Renaming of Colorado historical landmarks is underway

The Colorado Naming Advisory Board recommends new designations for 28 geological sites considered offensive to Native American populations.

U.S. Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland issued an order in November declaring “squaw” a derogatory term and established a task force to rename more than 600 geographical sites across the country that have the word in their names.

“Squaw” — a racist and sexist term for Native American women — is just the latest target for renaming as the United States continues to reconcile historical names and events to modern sensibilities. Haaland also called for the creation of a complementary Advisory Committee on Reconciliation in Place Names to solicit, review and recommend changes to other derogatory geographic and federal place names.

“Place names are very powerful,” said Sara Jackson Shumate, Ph.D., a human geographer and the director of Metropolitan State University of Denver’s Center for Individualized Learning. “It’s important to rethink our landscapes and what we are valuing through these geographical names.”

RELATED: Ean Tafoya is a green-energy community leader

The federal Derogatory Geographic Names Task Force convened by Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico and the first Native American to lead a Cabinet agency, has recommended 28 sites in Colorado for renaming. All of those sites incorporate the word “squaw.”

The task force works closely with the U.S. Board of Geographic Names, which gives final determinations for standardizing the names of geographic and natural features. The board is a federal body created in 1890 that was established to maintain uniform geographic name usage throughout the federal government.

“You can’t erase history,” said Adriana Nieto, Ph.D., associate professor chair of Chicana/o Studies at MSU Denver. “Changing geological names doesn’t change our history; it reframes it. Reframing history is important because it points out the holes. Naming important places should be a way to remember or learn about important people and events. It changes what we talk about.”

Nieto said she’s hopeful the conversation is now happening at the national level. “It means it won’t go away easily like it has at a local level,” Nieto said. “A lot of credit goes to Secretary Haaland, who has created an opening for a conversation and brought the significance of names to the public eye.”

Local efforts

Jared Polis established the Colorado Geographic Naming Advisory Board last year to evaluate proposals concerning name changes, new names and name controversies of geographic features and public places in Colorado.

In September, the board made its first recommendation: to change the name of Squaw Mountain in Clear Creek County to Mestaa’ėhehe Mountain. Pronounced mess-taw-HAY, the name honors an influential Cheyenne translator known as Owl Woman.

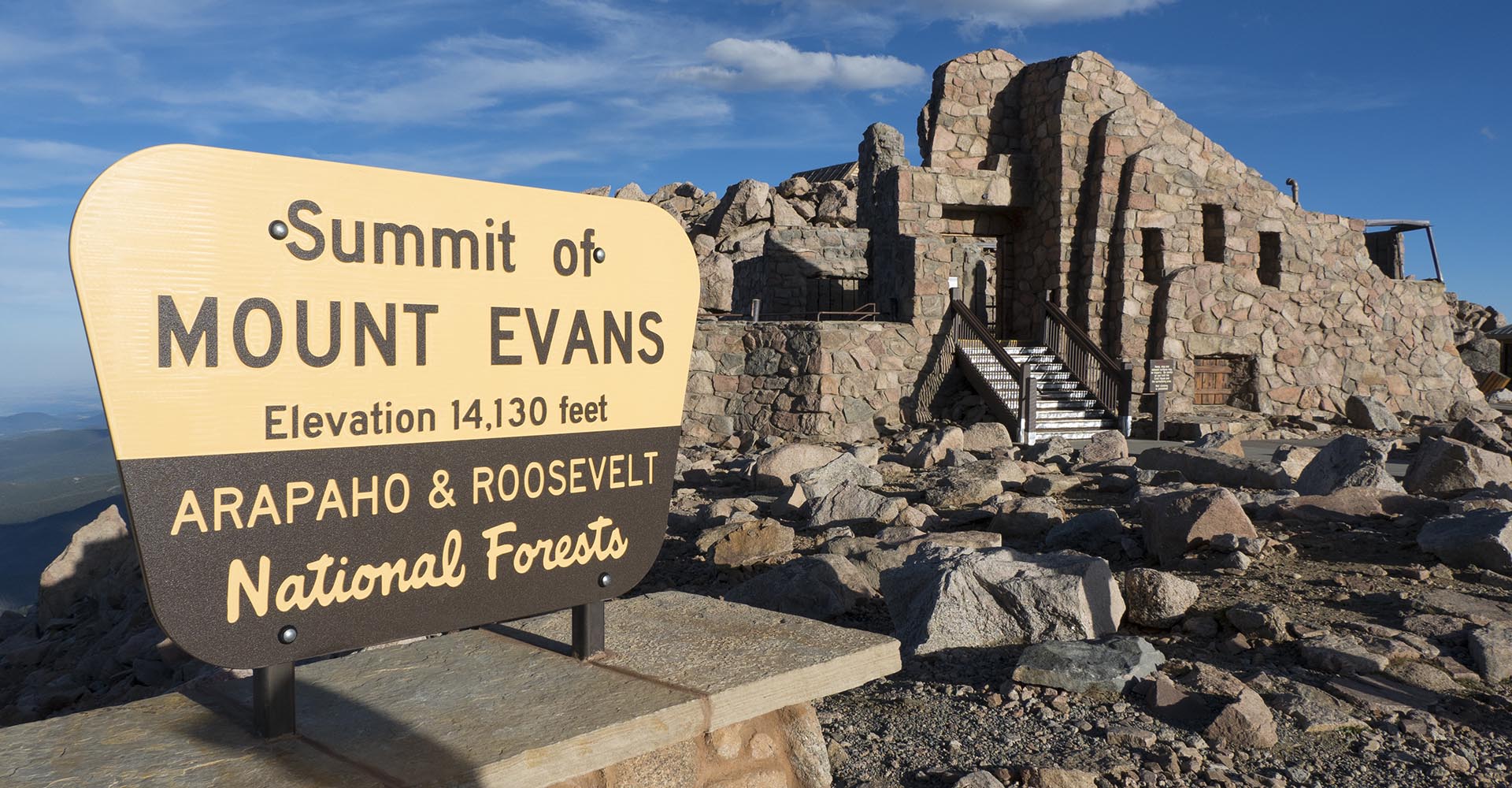

Other discussions at the state level include renaming Negro Creek and Negro Mesa in Delta County to Clay Creek and Clay Mesa, respectively; changing the name of Redskin Mountain in Jefferson County to Mount Jerome; and renaming Mount Evans as Mount Blue Sky, the name the Arapaho people call themselves.

Mount Evans was named for Territorial Gov. John Evans, who oversaw the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864, in which volunteer soldiers attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho village, killing approximately 750 people.

RELATED: How new words enter the lexicon – and the dictionary

Jackson Shumate is hopeful that renaming such a well-known site might spur conversations about past and current values.

“People vacation at these sites. If we start renaming places like Denali (from Mount McKinley) and Mount Evans, it creates an inflection point to begin a critical conversation about our past and what we value as Americans and Coloradans,” Jackson Shumate said. “Do we want the largest peak in Colorado to be named for a territorial governor who was forced to resign because of his part in the infamous Sand Creek Massacre and its subsequent coverup or something we can all be proud of?”

Mount Evans’ name change may soon be a reality. On Tuesday, the Clear Creek County commissioners recommended changing its name to Mount Blue Sky. The recommendation will go to the state Geographic Naming Advisory Board and Polis before a final decision.

Last June, Colorado legislators passed Senate Bill 116, which prohibits the use of American Indian symbols and names by Colorado public schools beginning this June. Schools that do not come into compliance by June 1 face a $25,000 monthly fine.

“These efforts are steps, albeit baby ones, in the right direction,” Jackson Shumate said. “This is scratching the surface of what really needs to change, which is how we think about and relate to one another, but it gets us moving in the right direction.”