Let’s talk about cancel culture

Is the social-media phenomenon a way to hold power to account or a mob stifling free speech? And is it actually advancing social justice? Here's where the dialogue starts.

By now, the process is old hat: A person says or does something considered racist, xenophobic, sexist, homophobic, transphobic or otherwise offensive, and backlash on social media follows.

But when the social-media masses “cancel” a person for perceived transgressions, are they effectively advancing the causes in whose names they act, such as social justice or racial and gender equity?

Talking about what we mean when we use the phrase “cancel culture” is a starting point for keeping the focus on those causes, said Katia Campbell, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Communication Studies at Metropolitan State University of Denver. Right now, however, it seems Americans are on two separate wavelengths when it comes to defining “cancel culture.”

“From the right it’s interpretated as, ‘thought police,’ or ‘PC culture,’” she said. “The left is looking at it as standing up for justice and representation.”

Social media has allowed the country to join together based on shared values to elevate and amplify a message and created awareness of the power of representation, Campbell said.

“We’ve reduced this (phenomenon) down to cancel culture, but where do we go from there?” she asked. “Are we moving forward and advancing the discussion of justice and representation or are we creating an environment in which people are afraid to say anything at all?”

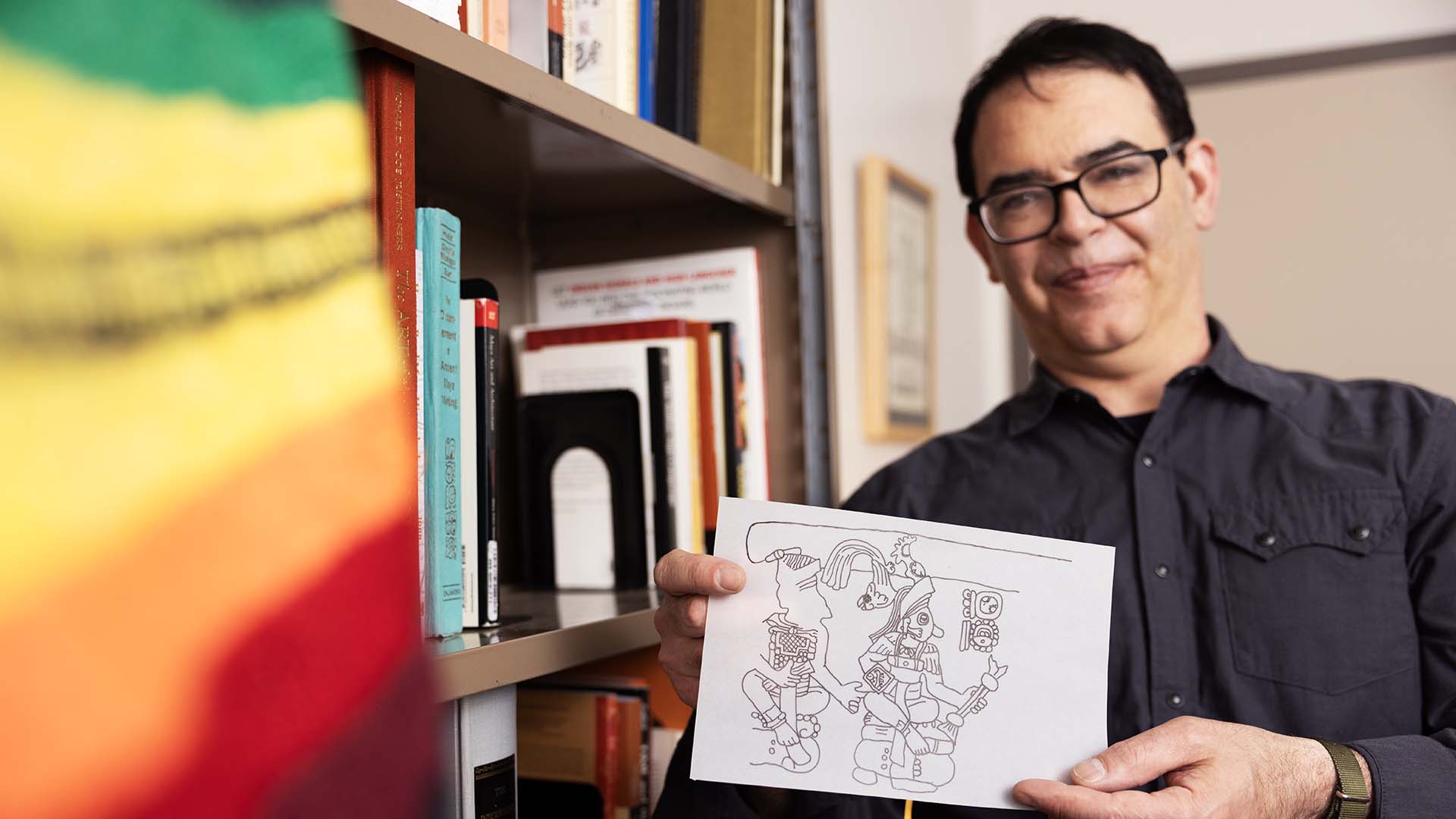

Scholars from MSU Denver explored the concept and questions it raises on Sept. 24 with the launch of the Fall 2020 Dialogue Series: Cancel Culture and Social Justice. The panel discussion was moderated by Thomas Ragland, director of student accountability and behavioral intervention in the Office of the Dean of Students and also featured Janine Davidson, Ph.D., president; Liz Goodnick, Ph.D., associate professor, Philosophy; Brendan Hughes, Ph.D., lecturer, Communication Studies; and Eunice Callejas Solano, student, Communication Studies and debate-team member.

The Dialogues Program was developed as a forum for difficult exploration and inquiry into the most pressing issues of our times. It is a joint venture between MSU Denver’s Department of Communication Studies and the Office of the Dean of Students. When it was conceived in early 2020, Campbell wanted to launch the program on the topic of cancel culture, she said. However, the pandemic and subsequent protests for racial justice moved racism to the fore, and the program kicked off in June with a panel of prominent Black scholars discussing how America talks about race in the wake of police killings of people of color.

The discussion around cancel culture and systemic racism both involve issues of power, Campbell said.

“We talk about cancel culture as if the social-media ‘mob’ is where the power is,” she said. “But when someone is canceled, does that really tackle the problems of our power structures and systemic issues we face?”

In fact, power and who wields it are critical to any definition and discussion of cancel culture, said panel participant Hughes. One definition he uses as a starting point comes from the writing of Sarah Hagi.

“She called cancel culture ‘a catch-all for when people in power face consequences for their actions or receive any type of criticism, something that they’re not used to,’” he said. “That last part is important: Most in power are not used to facing criticism.”

But the focus on holding those in power to account can also end up taking attention from those who are being harmed by that person’s words and/or conduct, Hughes said. For instance, consider the outrage over author J.K. Rowling’s recent transphobic tweets. The conversation about the harm that those comments caused to trans people has been derailed because of the immense space that the “Harry Potter” author occupies.

“Canceled people don’t get to publish letters in Harper’s,” he said, referencing a July 7, 2020 “Letter on justice and Open Debate” signed by 153 public figures, including Rowling, published in Harper’s Magazine. “It’s an example of how cancel culture gets wrapped up in a specific person or personality rather than follow the dialogic process through to address those harmed by that person or the ideas expressed.”

When cancel culture was the topic of a recent debate tournament, panel participant Callejas Solano realized how it can have the unintended outcomes.

“I was assigned to argue that cancel culture is an ineffective tool,” she said. “As I dug into it, I was surprised to find myself agreeing that cancel culture often didn’t advance justice beyond statements on social media.”

Younger, social-media-savvy generations are aggressively canceling individuals from older demographics and celebrities when they cross lines, Callejas Solano said. But the act of canceling a person often ends up bailing them out from doing the hard work of learning, changing and apologizing to the community they harmed.

It’s hard work,” she said. “And maybe we should allow those people to do that work so things change. But at the same time, even as we allow people with power to do that work or accept their apologies, we don’t have to continue to buy their books, listen to their music or watch their movies.”