COVID-19 pandemic reveals critical work of medical-laboratory scientists

They’re rarely seen or heard, but their work is critical in the fight against coronavirus. An innovative postdegree program is training a new crop of scientists for the in-demand field.

While the country anxiously follows progress in the development of a COVID-19 vaccine, doctors are relying on 19th-century convalescent-plasma therapy to treat those infected with the virus.

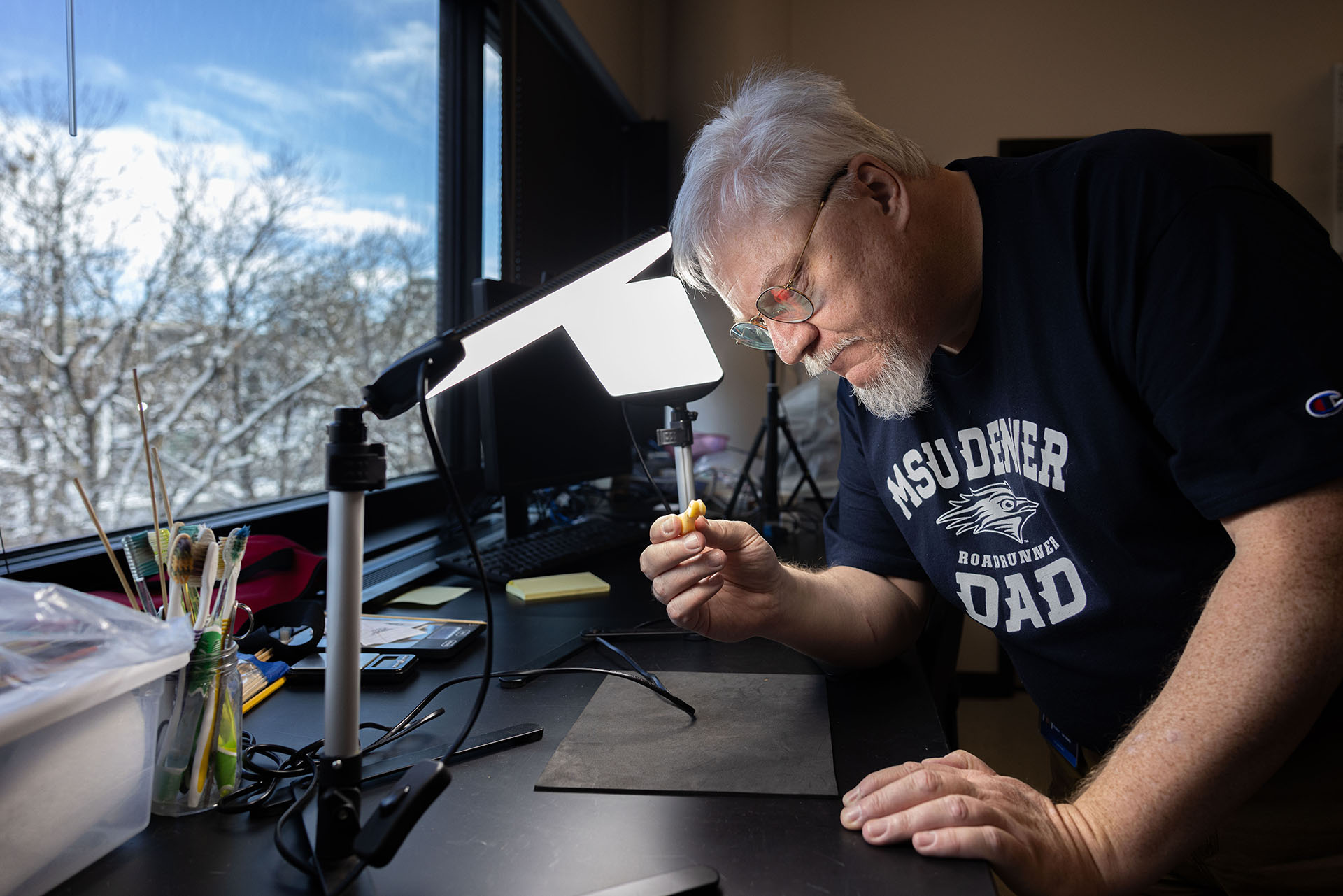

Their reliance on the therapy, first used in the 1890s to treat diphtheria patients, is shining a light on the often-hidden work of medical-laboratory scientists such as Steven King.

King, a student in Metropolitan State University of Denver’s Colorado Center for Medical Laboratory Science, is wrapping up a clinical rotation at Children’s Hospital Colorado on the Anschutz Medical Campus. He’s focused on blood banking – making sure that blood products such as red blood cells, cryoprecipitate, platelets and COVID-19 convalescent plasma are compatible for a patient. The hospital will hire him full time for a lab position after he completes the postbaccalaureate program.

When a person is infected by and recovers from the novel coronavirus, their blood is rich with antibodies that their immune system produced to help them fight the virus off, King said. Without a vaccine, doctors are relying on preventive treatments. One of these infuses antibody-rich blood plasma processed by medical-laboratory scientists into infected patients who may not yet have produced virus-fighting antibodies.

“It has been quite a unique experience and opportunity to be doing our rotations at a time like this during a pandemic,” King said. “It’s an important thing that we’re doing, and it’s been quite the learning experience seeing this side of it.”

MSU Denver’s one-year CCMLS program prepares students for professional certification in medical-laboratory science through postbaccalaureate study in a teaching facility and lab in Aurora. The lab is one of the University’s Innovative and Lifelong Learning programs. Students spend six months in lecture and laboratory classes before beginning clinical-rotation coursework in more than 30 affiliate labs throughout Colorado. That clinical coursework provides critical experience in blood banking, clinical chemistry, hematology, immunology and microbiology. After completing the program, students take a national-certification American Society for Clinical Pathology exam to practice as a medical-laboratory scientist.

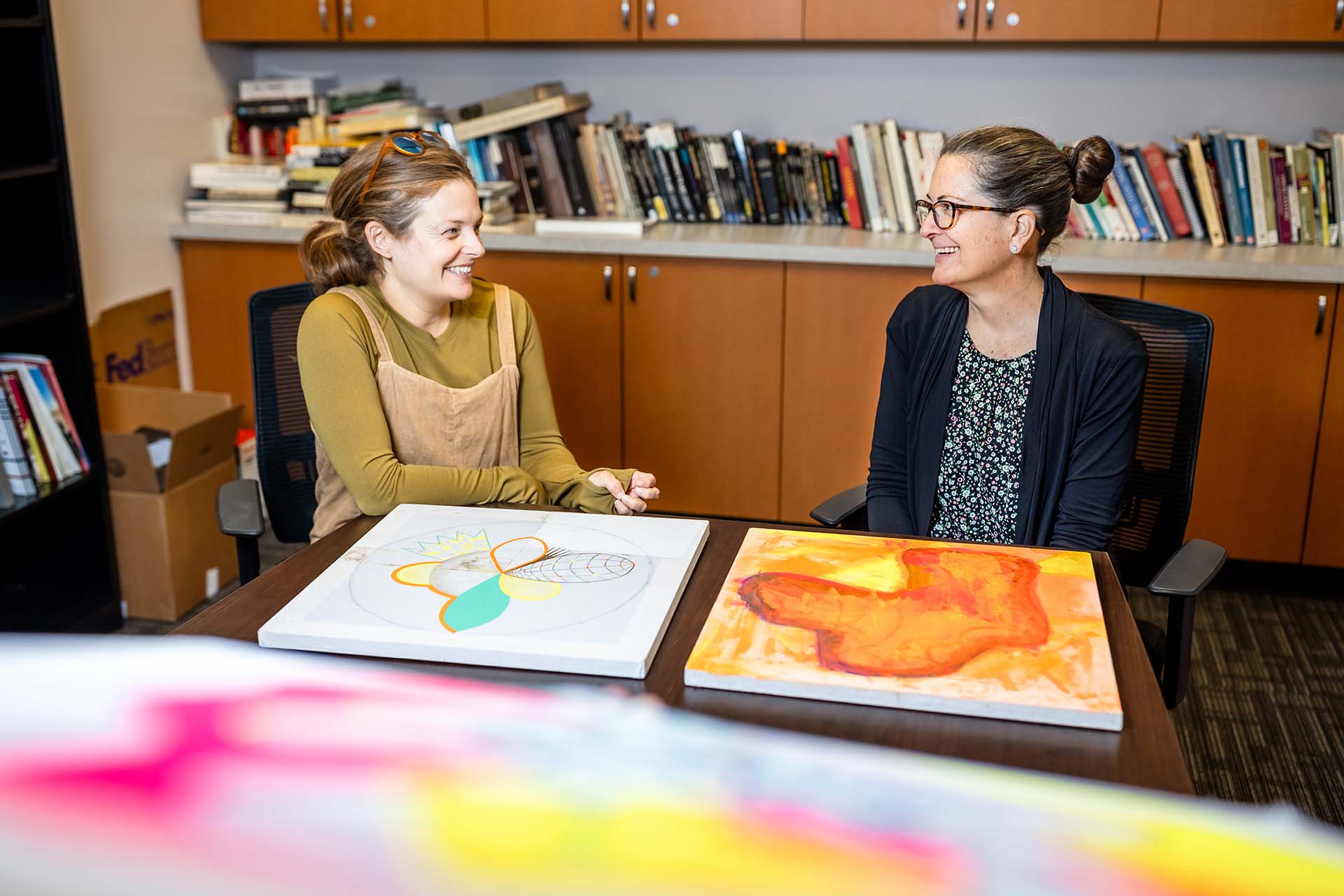

Medical-laboratory scientists work behind closed doors in facilities rarely seen by the public, said Karen Myers, CCMLS director. But as Colorado and the country fight the spread of coronavirus and strive to find treatments for those infected, the medical laboratory is now a front-line position.

“If you ask a man on the street, they don’t know who we are,” Myers said. “That’s because we’re scientists and we’re kind of quiet.”

These scientists are generating analytical data and COVID-19 test results while also overseeing test selection, validating test methods when assays are first brought into a laboratory, maintaining instrumentation and quality assurance and, like King, banking valuable COVID-19 convalescent plasma.

“We don’t get much public credit, and what we do is behind the scenes,” he said. “We are the science behind the medicine.”

Learning in a pandemic

When students such as King began their clinical rotations in January, coronavirus was just beginning to emerge in Wuhan, China. But as the U.S. witnessed its first cases of COVID-19 caused by community spread in late February and early March, Myers told her 30 students to follow all of the scientific developments.

“(The pandemic) is something that doesn’t occur very often, and (students) are on the front end of watching how a disease process develops, how (the disease) is treated and how the human body reacts to it,” she said.

While experts clamor for more coronavirus testing in Colorado and the country, no one talks about the medical-laboratory scientists who are responsible for setting up testing and assuring the quality of testing once it is established in clinical laboratories, Myers said. In fact, the field of medical-laboratory science is experiencing shortages. The need for more graduates is expected to grow as new methodologies, specifically in molecular diagnostics, promise more analytical techniques that will support not only COVID-19 but all patient diagnosis and treatment.

Now, medical-laboratory scientists are having a huge impact during the pandemic. And because the need for their expertise is so in-demand, MSU Denver students enrolled in the medical-laboratory science program are also now working on the front lines of COVID-19 fight.

“Our students are very, very good at what they do. They have a rigorous curriculum, and they are well-prepared and really responsive,” said Myers. “We have had nice feedback, and we are really proud of them. As health care professionals, (medical-laboratory scientists) are always very happy that we can help patients.”

Roadrunners on the front lines

MSU Denver CCMLS graduate Spencer Laidig was a microbiology major when he enrolled in the program, which he said united his passions for science and helping others.

Today, he’s working in the molecular-diagnostics laboratory at UCHealth Anschutz, where he analyzes COVID-19 tests. The lab began preparing for the pandemic in February, when the first American coronavirus cases surfaced, he said.

“There was no form of testing, so we didn’t know how we would test for coronavirus,” he said. “We just knew we would have to test for respiratory viruses.”

As February rolled into March, the UCHealth Anschutz molecular-diagnostics laboratory began to conduct COVID-19 tests while still working through flu season. Now, the lab is prepping for even more work as Colorado slowly reopens under Gov. Jared Polis’ Safer at Home guidelines.

“Our daily lives got upended,” Laidig said. “There are people coming in at 3 in the morning just to get started, and people don’t even leave until 1 in the morning.”

The CCMLS program helped him prepare for his job because it taught him to be aware, think critically and be cognizant of what is going on around him, he said.

“There is a lot to be stressed about in this pandemic. People are dying, and (patients) need to know (test results),” Laidig said. “You have that in the back of your mind when you’re running tests, but you know you are running them efficiently. Even though these are samples, there are live, real people behind them, and it’s crucial we do it to the best of our ability.”