First-gen forward

College students who are among the first in their family to pursue higher education often require additional resources to succeed. Now, Colorado first-gen students are taking their requests for additional support to the state Capitol.

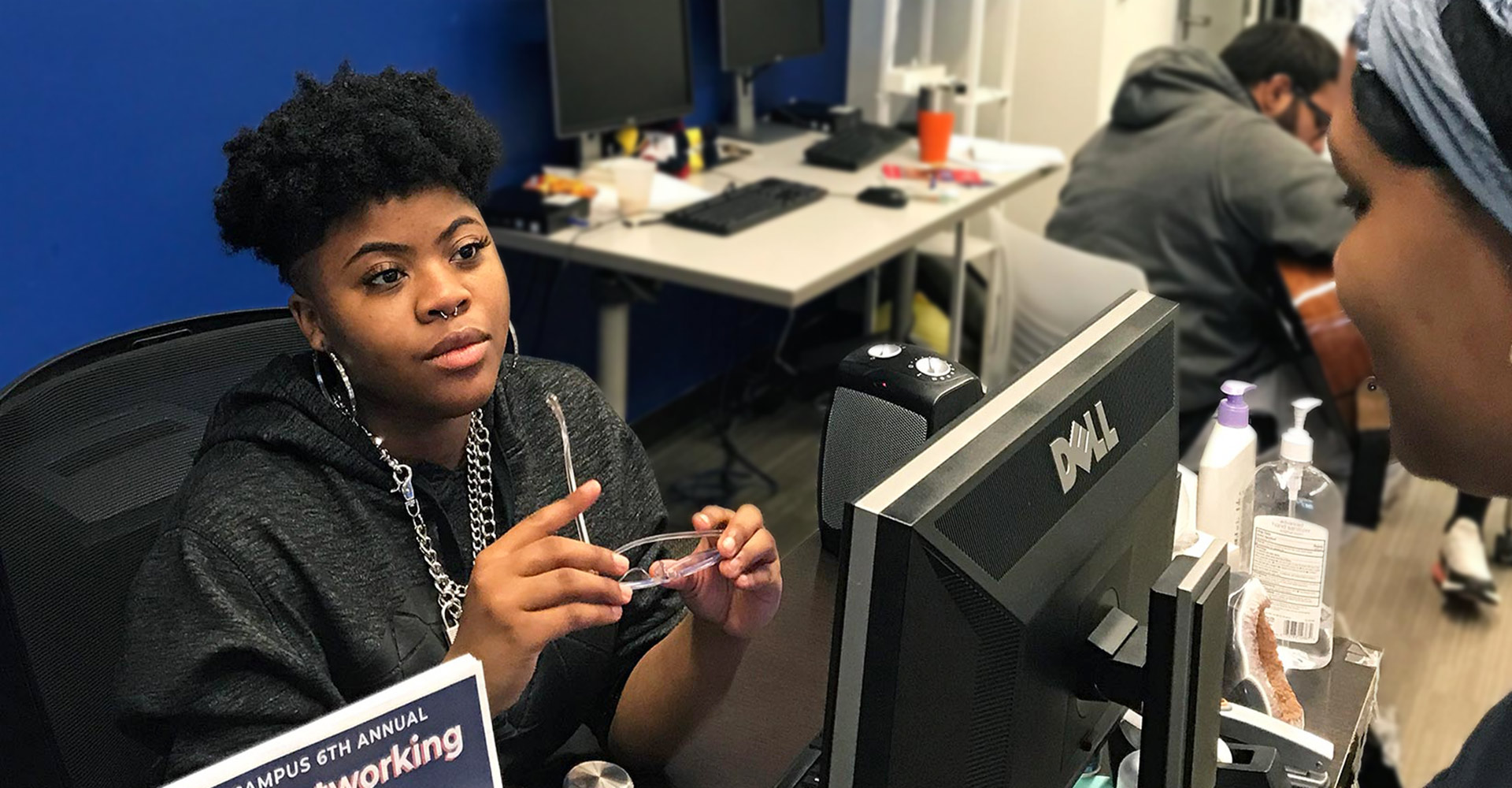

Sauntice Washington is an excellent student. The graduate of Manual High School’s gifted-and-talented program visited universities across the country and knew exactly what she wanted to study in college when she chose Metropolitan State University of Denver.

So she was understandably perplexed when she encountered numerous challenges in her first semester on the Auraria Campus. Selecting the right classes was challenging, as was finding her classrooms. She didn’t even know if she was struggling academically, because she couldn’t figure out how to check her grades.

“I graduated in the top 10 of my high school class with a 4.36 GPA, but I still struggled when I got here,” she said.

Washington is one of 10,581 MSU Denver students who are among the first generation in their family to go to college. Those students – 56% of Roadrunners – are more likely to require additional assistance to navigate life outside the classroom to set them up for academic success.

National data show that the odds are stacked against first-gen students. Six years after entering postsecondary education, 56% of first-gen students have not earned a credential of any sort, compared with 40% of continuing-generation students, according to research from the Center for First-Generation Student Success. The center also reports a staggering financial disadvantage for first-gen students: The median parental income of first-gen students ($41,000) is less than half of the median parental income for continuing-generation students ($90,000).

That’s the reason students such as Washington are taking part in First-Gen Friday at the Capitol this week. Scores of students from MSU Denver, Adams State University and Colorado Mesa University will visit the Colorado state Capitol to talk with legislators about the importance of supporting first-gen students.

|

|

Rep. Leslie Herod, D-Denver; Rep. Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez, D-Denver; and Sen. Dominick Moreno, D-District 21, are sponsoring a tribute to first-gen students that will be read on the House and Senate floors Friday, recognizing the increased time and resources needed to mentor first-gen students and voicing a need to prioritize funding designed to support them.

Students whose parents don’t have a bachelor’s degree are enrolling in increasing numbers at Colorado colleges and universities, but those students are often underserved, according to the Colorado Commission on Higher Education’s Master Plan.

“The students we must focus on to increase attainment – whether they are first-generation, low-income, minority, adult or from other underserved populations – are those most likely to come from backgrounds where they lack traditional support systems and thus require increased services to succeed,” the plan says.

Washington is used to providing the support – she says she has “basically raised” her six siblings as the oldest of the bunch. As the first in her family to go to college, she talks to her brothers and sisters about all the ins and outs of going to school such as financial aid and homework. At age 18, Washington is teaching her 15-year-old sister – who has already graduated from high school – about how to prepare taxes.

She hopes to provide her siblings and future generations of their family with a better life while helping others, too. Washington is studying construction-project management and works at the Center for Multicultural Engagement and Inclusion on campus. Her career goal is to build low-income housing and participate in advocacy work.

“We are actually changing what I like to call ‘generational trauma.’ Our past families haven’t done so well in life, and me and my sister want to set a different tone. We want our children to be born in a stable society instead of what we were born into. A lot has happened to us,” she said.

Sakiynah Wise has faced more challenges than most on her path to a degree. In addition to being a first-gen student, Wise is a single mom who was intermittently homeless in her teens and 20s.

“I went to school because I needed a roof over my head and my daughter’s head. I could no longer risk losing my daughter by living in my car,” she said.

As she finishes her final classes before earning a degree in communications design in May, Wise said she wishes she’d known about resources available to her earlier in her college career. Many first-gen students share that feeling – sometimes they just don’t know what they don’t know. Data from the Center for First-Generation Student Success show that first-gen students are less likely to make use of academic advisors, academic-support services, career services or health services than their peers.

“I didn’t know the different programs I could’ve been a part of until last year. I didn’t even categorize myself as a first-generation student, because I really didn’t know that I was,” she said.

Wise was also reluctant to get help at school because she was on government assistance, and with that assistance come strings attached. She’s had to have professors sign forms to prove she goes to class, which she felt could lead to them looking at her differently. And even though she’s had a few anxiety attacks as a student, she was hesitant to go to the Counseling Center because she didn’t want to ask for more help.

“You don’t really want to fill out a form to say, ‘Hey, I need a little help and more time to get this work done,’’” she said. “You don’t want another thing on top of the pile, on top of the list of things that you’re already accommodated for.”

But the reason she has persisted to her final semester of school – across seven years as a part-time student, including a year off after the birth of her second child – is to end a cycle of government dependency and provide for her children long-term.

“What’s been the key through it all is seeing the vision. The vision for me is: I’m no longer going to be in this perpetual state of assistance,” she said. “Not that you should never have to ask for help, but I’ll be the one being able to help rather than the other way.”

First-gen Friday at the Capitol

First-gen Friday at the Capitol