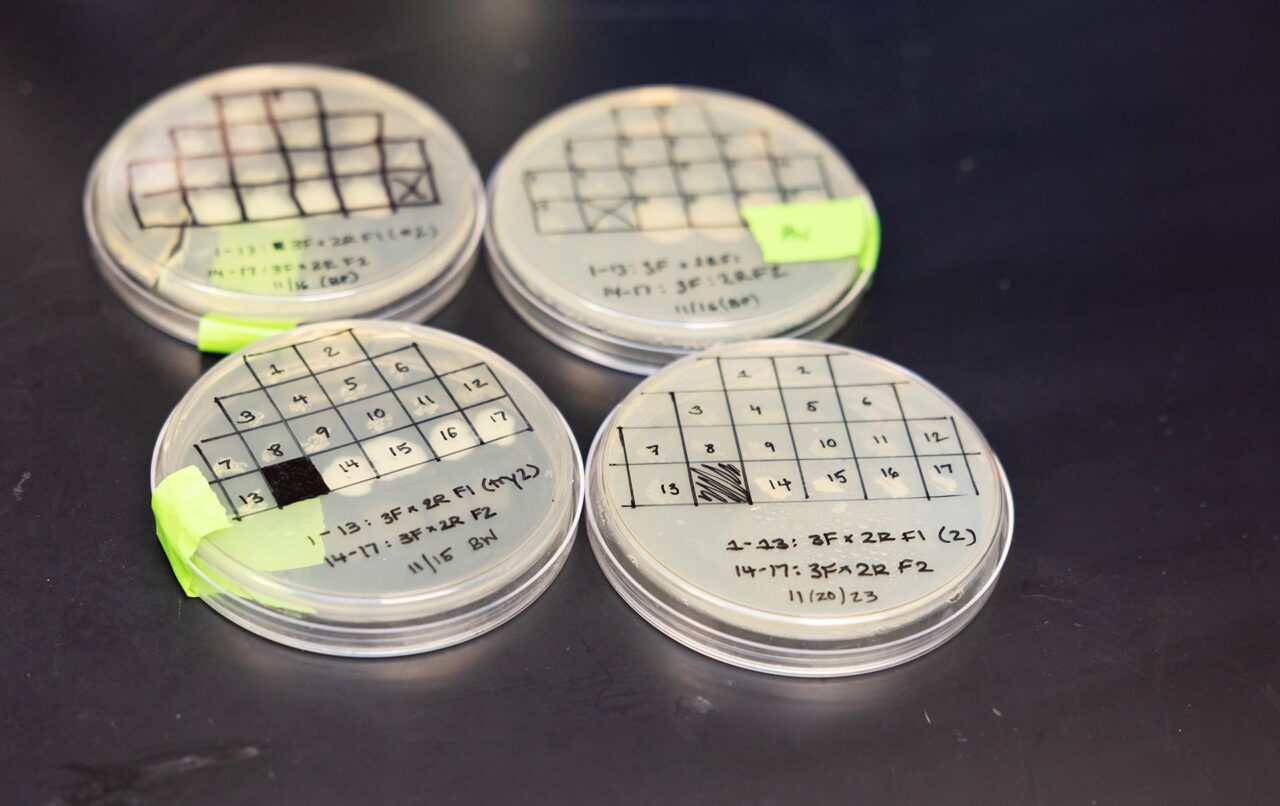

In their current research, Cattell and her students are working on sequencing the GFP gene from two species of coral, Echinopora lamellosa and Acropora millipora, and designing the gene-editing procedure they will use to manipulate the genes. They hope to test the procedure this summer.

“If we can do that with GFP, we can do it for any gene,” Cattell said. “It opens up a whole avenue for application in conservation for all kinds of animals.”