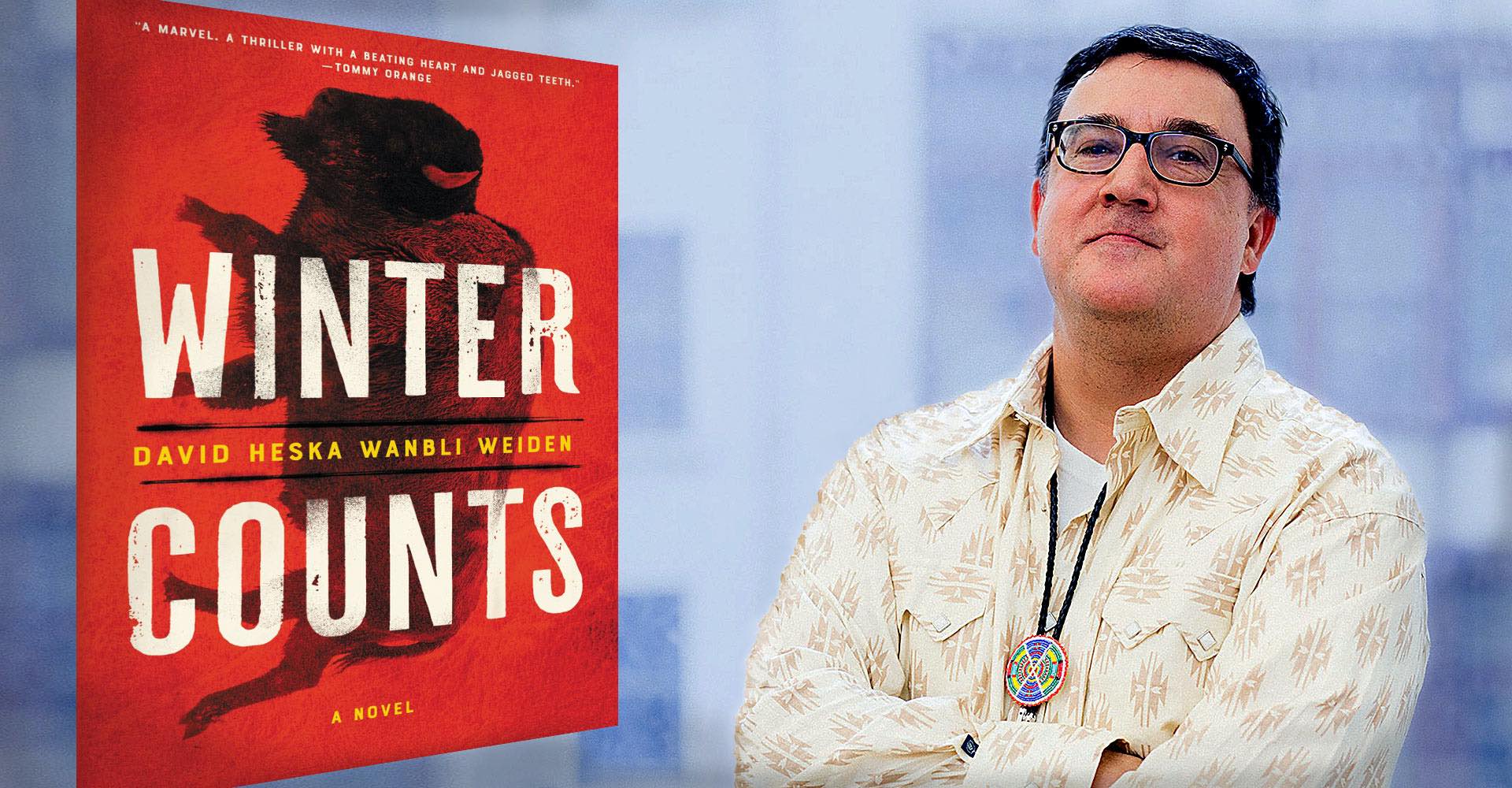

The broken promises behind ‘Winter Counts’

New crime novel by Lakota author David Heska Wanbli Weiden and a recent Supreme Court decision explore the same issue: federal law enforcement – or lack thereof – on Native lands.

Friction between federal law enforcement and Native American nations is the focus of a new novel by Denver author David Heska Wanbli Weiden and a landmark ruling issued by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The July decision in McGirt v. Oklahoma reaffirmed a nearly 200-year-old land treaty with the Creek Nation, effectively removing from the State of Oklahoma authority to enforce certain state laws against members of Native nations on tribal lands and affirming the federal government’s jurisdiction to prosecute certain crimes on those lands.

While the court’s decision upholds a federal treaty with Native nations, Weiden, a professor of political science and Native American Studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver, considers federal law enforcement’s jurisdiction on Native lands to represent a broken promise to Native Americans.

The rate at which the federal government declines to prosecute felonies referred from Native nations is “astounding,” he said.

“Child abusers, rapists, arsonists, burglars … the government is not prosecuting them for a variety of reasons, and they release these men and women to go out and commit more crimes,” he said.

The federal government’s failure to protect Native peoples is the inspiration for Weiden’s forthcoming novel, “Winter Counts,” which will be released Aug. 25 by Ecco Books, an imprint of HarperCollins.

The novel’s protagonist is a vigilante who goes after heroin dealers on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, the land of the Sicangu Lakota nation, of which Weiden is a member in real life. The fictional Virgil Wounded Horse has personal motivations to catch criminals himself after his nephew nearly dies of a drug overdose.

“What has happened on certain reservations is, maybe your kid has been attacked, or your wife has been attacked, and the government won’t do anything. So you turn to private justice. That’s when you hire a private vigilante, like my character Virgil Wounded Horse, who is based on real people,” he said.

The 2019 annual report from the Department of Justice shows that the U.S. Attorney’s Office filed charges in 788 cases of violent crime in Indian Country but declined to prosecute in 786 – 50% of referred cases. The declination rate for violent crimes in the rest of the country was 46%.

That discrepancy is magnified when considering high crime rates on Native land. The Justice Department estimates that one in every three Native women has experienced rape or attempted rape, while on some reservations Native women are 10 times more likely to be murdered than the national average.

“The reluctance to prosecute certain felony crimes on reservations is well known in Indian Country, and it has led to a virtual open season on Native women,” Weiden wrote last month in an op-ed in the New York Times.

The case that brought the issue before the Supreme Court itself could be a crime novel. In 1997, the State of Oklahoma convicted Jimcy McGirt, a Native American, of raping a 4-year-old child. In his appeal, rather than focusing on his guilt, McGirt’s lawyers argued that the state didn’t have jurisdiction, because the crime, which was committed in Tulsa, was committed not on state land but on federal “Indian Lands.” Oklahoma had owned and controlled that land for more than 100 years, but it had been promised to the Creek Nation, pursuant to treaty, nearly 200 years ago.

The Supreme Court’s majority opinion in McGirt (penned by Justice Neil Gorsuch, a Coloradan) begins by referencing that treaty and the Trail of Tears, a period ushered in by the Indian Removal Act of 1830 during which some 60,000 Native Americans were forcefully removed from their ancestral homes in America’s Deep South. The Native peoples marched hundreds of miles west on the promise that they would forever be granted replacement land in the so-called “Frontier,” which is today Oklahoma.

“On the far end of the Trail of Tears was a promise,” Gorsuch wrote before outlining the long history of U.S. relations with Native nations. He specified the law-enforcement arrangements outlined by the Major Crimes Act of 1885, which grants jurisdiction to federal courts – not states or Native nations – in trying felony crimes such as murder and sexual assault committed by Native Americans in “Indian Country.” The Creek reservation’s boundaries have been diminished over time practically but not legally, and the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the land defined in the original treaty remains a reservation, regardless of the legal complexities that could arise for the state.

“The magnitude of a legal wrong is no reason to perpetuate it,” Gorsuch’s majority opinion concluded. “When Congress adopted the MCA, it broke many treaty promises that had once allowed tribes like the Creek to try their own members. But, in return, Congress allowed only the federal government, not the States, to try tribal members for major crimes. All our decision today does is vindicate that replacement promise.”

Upholding a promise that maintains federal authority to prosecute specific crimes on Tribal land isn’t the solution Native nations need, said Weiden, who is an advocate for returning criminal jurisdiction to Native nations. His hope is that Congress will take another look at the Major Crimes Act.

It’s also a personal issue for him: The act was originally passed after the murder of Spotted Tail, a Lakota chief about whom Weiden wrote a nonfiction biography in 2019. “Spotted Tail,” a children’s book published by Reycraft, went on to win a Spur Award for juvenile literature from the Western Writers of America this year.

“Winter Counts,” the first of a two-book series with HarperCollins, is available for preorder from various retailers. It is one of the first crime novels written by a Native author to be published by one of the Big Five publishing houses in the U.S.