Outer space is full of our junk. Here’s what we should do about it

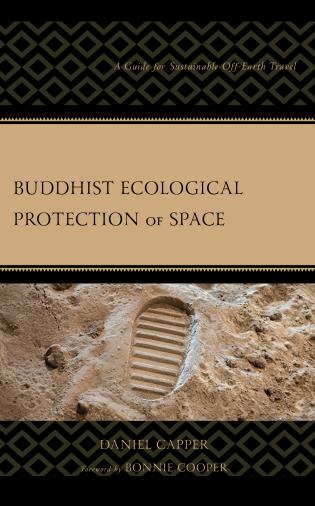

A Philosophy professor’s recent book outlines how Buddhist principles can pave the way for ethical cosmic exploration.

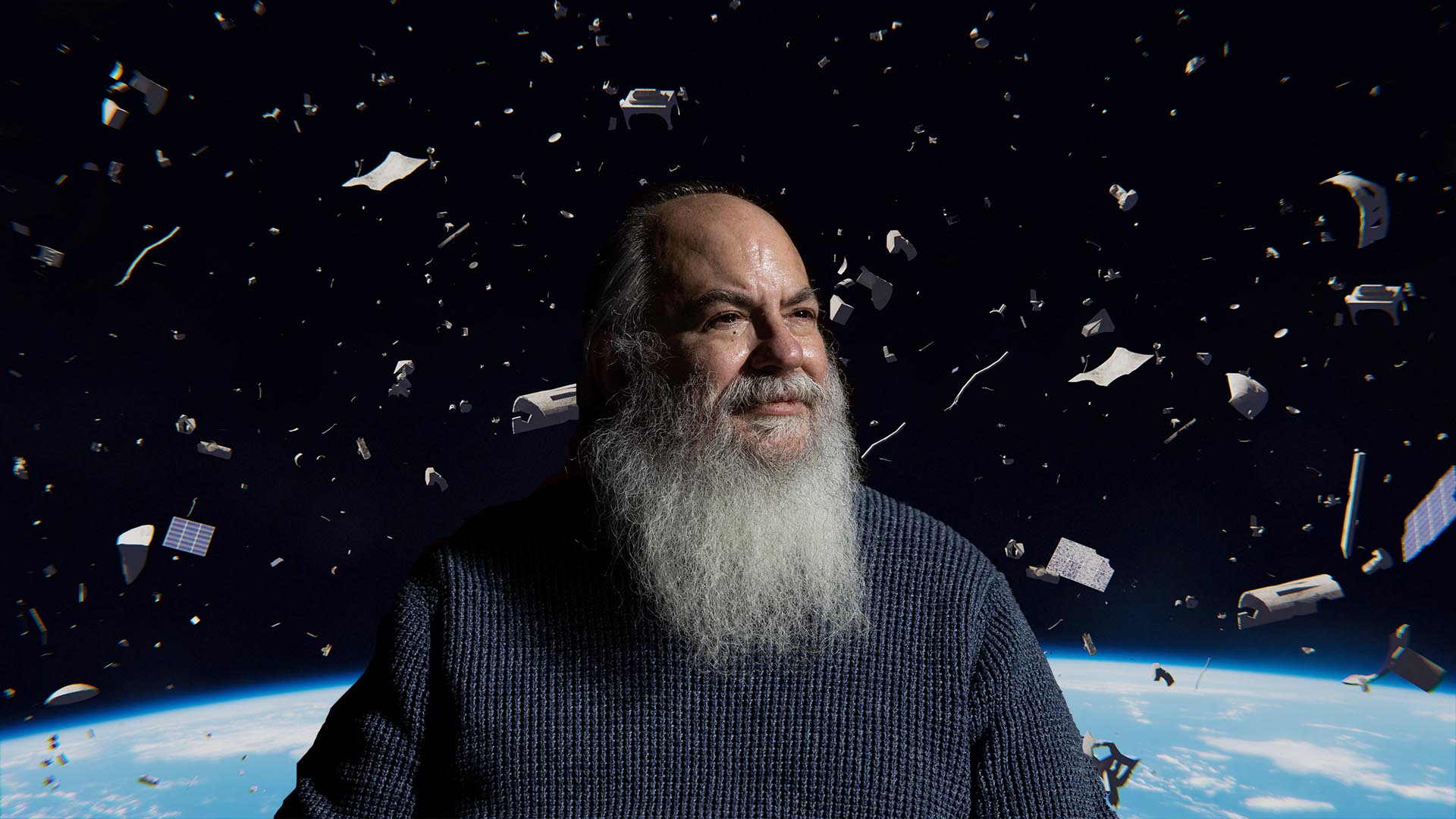

Roughly 25,000 pieces of space junk, including obsolete satellites, rocket parts and other debris, are currently orbiting Earth. Despite the threat of collision with working equipment, it’s a problem that has only recently garnered repercussions. The Federal Communications Commission in October issued the first-ever fine to Dish Network for failing to properly dispose of a satellite.

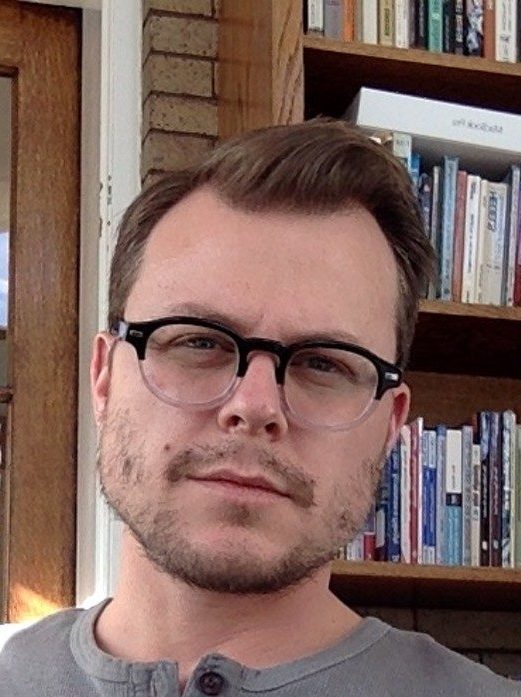

Daniel Capper, Ph.D., adjunct professor of Philosophy at Metropolitan State University of Denver, proposes that the Buddhist principle of ahimsa — non-harm — offers an ethical framework for how humans ought to conduct space exploration. Capper is the author of “Buddhist Ecological Protection of Space: A Guide for Sustainable Off-Earth Travel” and has practiced in the Zen, Tibetan and Theravada Buddhist traditions. He recently shared some thoughts about his work with RED.

What are some of the dangers that are posed by space debris?

There are hazards to astronauts in orbit, as anyone who has seen the movie “Gravity” knows. But there’s more than just that. We have all this space debris that has been building up for 70 years, and we haven’t cleaned any of it up.

One strategy NASA likes is pushing satellites farther away from Earth so that they’re not in the main orbital path anymore. That just moves them to a different place that 200 years from now could be prime space real estate, and our descendants will have to clean up our junk before they can do anything with it.

An alternative solution is to vaporize space hardware in Earth’s atmosphere. Space professionals treat this like a Magic Eraser — it’s just gone. But it’s not that way at all. With vaporized space materials, the parts made of hydrocarbons become greenhouse gases, making global warming even worse, and the other parts that vaporize end up as gases that you and I can breathe. For example, Kosmos 954 was a uranium-powered Russian military satellite that reentered in an uncontrolled way, and that uranium was vaporized. That radioactive cloud spread across western Canada.

RELATED: Astronomers have discovered ambient ‘noise’ in the universe. Here’s what that means.

Do you think treating space debris primarily as an engineering problem is too narrow a focus?

Do you think treating space debris primarily as an engineering problem is too narrow a focus?

It’s one thing to have a practical process that comes off well, but we need moral guidance for those practical processes. This is why I wrote the book. I combined the study of Buddhist texts, scriptures and philosophies with fieldwork that I did among 21st-century American Buddhists. They gave me some really interesting answers and provided the most complete moral response to space debris that we have at present.

How did you conduct your fieldwork?

Part of my research was qualitative — comments from people drive a lot of my findings. But I did provide a space environmental-ethics survey with 16 questions, and I had 121 American Buddhists from across all three branches (Zen, Tibetan and Theravada) take this survey. I also had about 80 college students representing the American general public take the same survey so that we could assess what were really Buddhist answers from those that were more general.

Was there a characteristic pattern of responses?

Regarding space debris, the first thing that Buddhists gave us was this absolute insistence that we must be responsible, and they overwhelmingly insisted that any space-debris response must care for nonhuman animals, like sea animals. No one else is talking about that in terms of ethical solutions to space debris.

Could you talk about the key Buddhist doctrines that inform this broader concern for the environment?

Buddhists taught me that in different space scenarios — space debris, mining the moon, terraforming Mars (transforming it to support human life) — they use the same construct to deal with these ecological problems.

The first part was dependent arising — the idea of the interconnected universe. This was very strong in their responses, and it really informed their way of understanding. But dependent arising on its own is not an ethical concept. Despite the fact that the universe is interconnected, we can do unethical things with that understanding if we want to.

So the Buddhists took another principle: non-harm. They allied non-harm with interconnectedness in a really interesting ethic. Intriguingly, non-harm or ahimsa classically is extended to animals and so on, but contemporary Buddhists further extend this sensibility even to rock formations on Mars.

RELATED VIDEO: Robotics Club tackles lunar-colony challenge

Did anybody surprise you with questions or considerations that you hadn’t previously thought of?

I was at the Zen Center of New Orleans, where someone said, “What we should do to protect Mars and the moon is create nature reserves.” I was so surprised that someone could come up with that idea, and it really empowered me in my further research. People were very concerned with animals who got hurt with space debris.

You’ve suggested the need for a global ethic for dealing with these problems, and you’ve turned to a 2,400-year-old religious tradition for potential solutions. Is there an audience for that among world leaders and governments?

I’m heartened to say yes. I’m delighted that some people at NASA know of my work and are encouraging me. I’ve had some dealings with folks in UNOOSA, the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, though I don’t know where this will go. But the people who actually make space decisions appear to be paying some attention to the space-ethics work that is being done now.